Żydzi

Jahwe/” lub „czciciele /Jahwe/” z hebr. Jehudim, יהודים, jid. Jidn, ייִדן, ladino ג׳ודיוס Djudios) – naród semicki zamieszkujący w starożytności Palestynę (określany wtedy jako Hebrajczycy albo Izraelici), posługujący się wówczas językiem hebrajskim, a w średniowieczu i czasach nowożytnych mieszkający w diasporze na całym świecie i posługujący się wieloma różnymi językami. Żydzi nie stanowią jednolitej grupy religijnej i etnicznej. Dla żydów ortodoksyjnych Żydem jest tylko osoba, która ma ortodoksyjną matkę lub przeszła konwersję na judaizm. Za Żydów uważa się jednak wiele osób, które nie są żydami ortodoksyjnymi. Kto jest Żydem (hebr.? מיהו יהודי) jest pytaniem, na które nie da się jednoznacznie odpowiedzieć, gdyż może to być identyfikacja kulturowa, etniczna lub religijna. Wiele osób, które uważają się z jakichś powodów za Żydów, nie są uznawane przez inne grupy lub instytucje. Dotyczy to na przykład żydów reformowanych, którzy nawet pomimo etnicznego pochodzenia żydowskiego czasem nie są uznawani przez żydów ortodoksyjnych. Według prawa izraelskiego Żydem jest osoba, która ma ortodoksyjną żydowską matkę, chociaż prawo do obywatelstwa bez oficjalnego uznania takiej osoby za Żyda ma każda osoba, która ma przynajmniej jednego dziadka, który był ortodoksyjnym Żydem.Hebrajczycy wchodzili prawdopodobnie w skład grupy Habiru, którą w II tysiącleciu p.n.e. tworzyły ludy przybyłe do Syropalestyny z obszarów Mezopotamii. Uważa się, iż termin Hebrajczycy pochodzi właśnie od nazwy Habiru[4][5][6].

Nazwa i zapis

Żydzi zamieszkujący Izrael są nazywani Izraelczykami; określenie to jednak oznacza także wszystkich obywateli tego kraju (łącznie z Arabami), a czasem także wszystkich mieszkańców Izraela.Zgodnie z zasadami języka polskiego, w którym nazwy narodowości zapisywane są wielką literą, a nazwy wyznawców poszczególnych religii – małą, członków narodu żydowskiego, niezależnie od ich wyznania, nazywa się Żydami, natomiast wyznawców judaizmu – żydami[7]. Istnieją zatem Żydzi niebędący żydami ze względów religijnych.

Źródłosłów

Określenie Żyd, Żydzi pochodzi od słów Juda, Judejczyk – imienia jednego z 12 synów biblijnego patriarchy Jakuba oraz późniejszej nazwy jednego z 12 pokoleń Izraela. Plemiona Judy oraz Symeona zamieszkały w południowej części Palestyny, gdzie też znajdowała się Jerozolima, późniejsza stolica całego Izraela, a następnie, po podziale państwa Salomona, Królestwa Judy. Judejczycy uważali się za bardziej godnych potomków Izraela, gdyż posiadali starożytną stolicę Dawida, świątynię Jahwe oraz w większym stopniu niż ich pobratymcy z północy zachowywali przepisy prawa mojżeszowego. Pod koniec VIII wieku p.n.e. północne Królestwo Izraela zostało rozbite przez Asyryjczyków, którzy także uprowadzili ludność hebrajską sprowadzając na jej miejsce inne narody. Wówczas Judejczycy stali się jedynym pokoleniem Izraela zamieszkującym tereny Ziemi Obiecanej oraz jedynymi Izraelitami, którzy posiadali własne państwo. Od tego momentu pozostałe pokolenia Izraela znajdujące się w diasporze są już rzadko wspominane przez Stary Testament, zaś określenie Judejczyk zaczyna być tożsame ze słowem Izraelita, Hebrajczyk. Także w VIII wieku przed Chrystusem w annałach Tiglat-Pilesera III pojawiają się najstarsze wzmianki o Judzie i rządzących nim królach. O królestwie Judy mówią także dokumenty Sanheriba, Asarhaddona, Assurbanipala oraz Nabuchodonozora II.Pod koniec VII wieku p.n.e. Nabuchodonozor II rozpoczął przesiedlenia ludności judejskiej na tereny Babilonu, zaś w roku 587 p.n.e. został zmuszony do zburzenia Jerozolimy, świątyni i uprowadzenie pozostałych Judejczyków. To właśnie w okresie niewoli babilońskiej termin Judejczyk, Żyd stał się tożsamym ze słowem Izraelita, Hebrajczyk, tak iż mianem Żydów zaczęto określać wszystkie 12 pokoleń, a nie tylko samych Judejczyków. Trend ten można zaobserwować w Starym Testamencie, gdzie słowa Judejczyk i Judejczycy zastępują słowa Izraelici w księgach spisanych po upadku Królestwa Judy. Słowo jehudi יהודי (Judejczyk = Żyd) występuje sporadycznie jeszcze przed niewolą babilońską (2 Królewska 16,6; 25,25; Jeremiasza 32,12; 34,9; 36,14.21.23 38:19), lecz w księgach Nehemiasza i Estery pojawia się aż 61 razy, kilkakrotnie używa go Jeremiasz po upadku Jerozolimy, prorok Zachariasz posługuje się nim określając Izraelitę (8,23). Słowo jehudai יהודאי (Judejczycy = Żydzi) pojawia się dopiero w księdze Daniela (3,8.12) i jest wielokrotnie użyte w księdze Ezdrasza (4,12.23; 5,1.5; 6,7.8.14).

W Nowym Testamencie wszyscy Izraelici często określani są mianem Judejczyków (Żydów), pomimo iż wielu nie pochodziło z plemienia Judy. Apostoł Paweł pochodzący z pokolenia Beniamina (Filipian 3,5) nazywał siebie Judejczykiem, czyli Żydem (Dzieje Apost. 21,39; 22,3; Galacjan 2,15), co wskazuje na fakt, iż już w I wieku n.e. słowo Judejczyk było przez samych Izraelitów używane jako określenie Hebrajczyka.

Wszystkie imiona, które biblijny Jakub-Izrael nadawał swoim 12 synom, posiadały duchowe znaczenie, co dotyczy także imienia J(eh)uda. Z języka hebrajskiego tłumaczy się je jako chwała, wychwalony, wysławiony (w odniesieniu do Boga Jahwe). Żyd (Judejczyk) oznacza więc czciciela lub chwalcę Boga Jahwe i takie tłumaczenie imienia potwierdza opis z Księgi Rodzaju 29,35.

Antropologia fizyczna

W XIX i pierwszej połowie XX wieku toczono dyskusje na temat struktury antropologicznej Żydów. Wyrażano różne stanowiska – od istnienia odrębnej rasy żydowskiej do antropologicznego podobieństwa z ludnością danego kraju. W okresie międzywojennym problem ten poddała analizie lwowska szkoła antropologiczna gł. poprzez badania Salomona Czortkowera i syntezę J. Czekanowskiego. Obydwa powyższe skrajne stanowiska zostały odrzucone i wśród Żydów wyróżniono trzy formacje antropologiczne: orientalną, kaukaską i środkowoeuropejską. W orientalnej wyodrębniono dwa odłamy: Sefardim jerozolimscy (wraz ze zbliżonymi do nich Żydami syryjskimi, mezopotamskimi i kurdystańskimi) będącymi szczątkiem formacji archaicznej z terenu Palestyny oraz Żydzi z Jemenu i Egiptu (z domieszką rasy czarnej). Formacja środkowoeuropejska charakteryzowała się wedle tej teorii silnym występowaniem cech typowych dla ludności tej części Europy. Formacja kaukaska wykazywała silne związki z ludami kaukaskimi i perskimi. Według J.Czekanowskiego różnice pomiędzy formacjami antropologicznymi Żydów w różnych regionach były skutkiem wchłonięcia przez ludność żydowską elementów ludności autochtonicznej jeszcze przed wyizolowaniem Żydów w średniowiecznych gettach[8]. Współcześnie odchodzi się od podobnych teorii, jako potencjalnie rasistowskich[9].Najstarsze dzieje Żydów

Po śmierci Salomona doszło do podziału państwa na dwa królestwa: Judę ze stolicą w Jerozolimie i Izrael ze stolicą w Samarii. Królestwa te istniały równolegle, aż do podbicia Izraela przez Asyrię. W VI w. p.n.e. Judę zdobyła Babilonia, a Żydzi zostali uprowadzeni w tzw. niewolę babilońską. To wydarzenie zapoczątkowało rozproszenie – żydowską diasporę. Do Judei wróciła bowiem tylko niewielka część wysiedlonych Żydów, i to dopiero za króla Persji Cyrusa II Wielkiego. Reszta pozostała nad Eufratem, tworząc świetnie prosperującą społeczność.

Wielu uczonych uważa, iż nazwa Hebrajczycy pochodzi od terminu Habiru, starożytnego określenia wędrownych plemion semickich przybyłych do Palestyny zza Eufratu, którzy za czasów Amenhotepa IV spustoszyli miasta-państwa Kanaanu. Najstarszą inskrypcją wymieniającą Izrael wśród narodów Kanaanu jest Stela Merneptaha z XIII wieku p.n.e., zaś pierwsze wzmianki o Izraelu jako państwie znajdują się na Steli Meszy z IX wieku p.n.e.

Żydzi w diasporze

Dzieci żydowskie z nauczycielem w Samarkandzie około roku 1911, fot. Prokudin-Gorski

Ludność żydowska w diasporze w wyniku rozproszenia w różnych warunkach życiowych i w różnym otoczeniu rozpadła się na kilka odrębnych grup etniczno-kultowych: Aszkenazyjczyków, Sefardyjczyków, Żydów orientalnych, posługujących się różnymi językami (jidysz, dialekty judeo-romańskie). Pomimo rozproszenia, Żydzi zachowali swoją kulturę przez blisko dwa tysiące lat. Elementem łączącym Żydów rozsianych po całym świecie był judaizm – monoteistyczna religia, której przykazania obejmowały nie tylko kwestie wiary, lecz szczegółowo regulowały wszystkie aspekty życia codziennego. Judaizm stanowił podstawę świadomości narodowej Żydów i stanowił wyznacznik żydowskości – w przypadku Żydów wyznanie ściśle pokryło się z narodowością.

Żydzi rozproszyli się po całym znanym wówczas świecie. Kolonie żydowskie powstały w całej Europie, w nieprzyjaznym Rzymianom imperium perskim, na Kaukazie, w zachodnich Chinach, w Etiopii, w Arabii, w Afryce – zarówno w prowincjach rzymskich, jak i na jej wschodnim wybrzeżu. Nauki Mahometa wykazują wpływ teologii żydowskiej. Był to również okres żydowskiego prozelityzmu – najbardziej znanym jego przykładem jest Kaganat Chazarski. Istniejące od VI do X wieku na stepach między Morzem Czarnym a Morzem Kaspijskim państwo Chazarów, ludu pochodzenia tureckiego, przyjęło judaizm jako wyznanie państwowe.

Niektórzy autorzy, na przykład Artur Koestler, popierali kontrowersyjną tezę według której po upadku państwa Chazarów uchodźcy chazarscy, tzw. później żydzi chazarscy, przybyli do Europy i dali początek Żydom aszkenazyjskim. Inni, jak profesor Uniwersytetu w Tel-Awiwie Szlomo Sanda negują w ogóle narodową odrębność Żydów wskazując na liczne różnice antropologiczne i kulturowe pomiędzy poszczególnymi grupami[10].

Diaspora europejska

W średniowieczu najliczniejsza była diaspora europejska. Głównymi ośrodkami osadnictwa żydowskiego były Nadrenia, w której duże skupiska Żydów pojawiły się w okresie rządów Karola Wielkiego (stąd aszkenazim, hebr. „Niemcy”) oraz Andaluzja – muzułmańska Hiszpania (stąd sefardim, hebr. „Hiszpanie”), gdzie warunki dla Żydów do przybycia Almorawidów w 1086 r. były tak korzystne, że często sprawowali najważniejsze funkcje państwowe. Diaspora andaluzyjska uległa częściowo rozproszeniu (po reszcie Europy, Afryce północnej i po Bliskim Wschodzie) po wypędzeniu Żydów z Hiszpanii i Portugalii w latach 1492-1497, a częściowo uległa asymilacji. Natomiast w Polsce Żydzi masowo osiedlali się od XIII wieku. W połowie XVI wieku na ziemiach polskich żyło już ok. 80 proc. ogółu Żydów świata[11].W krajach feudalnej Europy chrześcijańskiej Żydzi stanowili odrębną grupę ludności, w istocie odrębny stan – rządzili się własnymi prawami, mieli własne sądy, władze samorządowe, zwykle cieszyli się ochroną panującego, ponieważ jako „słudzy Skarbu” (servici camerae) zapewniali mu dopływ gotówki z podatków. Żydzi skupiali się w miastach, gdzie osiedlali się w gettach – odrębnych dzielnicach, nieraz z własnymi murami i władzami. Należy podkreślić, że getta stanowiły skupiska dobrowolne i otwarte, podobnie, jak skupiska innych grup narodowościowych (np. Ormian).

W diasporze częste były akty wrogości wobec Żydów, szczególnie w okresach klęsk żywiołowych, za które ich winiono. Przybierały one zwykle formę pogromów – ruchawek tłumu, mordującego Żydów i rabującego dzielnice żydowskie. Ponadto oskarżano Żydów o mordy rytualne (sprawa Szymona z Trydentu) i profanacje. Aż do czasów reżimu Hitlera w Europie nie zdarzały się natomiast prześladowania w formie represyjnego ustawodawstwa – bo nie należy za takie uważać systemu feudalnego prawa, w którym każda grupa ludności („nacja”, „stan”) miała właściwe dla siebie przywileje i ograniczenia. Wyjątkiem była Rosja, gdzie carowie nakładali na Żydów dalej idące ograniczenia i dopuszczali do pogromów. Do XX wieku ogólne nastawienie chrześcijan do Żydów, których wciąż uważano za „nieprzyjaciół Chrystusa”, było nieprzyjazne, a niekiedy otwarcie wrogie.

Niedługo po odkryciu Nowego Świata zaczęło się osadnictwo żydowskie w Ameryce.

W drugiej połowie XIX i XX wieku wśród Żydów europejskich powstały dwie przeciwstawne koncepcje: dążenie do asymilacji Żydów w miejscu ich zamieszkania oraz odrodzenia więzi narodowych i utworzenia własnego państwa (syjonizm). Narastające nastroje antysemickie w Europie oraz wzrastająca popularność ruchu syjonistycznego przyczyniły się do zapoczątkowania, a potem do emigracji kolejnych grup Żydów do Palestyny.

W XIX i XX wieku dokonały się dwie duże migracje Żydów – do USA i do Izraela.

Diaspory według wielkości

Stany Zjednoczone są dziś siedzibą pierwszej co do wielkości diaspory żydowskiej; wedle badań przeprowadzonych w 2005 roku liczba Żydów w poszczególnych krajach wynosiła (wielkości przybliżone):- Stany Zjednoczone: > 6 155 tys. (ponad połowa nie należy do żadnej wspólnoty religijnej)

- Rosja: 800 tys.

- Francja: 606 561

- Ukraina: 500 tys.

- Kanada: 394 tys.

- Argentyna: 182 300

- Wielka Brytania: > 300 tys.

- Niemcy: > 220 tys.

- Brazylia: 130 tys.

- Australia: 120 tys.

- Południowa Afryka: 106 tys.

- Belgia: 52 tys.

- Meksyk: 50 tys.

- Włochy: 45 tys.

- Iran: 40 tys.

- Holandia: 40 tys.

- Turcja: 30 tys.

- Polska: 1,5 tys.

II wojna światowa

Żyd w podeszłym wieku w getcie warszawskim

Powstanie współczesnego Izraela

Obecnie Izrael zamieszkuje ponad 5,5 mln Żydów spośród żyjących na świecie około 17 mln. Wielu Żydów mieszkających w Izraelu czy USA nie ma według prawa tego kraju oficjalnego statusu Żyda.

***

Juden

Der Begriff „jüdisches Volk“

Unter dem „jüdischen Volk“ werden sowohl das historische Volk der Israeliten als auch, dem jüdischen Selbstverständnis gemäß, alle Juden verstanden, die nach der Tora von den Erzvätern Abraham, Isaak und Jakob abstammen. Deren Verheißungsgeschichte hat nach dem ersten Buch Mose[1] einen alle Völker segnenden, sie einbeziehenden Charakter: Wer von einer jüdischen Mutter geboren ist, gilt im Talmud daher ebenso als Jude wie jemand, der zu diesem Glauben übergetreten ist, unabhängig von seiner Herkunft. Der Begriff des jüdischen Volkes im zweiten Sinne bezeichnet nicht ein ethnisch einheitliches Nationalvolk mit geschlossenem Siedlungsraum, einer gemeinsamen Geschichte, Sprache und Kultur, sondern eines, das zur jüdischen Diaspora zerfiel. Der Begriff Volk wäre nach der zweiten Definition in seiner alten Bedeutung zu verstehen, nämlich im Sinne von Leuten (vgl. das englische Wort people ohne Artikel), die durch das Attribut jüdisch im religiösen Sinne hinreichend bestimmt sind.Der Bezug auf die gemeinsame Herkunft verbindet religiöse und säkulare Juden: „Von Zugehörigkeit zum Volk Israel […] kann man jedoch auch sprechen, wenn ein Individuum kulturell oder religiös von der religiös-kulturellen Wirklichkeit der Geschichte Israels in wesentlichen Bereichen seiner Persönlichkeit als geschichtliches Wesen faktisch geprägt ist und das positiv akzeptiert.“[2]

Das deutsche Wort „Jude“ kommt vom hebräischen jehudi יְהוּדִי, was so viel wie „Bewohner des Landes Jehūdāh“ bedeutet. Das Wort kam trotz der vorherigen Existenz des israelitischen Südreiches Juda erst in persischer Zeit in Gebrauch – zur Bezeichnung der Bewohner der damaligen persischen Provinz Jehūdāh.

Entstehung des Judentums

Abraham und Isaak (Gemälde des Malers van Dyck)

Als Stifter der jüdischen Religion gilt Mose. „Mosaische Religion“ ist ein heute kaum mehr verwendetes Synonym für die jüdische Religion. Moses ist im Judentum der höchste Prophet aller Zeiten, der Gott so nah kam, wie sonst kein Mensch vorher oder seitdem. Historische Belege für die Existenz Mose fehlen jedoch. In der Bibel führt Mose den Auszug des hebräischen Volkes aus Ägypten an. Wann und ob dieser historisch stattgefunden hat, ist jedoch ebenfalls unklar. Traditionell gilt Mose zudem als Verfasser der nach ihm benannten „Fünf Bücher Mose“ (in der jüdischen Religion umgangssprachlich „Tora“ genannt), die die Basis des jüdischen Glaubens bilden. Diese Auffassung wird heute jedoch außerhalb des Orthodoxen Judentums (sofern dort überhaupt mit der Historizität des Mose gerechnet wird) kaum mehr vertreten.

Als eigentlicher Begründer des heutigen Judentums gilt Esra (um 440 v. Chr.). Esra war in der Zeit des Babylonischen Exils Hohepriester und durfte mit seinem verschleppten israelischen Volk, das aus vermutlich etwa 20.000 Menschen bestand, auf Erlass des Perserkönigs Artaxerxes I. zurück nach Jerusalem. Dort ordnete er Tempeldienst und Priestertum neu und ließ Ehen von Juden mit heidnischen Frauen scheiden. Die religiöse Identität ist seitdem für das Judentum von ähnlicher Bedeutung wie die der Herkunft.

Geschichte der Juden

Die Geschichte der Juden verlief unterschiedlich, je nach Land und Epoche. Sie ist sowohl von Unterdrückung, Verfolgung und Vertreibung als auch von Toleranz, friedlichem Miteinander und Gleichberechtigung geprägt. Sie beinhaltet die Geschichte der Juden in der Diaspora und die Gründung des Staates Israel. Als Ursache für die Entstehung der Diaspora werden politische, religiöse oder wirtschaftliche Aspekte angeführt. Die Diaspora entwickelte sich in bedeutenden Zentren jüdischer Gemeinden in Ägypten, in Kyrenaika, Nordafrika, Zypern, Syrien, Kleinasien und schließlich in Griechenland und Rom, bis die Vertreibung beziehungsweise Auswanderung sich weltweit ausbreitete. Weltweit leben 8,1 Millionen Juden in der Diaspora.Begriff in der jüdischen Tradition

Laut Halacha, den jüdischen Religionsvorschriften, gilt eine Person als jüdisch, wenn sie eine jüdische Mutter hat, unabhängig davon, ob, oder wie sehr sie die jüdischen Glaubensvorschriften befolgt oder nicht. Dabei ist es Bedingung, dass die Mutter bei der Empfängnis Jüdin nach der Halacha sein muss. Außerdem gilt als Jude, wer formell die Konversion zum Judentum (Gijur genannt) vollzogen hat. Einfacher Glaube an die jüdische Religion reicht nicht aus.Das Prinzip der Halacha wird im Talmud auf die Tora zurückgeführt. Dadurch entwickelte sich eine Kultur, die über lange Zeit stabil blieb und den Juden eine eigene Identität bewahrte, obwohl sie über fast zwei Jahrtausende hinweg keinen eigenen Staat, vor allem kein eigenes Staatsgebiet, hatten. Ihre Heimat war und ist der ewige Bund Gottes mit Abraham und das an Moses und die anderen Propheten verkündete ewige Gesetz Gottes. Eine gleiche Phase der Diaspora (Zerstreuung) hatte das Volk Israel bereits in der babylonischen Verbannung überstanden. Heimgekehrt nach Jerusalem, begrenzten die Kinder Israels ihr Volk erneut auf die leiblichen Nachfahren Abrahams, Isaaks und Jakobs (Israels). Damals erreichte der Prophet Esra, dass Juden, die sich mit nichtjüdischen Frauen verbunden hatten, diese und die mit ihnen gezeugten Mischlingskinder verstoßen mussten.

Neubewertungen

Im Zeitalter der Aufklärung kam es innerhalb des Judentums zur Diskussion über den Sinn mancher Gesetze der Tora. Das Reformjudentum postulierte seit dem 19. Jahrhundert eine Unterscheidung zwischen universalen religiösen Werten und historisch bedingten religiösen Ritualgesetzen, deren Anpassung an die Gegenwart gefordert wurde. In West- und Mitteleuropa waren die Assimilationsbestrebungen weitaus stärker als in Osteuropa, wo die Juden vielerorts bis ins 20. Jahrhundert als Nationalität galten. Liberale jüdische Gemeinden – z. B. in den USA oder Großbritannien – vertreten heute eine weniger strenge Fassung des Begriffs „Jude“.Innerhalb des Judentums

Die Menora, Symbol jüdischen Glaubens

Orthodoxes und konservatives Judentum

Der orthodoxen Interpretation der Halacha entsprechend, ist nur das leibliche Kind einer jüdischen Mutter als jüdisch zu bestimmen. Ein Kind mit einem jüdischen Vater und einer nichtjüdischen Mutter wird als nichtjüdisch betrachtet. Obwohl die Konversion eines Säuglings unter bestimmten Umständen wie etwa bei Adoptivkindern oder bei Kindern konvertierender Eltern in Betracht gezogen werden kann, werden konvertierte Kinder beim Eintritt in den religiösen Erwachsenenstatus, der bei Mädchen im Alter von 12 Jahren, bei Jungen im Alter von 13 Jahren erreicht wird, typischerweise befragt, ob sie jüdisch bleiben wollen. Dieser Standard gilt im konservativen und im orthodoxen Judentum.Liberales und Reformjudentum

Jüdische Glaubensgemeinschaften, die die orthodoxen Auslegungen des jüdischen Gesetzes nicht als bindend anerkennen, haben andere Standards. Das amerikanische Reformjudentum und das Liberale Judentum in Großbritannien erkennen ein Kind mit nur einem jüdischen Elternteil – Mutter oder Vater – als jüdisch an, wenn dieses Kind den Standards dieser Gemeinschaft entsprechend als Jude aufgezogen wird. Für ernsthaft gemeinte Konversion sind alle heute weitverbreiteten Formen des Judentums offen. Obwohl es um die Konversion zum Judentum eine Kontroverse gibt, akzeptieren alle religiösen Bewegungen ohne Einschränkung Konvertiten, die sie selbst aufgenommen haben.Diese Abweichung von der traditionellen Sichtweise hat zu starken Spannungen mit traditionellen konservativen und orthodoxen Juden geführt.

Die Frage, ob eine Person Jude ist oder nicht, hat weitreichende religiöse Bedeutung. Einige orthodoxe Autoritäten erklären eine jüdische Ehe nur als gültig, wenn sie zwischen zwei Juden geschlossen wird. Ein öffentlicher Gemeindegottesdienst kann nur abgehalten werden, wenn mindestens zehn jüdische Beter (Minjan) teilnehmen.

Weltliches Judentum

Die Mitglieder der meisten weltlichen jüdischen Gemeinschaften akzeptieren jeden Menschen als Juden, der sich als solcher erklärt, es sei denn, es gibt Grund zur Annahme, dass diese Person damit eine Täuschung begeht. Manche Mitglieder des Reformjudentums teilen diesen Standpunkt.Im Staat Israel

Das Gebäude der Knesset, Südseite

Antijudaismus und Antisemitismus

Der wandernde Ewige Jude,

farbiger Holzschnitt von S. C. Dumont, 1852 (nach Gustave Doré).

Reproduktion als nationalsozialistisches Propoganda-Plakat (vor 1937) in

einer Ausstellung in Yad Vashem, 2007

So konnte die mittelalterliche Beschränkung der Juden auf wenige erlaubte Berufe dazu führen, dass der Begriff des Juden noch in der 4. Auflage des Concise Oxford Dictionary von 1950 in seiner übertragenen Bedeutung als „maßloser Wucherer“ definiert wird.

Der Antisemitismus definierte das Judesein ethnisch und rassistisch, um konvertierte Juden weiterhin als Juden mit angeblich unveränderlichen, ererbten negativen Charaktereigenschaften ausgrenzen zu können. Sie konnten im Deutschen Kaiserreich trotz rechtlicher Gleichstellung weder durch Verzicht auf ihre Religionsausübung noch durch Heirat mit Andersgläubigen oder Konversion zum Christentum volle gesellschaftliche Anerkennung, Bildungs- und Aufstiegschancen erreichen. In der völkischen Bewegung wurde diese Ablehnung verschärft und die Vertreibung oder Ausweisung aller von Juden abstammenden Personen gefordert. Der Nationalsozialismus übernahm die Vertreibung aller jüdischstämmigen und mit Juden verheirateten „Mischlinge“ als politisches Ziel und führte 1935 eine entsprechende Gesetzgebung ein: die Nürnberger Gesetze. Diese wurden, ungeachtet des Glaubensbekenntnisses, auf alle Personen angewandt, die mindestens einen jüdischen Großelternteil (männlich oder weiblich) hatten; wobei diejenigen mit väterlicher/großväterlicher Abstammung wesentlich härter ausgegrenzt wurden und das Jahr 1800 willkürlich festgelegt wurde für den Zeitpunkt der Konversion. Den betroffenen Menschen in Deutschland wurden damit ihre deutsche Nationalität und Bürgerrechte aberkannt (→ Reichsbürgergesetz – Erste Verordnung vom 14. November 1935). Das NS-Regime benutzte diese rassistische Definition des Judeseins seit Beginn des Zweiten Weltkriegs in den von Deutschland besetzten Gebieten zur Deportation, Ghettoisierung und Ermordung der Juden in der Schoah.

Demografie

Stand 2014 leben weltweit etwa 14,3 Millionen Juden, das entspricht rund 0,2 % der Weltbevölkerung, die meisten in Israel und in den Vereinigten Staaten. Andere Schätzungen sprechen von etwa 15 Millionen Menschen weltweit. In der Diaspora stellen Juden in den USA mit 1,8 % den größten Bevölkerungsanteil, gefolgt von Kanada mit 1,1 % und Frankreich mit 0,7 %. In Deutschland beträgt der Bevölkerungsanteil 0,1 %.Durch verschiedene Emigrations- und Immigrationswellen hat sich die Verteilung der Juden in der Welt seit dem Ausgang des 20. Jahrhunderts verändert. Anfang der 1990er Jahre lebte noch ein Großteil der Juden in der Sowjetunion. Nach ihrer Auflösung wanderten viele Menschen nach Israel, in die Vereinigten Staaten und nach Deutschland aus (siehe auch: Alija).

Folgende Tabelle basiert auf Angaben der Jewish Agency for Israel aus dem Jahr 2014, sofern nicht anders angegeben.[3]

| Land | Juden | Prozent aller Juden |

Prozent der Bevölkerung |

Anmerkungen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.217.400 | 43,62 | 74,0 | ||

| 5.700.000 | 38,83 | 1,8 | Schätzungen: 6,7–6,8 Mio.[4] | |

| 467.500 | 3,27 | 0,7 | Schätzungen: 600.000 | |

| 386.000 | 2,57 | 1,1 | ||

| 290.000 | 2,03 | 0,4 | ||

| 183.000 | 1,28 | 0,2 | ||

| 181.000 | 1,27 | 0,4 | Schätzungen: bis zu 250.000 | |

| 117.500 | 0,82 | 0,1 | Schätzungen: 200.000[5] | |

| 112.800 | 0,79 | 0,5 | ||

| 94.500 | 0,66 | 0,1 | ||

| 69,800 | 0,49 | 0,2 | Schätzungen: 106.000 | |

| 60.000 | 0,42 | 0,2 | ||

| 47.700 | 0,33 | 0,5 | ||

| 40.000 | 0,28 | 0,04 | Schätzungen: 45.000 bis 50.000 | |

| 31.400 | 0,22 | 0,3 | Schätzungen: 30.000 bis 35.000 | |

| 29.400 | 0,20 | 0,05 | Schätzungen: 30.000 bis 35.000 | |

| 28.000 | 0,20 | 0,18 | Schätzungen: 30.000 bis 35.000 | |

| 24.300 | 0,17 | 0,24 | Schätzungen: 30.000 bis 35.000 | |

| 17.700 | 0,14 | 0,21 | offiziell: 17.914[6] | |

| 17.000 | 0,12 | 0,03 | Schätzungen: 23.000 bis 30.000 | |

| 9.300 | 0,06 | 0,03 | Schätzungen: 23.000 bis 30.000 | |

| 9.000 | 0,06 | 0,1 | Schätzungen bis 15.000[7] | |

| 8.800 | 0,06 | 0,01 | ||

| 2,400 | 0,02 | 0,0 | ||

| 2,000 | 0,01 | 0,0 | ||

| 100 | 0,00 | 0,0 | ||

| Welt | 14.310.500 | 100,0 | 0,19 |

Verteilung nach Kontinenten

Die jüdische Bevölkerung verteilt sich wie folgt auf die Kontinente:[8]| Kontinent | Juden | Prozent der Bevölkerung |

|---|---|---|

| Europa | 1.457.920 | 1,96 % |

| Asien + Pazifik | 160.000 | 0,03 % |

| Lateinamerika + Karibik | 429.000 | 0,07 % |

| Nordamerika | 5.927.000 | 1,27 % |

| Naher Osten + Nordafrika | 5.617.000 | 1,65 % |

| Afrika (südlich der Sahara) | 61.000 | 0,01 % |

| Australien | 111.350 | 0,5 % |

| Welt | 13.763.000 | 0,186 % |

***

Jews

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the Jewish people. For their religion, see Judaism.

"Jew" redirects here. For other uses, see Jew (disambiguation).

| Hebrew: יהודים (Yehudim) | |

|---|---|

According to Jewish tradition, Jacob was the father of the tribes of Israel.

|

|

| Total population | |

| 14.7–17.4 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 6,481,182[2] | |

| 5,300,000–6,800,000[3][4] | |

| 467,500[3] | |

| 386,000[3] | |

| 290,000[3] | |

| 183,000[3] | |

| 181,000[3] | |

| 117,500[3] | |

| 112,800[3] | |

| 94,500[3] | |

| 69,800[3] | |

| 60,000[3] | |

| 47,700[3] | |

| 40,000[3] | |

| 29,900[3] | |

| 29,800[3] | |

| 27,600[3] | |

| 18,900[3] | |

| 18,400[3] | |

| 9,900[3] | |

| Rest of the world | 218,100[3] |

| Languages | |

Sacred languages: |

|

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Samaritans,[6] Druze, other Levantines,[6][7][8][9] Arabs,[6][10] Assyrians,[6][9] European peoples[11][12][13] | |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

Jews originated as a national and religious group in the Middle East during the second millennium BCE,[10] in the part of the Levant known as the Land of Israel.[21] The Merneptah Stele appears to confirm the existence of a people of Israel, associated with the god El,[22] somewhere in Canaan as far back as the 13th century BCE (Late Bronze Age).[23][24] The Israelites, as an outgrowth of the Canaanite population,[25] consolidated their hold with the emergence of the Kingdom of Israel, and the Kingdom of Judah. Some consider that these Canaanite sedentary Israelites melded with incoming nomadic groups known as 'Hebrews'.[26] Though few sources in the Bible mention the exilic periods in detail,[27] the experience of diaspora life, from the Ancient Egyptian rule over the Levant, to Assyrian Captivity and Exile, to Babylonian Captivity and Exile, to Seleucid Imperial rule, to the Roman occupation and Exile, and the historical relations between Jews and their homeland thereafter, became a major feature of Jewish history, identity and memory.[28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37]

The worldwide Jewish population reached a peak of 16.7 million prior to World War II,[38] but approximately 6 million Jews were systematically murdered[39][40] during the Holocaust. Since then the population has slowly risen again, and as of 2015 was estimated at 14.3 million by the Berman Jewish DataBank,[3] or less than 0.2% of the total world population (roughly one in every 514 people).[41] According to the report, about 43% of all Jews reside in Israel (6.2 million), and 40% in the United States (5.7 million), with most of the remainder living in Europe (1.4 million) and Canada (0.4 million).[3] These numbers include all those who self-identified as Jews in a socio-demographic study or were identified as such by a respondent in the same household.[42] The exact world Jewish population, however, is difficult to measure. In addition to issues with census methodology, disputes among proponents of halakhic, secular, political, and ancestral identification factors regarding who is a Jew may affect the figure considerably depending on the source.[43] Israel is the only country where Jews form a majority of the population. The modern State of Israel was established as a Jewish state and defines itself as such in its Declaration of Independence and Basic Laws. Its Law of Return grants the right of citizenship to any Jew who requests it.[44]

Despite their small percentage of the world's population, Jews have significantly influenced and contributed to human progress in many fields, including philosophy,[45] ethics,[46] literature, business, fine arts and architecture, religion, music, theatre[47] and cinema, medicine,[48][49] as well as science and technology, both historically and in modern times.

Name and etymology

Main articles: Jew (word) and Ioudaios

The English word Jew continues Middle English Gyw, Iewe. These terms derive from Old French giu, earlier juieu, which had elided (dropped) the letter "d" from the Medieval Latin Iudaeus, which, like the New Testament Greek term Ioudaios, meant both Jews and Judeans / "of Judea".[50]The Greek term was originally a loan from Aramaic Y'hūdāi, corresponding to Hebrew: יְהוּדִי, Yehudi (sg.); יְהוּדִים, Yehudim (pl.), in origin the term for a member of the tribe of Judah or the people of the kingdom of Judah. According to the Hebrew Bible, the name of both the tribe and kingdom derive from Judah, the fourth son of Jacob.[51]

The Hebrew word for Jew, יְהוּדִי ISO 259-3 Yhudi, is pronounced [jehuˈdi], with the stress on the final syllable, in Israeli Hebrew, in its basic form.[52] The Ladino name is ג׳ודיו, Djudio (sg.); ג׳ודיוס, Djudios (pl.); Yiddish: ייִד Yid (sg.); ייִדן, Yidn (pl.).

The etymological equivalent is in use in other languages, e.g., يَهُودِيّ yahūdī (sg.), al-yahūd (pl.), and بَنُو اِسرَائِيل banū isrāʼīl in Arabic, "Jude" in German, "judeu" in Portuguese, "juif" in French, "jøde" in Danish and Norwegian, "judío" in Spanish, "jood" in Dutch, "żyd" in Polish etc., but derivations of the word "Hebrew" are also in use to describe a Jew, e.g., in Italian (Ebreo), in Persian ("Ebri/Ebrani" (Persian: عبری/عبرانی)) and Russian (Еврей, Yevrey).[53] The German word "Jude" is pronounced [ˈjuːdə], the corresponding adjective "jüdisch" [ˈjyːdɪʃ] (Jewish) is the origin of the word "Yiddish".[54] (See Jewish ethnonyms for a full overview.)

According to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, fourth edition (2000):

It is widely recognized that the attributive use of the noun Jew, in phrases such as Jew lawyer or Jew ethics, is both vulgar and highly offensive. In such contexts Jewish is the only acceptable possibility. Some people, however, have become so wary of this construction that they have extended the stigma to any use of Jew as a noun, a practice that carries risks of its own. In a sentence such as There are now several Jews on the council, which is unobjectionable, the substitution of a circumlocution like Jewish people or persons of Jewish background may in itself cause offense for seeming to imply that Jew has a negative connotation when used as a noun.[55]

Origins

See also: Origins of Judaism, Jewish history, Israelites, History of Ancient Israel and Judah, and Canaan

Map of Canaan

According to the Hebrew Bible narrative, Jewish ancestry is traced back to the Biblical patriarchs such as Abraham, his son Isaac, Isaac's son Jacob, and the Biblical matriarchs Sarah, Rebecca, Leah, and Rachel, who lived in Canaan around the 18th century BCE. Jacob and his family migrated to Ancient Egypt after being invited to live with Jacob's son Joseph by the Pharaoh himself. The patriarchs' descendants were later enslaved until the Exodus led by Moses, traditionally dated to the 13th century BCE, after which the Israelites conquered Canaan.[citation needed]

Modern archaeology has largely discarded the historicity of the Patriarchs and of the Exodus story,[57] with it being reframed as constituting the Israelites' inspiring national myth narrative. The Israelites and their culture, according to the modern archaeological account, did not overtake the region by force, but instead branched out of the Canaanite peoples and culture through the development of a distinct monolatristic—and later monotheistic—religion centered on Yahweh,[58][59][60] one of the Ancient Canaanite deities. The growth of Yahweh-centric belief, along with a number of cultic practices, gradually gave rise to a distinct Israelite ethnic group, setting them apart from other Canaanites. The Canaanites themselves are archeologically attested in the Middle Bronze Age,[61] while the Hebrew language is the last extant member of the Canaanite languages. In the Iron Age I period (1200–1000 BCE) Israelite culture was largely Canaanite in nature.[citation needed]

Although the Israelites were divided into Twelve Tribes, the Jews (being one offshoot of the Israelites, another being the Samaritans) are traditionally said to descend mostly from the Israelite tribes of Judah (from where the Jews derive their ethnonym) and Benjamin, and partially from the tribe of Levi, who had together formed the ancient Kingdom of Judah,[62] and the remnants of the northern Kingdom of Israel who migrated to the Kingdom of Judah and assimilated after the 720s BCE, when the Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[63]

Israelites enjoyed political independence twice in ancient history, first during the periods of the Biblical judges followed by the United Monarchy.[disputed ] After the fall of the United Monarchy the land was divided into Israel and Judah. The term Jew originated from the Roman "Judean" and denoted someone from the southern kingdom of Judah.[64] The shift of ethnonym from "Israelites" to "Jews" (inhabitant of Judah), although not contained in the Torah, is made explicit in the Book of Esther (4th century BCE),[65] a book in the Ketuvim, the third section of the Jewish Tanakh. In 587 BCE Nebuchadnezzar II, King of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, besieged Jerusalem, destroyed the First Temple, and deported the most prominent citizens of Judah.[66] In 586 BCE, Judah itself ceased to be an independent kingdom, and its remaining Jews were left stateless. The Babylonian exile ended in 539 BCE when the Achaemenid Empire conquered Babylon and Cyrus the Great allowed the exiled Jews to return to Yehud and rebuild their Temple. The Second Temple was completed in 515 BCE. Yehud province was a peaceful part of the Achaemenid Empire until the fall of the Empire in c. 333 BCE to Alexander the Great. Jews were also politically independent during the Hasmonean dynasty spanning from 140 to 37 BCE and to some degree under the Herodian dynasty from 37 BCE to 6 CE. Since the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, most Jews have lived in diaspora.[67] As an ethnic minority in every country in which they live (except Israel), they have frequently experienced persecution throughout history, resulting in a population that has fluctuated both in numbers and distribution over the centuries.[citation needed]

Genetic studies on Jews show that most Jews worldwide bear a common genetic heritage which originates in the Middle East, and that they bear their strongest resemblance to the peoples of the Fertile Crescent.[68][69][70] The genetic composition of different Jewish groups shows that Jews share a common genetic pool dating back 4,000 years, as a marker of their common ancestral origin. Despite their long-term separation, Jewish communities maintained commonalities in culture, tradition, and language.[71]

Judaism

Main article: Judaism

The Jewish people and the religion of Judaism are strongly interrelated. Converts to Judaism typically have a status within the Jewish ethnos equal to those born into it.[72]

However, several converts to Judaism, as well as ex-Jews, have claimed

that converts are treated as second-class Jews by many of the born-Jews.[73]

Conversion is not encouraged by mainstream Judaism, and is considered a

difficult task. A significant portion of conversions are undertaken by

children of mixed marriages, or by would-be or current spouses of Jews.[74]The Hebrew Bible, a religious interpretation of the traditions and early national history of the Jews, established the first of the Abrahamic religions, which are now practiced by 54% of the world. Judaism guides its adherents in both practice and belief, and has been called not only a religion, but also a "way of life,"[75] which has made drawing a clear distinction between Judaism, Jewish culture, and Jewish identity rather difficult. Throughout history, in eras and places as diverse as the ancient Hellenic world,[76] in Europe before and after The Age of Enlightenment (see Haskalah),[77] in Islamic Spain and Portugal,[78] in North Africa and the Middle East,[78] India,[79] China,[80] or the contemporary United States[81] and Israel,[82] cultural phenomena have developed that are in some sense characteristically Jewish without being at all specifically religious. Some factors in this come from within Judaism, others from the interaction of Jews or specific communities of Jews with their surroundings, others from the inner social and cultural dynamics of the community, as opposed to from the religion itself. This phenomenon has led to considerably different Jewish cultures unique to their own communities.[83]

Babylon and Rome

After the destruction of the Second Temple Judaism lost much of its sectarian nature. Nevertheless, a significant Hellenized Diaspora remained, centered in Alexandria, at the time the largest urban Jewish community in the world. Hellenism was a force not just in the Diaspora but also in the Land of Israel over a long period of time. Generally, scholars view Rabbinic Judaism as having been meaningfully influenced by Hellenism.[citation needed]Without a Temple, Greek speaking Jews no longer looked to Jerusalem in the way they had before. Judaism separated into a linguistically Greek and a Hebrew / Aramaic sphere.[84]: 8–11 The theology and religious texts of each community were distinctively different.[84]: 11–13 Hellenized Judaism never developed yeshivas to study the Oral Law. Rabbinic Judaism (centered in the Land of Israel and Babylon) almost entirely ignores the Hellenized Diaspora in its writings.[84]: 13–14 Hellenized Judaism eventually disappeared as its practitioners assimilated into Greco-Roman culture, leaving a strong Rabbinic eastern Diaspora with large centers of learning in Babylon.[84]: 14–16

By the first century, the Jewish community in Babylonia, to which Jews were exiled after the Babylonian conquest as well as after the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 CE, already held a speedily growing[85] population of an estimated one million Jews, which increased to an estimated two million[86] between the years 200 CE and 500 CE, both by natural growth and by immigration of more Jews from the Land of Israel, making up about one-sixth of the world Jewish population at that era.[86] The 13th-century author Bar Hebraeus gave a figure of 6,944,000 Jews in the Roman world Salo Wittmayer Baron considered the figure convincing.[87] The figure of seven million within and one million outside the Roman world in the mid-first century became widely accepted, including by Louis Feldman. However, contemporary scholars now accept that Bar Hebraeus based his figure on a census of total Roman citizens. The figure of 6,944,000 being recorded in Eusebius' Chronicon.[88][89] Louis Feldman, previously an active supporter of the figure, now states that he and Baron were mistaken.[90]: 185 Feldman's views on active Jewish missionizing have also changed. While viewing classical Judaism as being receptive to converts, especially from the second century BCE through the first century CE, he points to a lack of either missionizing tracts or records of the names of rabbis who sought converts, as evidence for the lack of active Jewish missionizing.[90]: 205–06 Feldman maintains that conversion to Judaism was common and the Jewish population was large both within the Land of Israel and in the Diaspora.[90]: 183–203, 206 Other historians believe that conversion during the Roman era was limited in number and did not account for much of the Jewish population growth, due to various factors such as the illegality of male conversion to Judaism in the Roman world from the mid-second century. Another factor that made conversion difficult in the Roman world was the halakhic requirement of circumcision, a requirement that proselytizing Christianity quickly dropped. The Fiscus Judaicus, a tax imposed on Jews in 70 CE and relaxed to exclude Christians in 96 CE, also limited Judaism's appeal.[91]

Who is a Jew?

Main articles: Who is a Jew? and Jewish identity

Judaism shares some of the characteristics of a nation, an ethnicity,[15] a religion, and a culture, making the definition of who is a Jew vary slightly depending on whether a religious or national approach to identity is used.[92][93]

Generally, in modern secular usage Jews include three groups: people

who were born to a Jewish family regardless of whether or not they

follow the religion, those who have some Jewish ancestral background or

lineage (sometimes including those who do not have strictly matrilineal descent), and people without any Jewish ancestral background or lineage who have formally converted to Judaism and therefore are followers of the religion.[94]Historical definitions of Jewish identity have traditionally been based on halakhic definitions of matrilineal descent, and halakhic conversions. Historical definitions of who is a Jew date back to the codification of the Oral Torah into the Babylonian Talmud, around 200 CE. Interpretations of sections of the Tanakh, such as Deuteronomy 7:1–5, by Jewish sages, are used as a warning against intermarriage between Jews and Canaanites because "[the non-Jewish husband] will cause your child to turn away from Me and they will worship the gods (i.e., idols) of others." Leviticus 24:10 says that the son in a marriage between a Hebrew woman and an Egyptian man is "of the community of Israel." This is complemented by Ezra 10:2–3, where Israelites returning from Babylon vow to put aside their gentile wives and their children.[95][96] Since the anti-religious Haskalah movement of the late 18th and 19th centuries, halakhic interpretations of Jewish identity have been challenged.[97]

According to historian Shaye J. D. Cohen, the status of the offspring of mixed marriages was determined patrilineally in the Bible. He brings two likely explanations for the change in Mishnaic times: first, the Mishnah may have been applying the same logic to mixed marriages as it had applied to other mixtures (Kil'ayim). Thus, a mixed marriage is forbidden as is the union of a horse and a donkey, and in both unions the offspring are judged matrilineally.[98] Second, the Tannaim may have been influenced by Roman law, which dictated that when a parent could not contract a legal marriage, offspring would follow the mother.[98]

Ethnic divisions

Main article: Jewish ethnic divisions

Ashkenazi Jews of late 19th century Eastern Europe portrayed in Jews Praying in the Synagogue on Yom Kippur (1878), by Maurycy Gottlieb

Jews are often identified as belonging to one of two major groups: the Ashkenazim and the Sephardim. Ashkenazim, or "Germanics" (Ashkenaz meaning "Germany" in Hebrew), are so named denoting their German Jewish cultural and geographical origins, while Sephardim, or "Hispanics" (Sefarad meaning "Spain/Hispania" or "Iberia" in Hebrew), are so named denoting their Spanish/Portuguese Jewish cultural and geographic origins. The more common term in Israel for many of those broadly called Sephardim, is Mizrahim (lit. "Easterners", Mizrach being "East" in Hebrew), that is, in reference to the diverse collection of Middle Eastern and North African Jews who are often, as a group, referred to collectively as Sephardim (together with Sephardim proper) for liturgical reasons, although Mizrahi Jewish groups and Sephardi Jews proper are ethnically distinct.[100]

Smaller groups include, but are not restricted to, Indian Jews such as the Bene Israel, Bnei Menashe, Cochin Jews, and Bene Ephraim; the Romaniotes of Greece; the Italian Jews ("Italkim" or "Bené Roma"); the Teimanim from Yemen; various African Jews, including most numerously the Beta Israel of Ethiopia; and Chinese Jews, most notably the Kaifeng Jews, as well as various other distinct but now almost extinct communities.[101]

The divisions between all these groups are approximate and their boundaries are not always clear. The Mizrahim for example, are a heterogeneous collection of North African, Central Asian, Caucasian, and Middle Eastern Jewish communities that are no closer related to each other than they are to any of the earlier mentioned Jewish groups. In modern usage, however, the Mizrahim are sometimes termed Sephardi due to similar styles of liturgy, despite independent development from Sephardim proper. Thus, among Mizrahim there are Egyptian Jews, Iraqi Jews, Lebanese Jews, Kurdish Jews, Libyan Jews, Syrian Jews, Bukharian Jews, Mountain Jews, Georgian Jews, Iranian Jews and various others. The Teimanim from Yemen are sometimes included, although their style of liturgy is unique and they differ in respect to the admixture found among them to that found in Mizrahim. In addition, there is a differentiation made between Sephardi migrants who established themselves in the Middle East and North Africa after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal in the 1490s and the pre-existing Jewish communities in those regions.[101]

Ashkenazi Jews represent the bulk of modern Jewry, with at least 70% of Jews worldwide (and up to 90% prior to World War II and the Holocaust). As a result of their emigration from Europe, Ashkenazim also represent the overwhelming majority of Jews in the New World continents, in countries such as the United States, Canada, Argentina, Australia, and Brazil. In France, the immigration of Jews from Algeria (Sephardim) has led them to outnumber the Ashkenazim.[102] Only in Israel is the Jewish population representative of all groups, a melting pot independent of each group's proportion within the overall world Jewish population.[103]

Languages

Main article: Jewish languages

For centuries, Jews worldwide have spoken the local or dominant languages of the regions they migrated to, often developing distinctive dialectal forms or branches that became independent languages. Yiddish is the Judæo-German language developed by Ashkenazi Jews who migrated to Central Europe. Ladino is the Judæo-Spanish language developed by Sephardic Jews who migrated to the Iberian peninsula. Due to many factors, including the impact of the Holocaust on European Jewry, the Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries, and widespread emigration from other Jewish communities around the world, ancient and distinct Jewish languages of several communities, including Judæo-Georgian, Judæo-Arabic, Judæo-Berber, Krymchak, Judæo-Malayalam and many others, have largely fallen out of use.[5]

For over sixteen centuries Hebrew was used almost exclusively as a liturgical language, and as the language in which most books had been written on Judaism, with a few speaking only Hebrew on the Sabbath.[106] Hebrew was revived as a spoken language by Eliezer ben Yehuda, who arrived in Palestine in 1881. It had not been used as a mother tongue since Tannaic times.[104] Modern Hebrew is now one of the two official languages of the State of Israel along with Modern Standard Arabic.[107]

Despite efforts to revive Hebrew as the national language of the Jewish people, knowledge of the language is not commonly possessed by Jews worldwide and English has emerged as the lingua franca of the Jewish diaspora.[108][109][110][111][112] Although many Jews once had sufficient knowledge of Hebrew to study the classic literature, and Jewish languages like Yiddish and Ladino were commonly used as recently as the early 20th century, most Jews lack such knowledge today and English has by and large superseded most Jewish vernaculars. The three most commonly spoken languages among Jews today are Hebrew, English, and Russian. Some Romance languages, particularly French and Spanish, are also widely used.[5] Yiddish has been spoken by more Jews in history than any other language,[113] but it is far less used today following the Holocaust and the adoption of Modern Hebrew by the Zionist movement and the State of Israel. In some places, the mother language of the Jewish community differs from that of the general population or the dominant group. For example, in Quebec, the Ashkenazic majority has adopted English, while the Sephardic minority uses French as its primary language.[114][115][116][117] Similarly, South African Jews adopted English rather than Afrikaans.[118] Due to both Czarist and Soviet policies,[119][120] Russian has superseded Yiddish as the language of Russian Jews, but these policies have also affected neighboring communities.[121] Today, Russian is the first language for many Jewish communities in a number of Post-Soviet states, such as Ukraine[122][123][124][125] and Uzbekistan,[126] as well as for Ashkenazic Jews in Azerbaijan,[127] Georgia,[128] and Tajikistan.[129][130] Although communities in North Africa today are small and dwindling, Jews there had shifted from a multilingual group to a monolingual one (or nearly so), speaking French in Algeria,[131] Morocco,[127] and the city of Tunis,[132][133] while most North Africans continue to use Arabic as their mother tongue.[citation needed]

Genetic studies

Main article: Genetic studies on Jews

Y DNA

studies tend to imply a small number of founders in an old population

whose members parted and followed different migration paths.[134] In most Jewish populations, these male line ancestors appear to have been mainly Middle Eastern.

For example, Ashkenazi Jews share more common paternal lineages with

other Jewish and Middle Eastern groups than with non-Jewish populations

in areas where Jews lived in Eastern Europe, Germany and the French Rhine Valley. This is consistent with Jewish traditions in placing most Jewish paternal origins in the region of the Middle East.[135][136] Conversely, the maternal lineages of Jewish populations, studied by looking at mitochondrial DNA, are generally more heterogeneous.[137] Scholars such as Harry Ostrer and Raphael Falk

believe this indicates that many Jewish males found new mates from

European and other communities in the places where they migrated in the

diaspora after fleeing ancient Israel.[138]

In contrast, Behar has found evidence that about 40% of Ashkenazi Jews

originate maternally from just four female founders, who were of Middle

Eastern origin. The populations of Sephardi and Mizrahi Jewish

communities "showed no evidence for a narrow founder effect."[137]

Subsequent studies carried out by Feder et al. confirmed the large

portion of non-local maternal origin among Ashkenazi Jews. Reflecting on

their findings related to the maternal origin of Ashkenazi Jews, the

authors conclude "Clearly, the differences between Jews and non-Jews are

far larger than those observed among the Jewish communities. Hence,

differences between the Jewish communities can be overlooked when

non-Jews are included in the comparisons."[139][140][141]Studies of autosomal DNA, which look at the entire DNA mixture, have become increasingly important as the technology develops. They show that Jewish populations have tended to form relatively closely related groups in independent communities, with most in a community sharing significant ancestry in common.[142] For Jewish populations of the diaspora, the genetic composition of Ashkenazi, Sephardi, and Mizrahi Jewish populations show a predominant amount of shared Middle Eastern ancestry. According to Behar, the most parsimonious explanation for this shared Middle Eastern ancestry is that it is "consistent with the historical formulation of the Jewish people as descending from ancient Hebrew and Israelite residents of the Levant" and "the dispersion of the people of ancient Israel throughout the Old World".[143] North African, Italian and others of Iberian origin show variable frequencies of admixture with non-Jewish historical host populations among the maternal lines. In the case of Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews (in particular Moroccan Jews), who are closely related, the source of non-Jewish admixture is mainly southern European, while Mizrahi Jews show evidence of admixture with other Middle Eastern populations and Sub-Saharan Africans. Behar et al. have remarked on an especially close relationship of Ashkenazi Jews and modern Italians.[143][144][145] Jews were found to be more closely related to groups in the north of the Fertile Crescent (Kurds, Turks, and Armenians) than to Arabs.[146]

The studies also show that persons of Sephardic Bnei Anusim origin (those who are descendants of the "anusim" who were forced to convert to Catholicism) throughout today's Iberia (Spain and Portugal) and Ibero-America (Hispanic America and Brazil), estimated at up to 19.8% of the modern population of Iberia and at least 10% of the modern population of Ibero-America, have Sephardic Jewish ancestry within the last few centuries. The Bene Israel and Cochin Jews of India, Beta Israel of Ethiopia, and a portion of the Lemba people of Southern Africa, meanwhile, despite more closely resembling the local populations of their native countries, also have some more remote ancient Jewish descent.[147][148][149][141]

Demographics

Further information: Jewish population by country

Population centers

Main article: Jewish population by urban areas

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics there were 13,421,000 Jews worldwide in 2009, roughly 0.19% of the world's population at the time.[150]According to the 2007 estimates of The Jewish People Policy Planning Institute, the world's Jewish population is 13.2 million.[151] Adherents.com cites figures ranging from 12 to 18 million.[152] These statistics incorporate both practicing Jews affiliated with synagogues and the Jewish community, and approximately 4.5 million unaffiliated and secular Jews.[citation needed]

According to Sergio DellaPergola, a demographer of the Jewish population, in 2015 there were about 6.3 million Jews in Israel, 5.7 million in the United States, and 2.3 million in the rest of the world.[153]

Israel

Main article: Israeli Jews

Israel, the Jewish nation-state, is the only country in which Jews make up a majority of the citizens.[154] Israel was established as an independent democratic and Jewish state on 14 May 1948.[155] Of the 120 members in its parliament, the Knesset,[156] as of 2016, 14 members of the Knesset are Arab citizens of Israel (not including the Druze), most representing Arab political parties. One of Israel's Supreme Court judges is also an Arab citizen of Israel.[157]Between 1948 and 1958, the Jewish population rose from 800,000 to two million.[158] Currently, Jews account for 75.4% of the Israeli population, or 6 million people.[159][160] The early years of the State of Israel were marked by the mass immigration of Holocaust survivors in the aftermath of the Holocaust and Jews fleeing Arab lands.[161] Israel also has a large population of Ethiopian Jews, many of whom were airlifted to Israel in the late 1980s and early 1990s.[162] Between 1974 and 1979 nearly 227,258 immigrants arrived in Israel, about half being from the Soviet Union.[163] This period also saw an increase in immigration to Israel from Western Europe, Latin America, and North America.[164]

A trickle of immigrants from other communities has also arrived, including Indian Jews and others, as well as some descendants of Ashkenazi Holocaust survivors who had settled in countries such as the United States, Argentina, Australia, Chile, and South Africa. Some Jews have emigrated from Israel elsewhere, because of economic problems or disillusionment with political conditions and the continuing Arab–Israeli conflict. Jewish Israeli emigrants are known as yordim.[165]

Diaspora (outside Israel)

Main article: Jewish diaspora

The waves of immigration to the United States and elsewhere at the turn of the 19th century, the founding of Zionism and later events, including pogroms in Russia, the massacre of European Jewry during the Holocaust, and the founding of the state of Israel, with the subsequent Jewish exodus from Arab lands, all resulted in substantial shifts in the population centers of world Jewry by the end of the 20th century.[166]

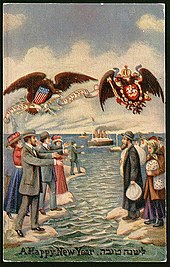

In this Rosh Hashana

greeting card from the early 1900s, Russian Jews, packs in hand, gaze

at the American relatives beckoning them to the United States. Over two

million Jews fled the pogroms of the Russian Empire to the safety of the U.S. between 1881 and 1924.[167]

Western Europe's largest Jewish community, and the third-largest Jewish community in the world, can be found in France, home to between 483,000 and 500,000 Jews, the majority of whom are immigrants or refugees from North African Arab countries such as Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia (or their descendants).[170] The United Kingdom has a Jewish community of 292,000. In Eastern Europe, there are anywhere from 350,000 to one million Jews living in the former Soviet Union, but exact figures are difficult to establish. In Germany, the 102,000 Jews registered with the Jewish community are a slowly declining population,[171] despite the immigration of tens of thousands of Jews from the former Soviet Union since the fall of the Berlin Wall.[172] Thousands of Israelis also live in Germany, either permanently or temporarily, for economic reasons.[173]

Prior to 1948, approximately 800,000 Jews were living in lands which now make up the Arab world (excluding Israel). Of these, just under two-thirds lived in the French-controlled Maghreb region, 15–20% in the Kingdom of Iraq, approximately 10% in the Kingdom of Egypt and approximately 7% in the Kingdom of Yemen. A further 200,000 lived in Pahlavi Iran and the Republic of Turkey. Today, around 26,000 Jews live in Arab countries[174] and around 30,000 in Iran and Turkey. A small-scale exodus had begun in many countries in the early decades of the 20th century, although the only substantial aliyah came from Yemen and Syria.[175] The exodus from Arab and Muslim countries took place primarily from 1948. The first large-scale exoduses took place in the late 1940s and early 1950s, primarily in Iraq, Yemen and Libya, with up to 90% of these communities leaving within a few years. The peak of the exodus from Egypt occurred in 1956. The exodus in the Maghreb countries peaked in the 1960s. Lebanon was the only Arab country to see a temporary increase in its Jewish population during this period, due to an influx of refugees from other Arab countries, although by the mid-1970s the Jewish community of Lebanon had also dwindled. In the aftermath of the exodus wave from Arab states, an additional migration of Iranian Jews peaked in the 1980s when around 80% of Iranian Jews left the country.[citation needed]

Outside Europe, the Americas, the Middle East, and the rest of Asia, there are significant Jewish populations in Australia (112,500) and South Africa (70,000).[38] There is also a 7,500-strong community in New Zealand.[citation needed]

Demographic changes

Main article: Historical Jewish population comparisons

Assimilation

Main articles: Jewish assimilation and Interfaith marriage in Judaism

Since at least the time of the Ancient Greeks,

a proportion of Jews have assimilated into the wider non-Jewish society

around them, by either choice or force, ceasing to practice Judaism and

losing their Jewish identity.[176] Assimilation took place in all areas, and during all time periods,[176] with some Jewish communities, for example the Kaifeng Jews of China, disappearing entirely.[177] The advent of the Jewish Enlightenment of the 18th century (see Haskalah) and the subsequent emancipation of the Jewish populations

of Europe and America in the 19th century, accelerated the situation,

encouraging Jews to increasingly participate in, and become part of, secular society.

The result has been a growing trend of assimilation, as Jews marry

non-Jewish spouses and stop participating in the Jewish community.[178]Rates of interreligious marriage vary widely: In the United States, it is just under 50%,[179] in the United Kingdom, around 53%; in France; around 30%,[180] and in Australia and Mexico, as low as 10%.[181][182] In the United States, only about a third of children from intermarriages affiliate with Jewish religious practice.[183] The result is that most countries in the Diaspora have steady or slightly declining religiously Jewish populations as Jews continue to assimilate into the countries in which they live.[citation needed]

War and persecution

Main article: Persecution of Jews

Further information: Antisemitism, Anti-Judaism, Orientalism, Christianity and antisemitism, Islam and antisemitism, History of antisemitism, and New antisemitism

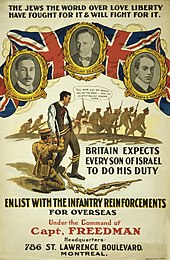

World War I

poster showing a soldier cutting the bonds from a Jewish man, who says,

"You have cut my bonds and set me free – now let me help you set others

free!"

According to James Carroll, "Jews accounted for 10% of the total population of the Roman Empire. By that ratio, if other factors had not intervened, there would be 200 million Jews in the world today, instead of something like 13 million."[186]

Later in medieval Western Europe, further persecutions of Jews by Christians occurred, notably during the Crusades—when Jews all over Germany were massacred—and a series of expulsions from the Kingdom of England, Germany, France, and, in the largest expulsion of all, Spain and Portugal after the Reconquista (the Catholic Reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula), where both unbaptized Sephardic Jews and the ruling Muslim Moors were expelled.[187][188]

In the Papal States, which existed until 1870, Jews were required to live only in specified neighborhoods called ghettos.[189]

Islam and Judaism have a complex relationship. Traditionally Jews and Christians living in Muslim lands, known as dhimmis, were allowed to practice their religions and administer their internal affairs, but they were subject to certain conditions.[190] They had to pay the jizya (a per capita tax imposed on free adult non-Muslim males) to the Islamic state.[190] Dhimmis had an inferior status under Islamic rule. They had several social and legal disabilities such as prohibitions against bearing arms or giving testimony in courts in cases involving Muslims.[191] Many of the disabilities were highly symbolic. The one described by Bernard Lewis as "most degrading"[192] was the requirement of distinctive clothing, not found in the Quran or hadith but invented in early medieval Baghdad; its enforcement was highly erratic.[192] On the other hand, Jews rarely faced martyrdom or exile, or forced compulsion to change their religion, and they were mostly free in their choice of residence and profession.[193]

Notable exceptions include the massacre of Jews and forcible conversion of some Jews by the rulers of the Almohad dynasty in Al-Andalus in the 12th century,[194] as well as in Islamic Persia,[195] and the forced confinement of Moroccan Jews to walled quarters known as mellahs beginning from the 15th century and especially in the early 19th century.[196] In modern times, it has become commonplace for standard antisemitic themes to be conflated with anti-Zionist publications and pronouncements of Islamic movements such as Hezbollah and Hamas, in the pronouncements of various agencies of the Islamic Republic of Iran, and even in the newspapers and other publications of Turkish Refah Partisi."[197]

Jews in Minsk,

1941. Before World War II some 40% of the population was Jewish. By the

time the Red Army retook the city on 3 July 1944, there were only a few

Jewish survivors.

The persecution reached a peak in Nazi Germany's Final Solution, which led to the Holocaust and the slaughter of approximately 6 million Jews.[204] Of the world's 15 million Jews in 1939, more than a third were killed in the Holocaust.[205][206] The Holocaust—the state-led systematic persecution and genocide of European Jews (and certain communities of North African Jews in European controlled North Africa) and other minority groups of Europe during World War II by Germany and its collaborators remains the most notable modern-day persecution of Jews.[207] The persecution and genocide were accomplished in stages. Legislation to remove the Jews from civil society was enacted years before the outbreak of World War II.[208] Concentration camps were established in which inmates were used as slave labour until they died of exhaustion or disease.[209] Where the Third Reich conquered new territory in Eastern Europe, specialized units called Einsatzgruppen murdered Jews and political opponents in mass shootings.[210] Jews and Roma were crammed into ghettos before being transported hundreds of miles by freight train to extermination camps where, if they survived the journey, the majority of them were killed in gas chambers.[211] Virtually every arm of Germany's bureaucracy was involved in the logistics of the mass murder, turning the country into what one Holocaust scholar has called "a genocidal nation."[212]

Migrations

Etching of the expulsion of the Jews from Frankfurt on 23 August, 1614. The text says: "1380 persons old and young were counted at the exit of the gate"

Jews fleeing pogroms, 1882

- The mythical patriarch Abraham is described as a migrant to the land of Canaan from Ur of the Chaldees[214] after an attempt on his life by King Nimrod.[215]

- The Children of Israel, in the Biblical story whose historicity is uncertain, undertook the Exodus (meaning "departure" or "exit" in Greek) from ancient Egypt, as recorded in the Book of Exodus.[216]

- Assyrian policy was to deport and displace conquered peoples, and it is estimated some 4,500,000 among captive populations suffered this dislocation over 3 centuries of Assyrian rule.[217] With regard to Israel, Tiglath-Pileser III claims he deported 80% of the population of Lower Galilee, some 13,520 people.[218] Some 27,000 Israelites, 20–25% of the population of the Kingdom of Israel, were described as being deported by Sargon II, and were replaced by other deported populations and sent into permanent exile by Assyria, initially to the Upper Mesopotamian provinces of the Assyrian Empire,[219][220]

- Between 10,000 and 80,000 people from the Kingdom of Judah were exiled by Babylonia,[217] then returned to Judea by Cyrus the Great of the Persian Achaemenid Empire,[221] and then many were exiled again by the Roman Empire.[222]

- The 2,000 year dispersion of the Jewish diaspora beginning under the Roman Empire,[citation needed] as Jews were spread throughout the Roman world and, driven from land to land,[citation needed] settled wherever they could live freely enough to practice their religion. Over the course of the diaspora the center of Jewish life moved from Babylonia[223] to the Iberian Peninsula[224] to Poland[225] to the United States[226] and, as a result of Zionism, back to Israel.[227]

- Many expulsions during the Middle Ages and Enlightenment in Europe, including: 1290, 16,000 Jews were expelled from England, see the (Statute of Jewry); in 1396, 100,000 from France; in 1421 thousands were expelled from Austria. Many of these Jews settled in Eastern Europe, especially Poland.[228]

- Following the Spanish Inquisition in 1492, the Spanish population of around 200,000 Sephardic Jews were expelled by the Spanish crown and Catholic church, followed by expulsions in 1493 in Sicily (37,000 Jews) and Portugal in 1496. The expelled Jews fled mainly to the Ottoman Empire, the Netherlands, and North Africa, others migrating to Southern Europe and the Middle East.[229]

- During the 19th century, France's policies of equal citizenship regardless of religion led to the immigration of Jews (especially from Eastern and Central Europe).[230]

- The arrival of millions of Jews in the New World, including immigration of over two million Eastern European Jews to the United States from 1880 to 1925, see History of the Jews in the United States and History of the Jews in Russia and the Soviet Union.[231]

- The pogroms in Eastern Europe,[232] the rise of modern antisemitism,[233] the Holocaust,[234] and the rise of Arab nationalism[235] all served to fuel the movements and migrations of huge segments of Jewry from land to land and continent to continent, until they arrived back in large numbers at their original historical homeland in Israel.[227]

- The Islamic Revolution of Iran caused many Iranian Jews to flee Iran. Most found refuge in the US (particularly Los Angeles) and Israel. Smaller communities of Persian Jews exist in Canada and Western Europe.[236]

- When the Soviet Union collapsed, many of the Jews in the affected territory (who had been refuseniks) were suddenly allowed to leave. This produced a wave of migration to Israel in the early 1990s.[165]

Growth

A man praying at the Western Wall

Orthodox and Conservative Judaism discourage proselytism to non-Jews, but many Jewish groups have tried to reach out to the assimilated Jewish communities of the Diaspora in order for them to reconnect to their Jewish roots. Additionally, while in principle Reform Judaism favors seeking new members for the faith, this position has not translated into active proselytism, instead taking the form of an effort to reach out to non-Jewish spouses of intermarried couples.[238]

There is also a trend of Orthodox movements pursuing secular Jews in order to give them a stronger Jewish identity so there is less chance of intermarriage. As a result of the efforts by these and other Jewish groups over the past 25 years, there has been a trend (known as the Baal Teshuva movement) for secular Jews to become more religiously observant, though the demographic implications of the trend are unknown.[239] Additionally, there is also a growing rate of conversion to Jews by Choice of gentiles who make the decision to head in the direction of becoming Jews.[240]

Leadership

Main article: Jewish leadership

There is no single governing body for the Jewish community, nor a single authority with responsibility for religious doctrine.[241]

Instead, a variety of secular and religious institutions at the local,

national, and international levels lead various parts of the Jewish

community on a variety of issues.[242]Notable individuals

Main article: Lists of Jews

Jews have made a myriad of contributions to humanity in a broad and

diverse range of fields, including the sciences, arts, politics, and

business.[243] Although Jews comprise only 0.2% of the world's population, over 20%[244][245][246][247][248][249] of Nobel Prize laureates have been Jewish or of Jewish descent, with multiple winners in each category.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen