vor allem über ein Thema diskutiert: das Coronavirus.

Dabei kam vor allem die Frage auf, ob es richtig ist,

die Corona-Toten genauer zu untersuchen oder nicht?

Eine sehr deutliche Haltung zu dem Thema hat Pathologe

Prof. Klaus Püschel. Er ist Direktor des Hamburger

Instituts für Rechtsmedizin, hat selbst bereits

50 verstorbene Corona-Patienten obduziert und

wirkt damit entgegen der Empfehlung des

Robert-Koch-Instituts (RKI).

Der Pathologe spricht bei Markus Lanz

von einer „völlig falschen Maßnahme“ des RKIs.

Püschel: „Das RKi hatte empfohlen, die Toten

nicht zu untersuchen. Das war eine völlig falsche Maßnahme.“

Lanz: „Warum?“

Püschel: „Damit von Toten keine weitere Infektionsgefahr ausgeht.

Ich denke, das ist eine Furcht, die in der Bevölkerung ist,

dass eine Untersuchung der Toten, durch den Transport von Toten,

durch den Umgang mit Toten, die Infektion verbreitet werden kann.“

Deswegen würden seiner Einschätzung nach auch weiterführende Maßnahmen

der Toten, bei denen sie geöffnet werden, bei denen tatsächlich auch

Aerosole entstehen, verhindert werden. „Ich finde aber, dass es

ein falscher Zugangsweg ist“, so Püchel.

Und auch für Markus Lanz stößt das auf Unverständnis.

„Es ist schwer nachvollziehbar, warum wir Corona-Tote nicht obduzieren.

Wir wollen doch verstehen, was im Körper dieser Menschen passiert ist.

Und genau wissen, woran sie gestorben sind.“

------------------

Die Gäste bei Markus Lanz:

Virologe Prof. Hendrik Streeck

Wissenschaftsjournalist Dirk Steffens

Pathologe Prof. Klaus Püschel

Unternehmer Martin Kind

Journalistin Anette Hilsenbeck

- Beitragslänge:

- 74 min

- Datum:

- 09.04.2020

- Verfügbarkeit:

- Video verfügbar bis 09.05.2020

Er berichtet von den Ergebnissen seines Corona-Forschungsprojektes über das stark betroffene Heinsberg. Und er erläutert, ob er eine Lockerung der Einschränkungen für möglich hält.

Dirk Steffens, Wissenschaftsjournalist

Der Terra X Moderator und Bestsellerautor erklärt, wie das Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 entstanden ist und wie Menschen durch ihr Verhalten entscheidend dazu beitragen, dass Pandemien entstehen können.

Prof. Klaus Püschel, Pathologe

"Die Angst vor dem Virus ist übertrieben", sagt der Hamburger Rechtsmediziner, der bislang 50 Corona-Tote obduziert hat. Er erzählt von seiner Arbeit und seinen Erkenntnissen.

Martin Kind, Unternehmer

Der Hörgeräte-Hersteller und Geschäftsführer von Hannover 96 spricht über die weitreichenden Auswirkungen der Pandemie auf den Profifußball. Er sagt: "Der Fußball wird sich dramatisch ändern."

Annette Hilsenbeck, Journalistin

Über 17 600 Menschen sind in Italien bisher an Corona gestorben. Die ZDF-Auslandskorrespondentin wird aus Rom in die Sendung zugeschaltet und informiert über die aktuelle Lage.

https://www.zdf.de/gesellschaft/markus-lanz/markus-lanz-vom-9-april-2020-100.html

Wie

die Coronavirus-Pandemie mit der Zerstörung von Tier- und

Pflanzenwelt zusammenhängt

DW,

16. April 2020

COVID-19

ist das aktuellste Beispiel dafür, wie der menschliche Einfluss auf

artenreiche Gebiete und Lebensräume von wilden Tieren mit der

Verbreitung von Infektionskrankheiten verknüpft ist.

Als

das neuartige Coronavirus im Dezember 2019 in der chinesischen

Großstadt Wuhan ausgebrochen war, dauerte es nicht lange, bis die

erste Hyypothese aufkam: Das Virus sei in einem nahe gelegenen

Biowaffen-Labor entwickelt worden. Wissenschaftlicher Konsens ist

hingegen: Bei dem Virus SARS-CoV-2 handelt es sich um eine Zoonose,

also eine Krankheit, die vom Tier auf den Menschen übertragen wurde.

Höchstwahrscheinlich stammt das Virus von einer Fledermaus, die dann

vermutlich ein anderes Säugetier infiziert hat, bevor es zum

Menschen wanderte.

Auch wenn

SARS-CoV-2 ganz bestimmt nicht in einem Labor entstanden ist, der

Mensch spielt bei dieser Pandemie durchaus eine Rolle. Die Eingriffe

in natürliche Lebensräume, der Rückgang der Artenvielfalt und die

Störung von Ökosystemen machen es sehr viel wahrscheinlicher, dass

solche Viren übergreifen. Das belegt eine umfassende,neue Studie von

Wissenschaftlern aus Australien und den USA.

So

haben die Ausbrüche von neu aufgetretenen Infektionskrankheiten

stark zugenommen. Seit den 1980er Jahren hat sich die Zahl alle zehn

Jahre mehr als verdreifacht. Mehr als zwei Drittel dieser Krankheiten

gehen auf Tiere zurück. Und etwa 70 Prozent davon stammen von

Wildtieren. Viele der uns bekannten Infektionskrankheiten - Ebola,

HIV, Schweine- und Vogelgrippe - sind Zoonosen.

SARS-CoV-2,

und die von ihm verursachte Krankheit COVID-19, haben noch etwas

anderes gezeigt: Durch die stark vernetzte Weltbevölkerung können

solche modernen Krankheitsausbrüche schnell zu Pandemien werden.

Viele

Menschen waren schockiert, mit welcher Geschwindigkeit sich COVID-19

weltweit ausgebreitet hat. Dabei warnen Wissenschaftler schon seit

Langem vor einer solchen Pandemie.

Durch die

Störung von Ökosystemen haben wir die Voraussetzungen dafür

geschaffen, dass Viren von Tieren auf menschliche Populationen

übergreifen können, sagt Joachim Spangenberg, Ökologe und

Vizepräsident der Forschungseinrichtung Sustainable Europe Research

Institute. "Wir schaffen diese Situation, nicht die Tiere",

sagt Spangenberg gegenüber der DW.

Abholzung und Eingriffe in die Lebensräume

Die Menschen

dringen immer weiter in die Reviere von wilden Tieren vor, holzen

Wälder ab, um Vieh zu züchten, gehen jagen und versuchen,

Ressourcen zu gewinnen. Dadurch sind sie zunehmend Krankheitserregern

ausgesetzt, die diese Orte - und die von ihnen besiedelten Tierkörper

- für gewöhnlich nie verlassen.

"Wir

kommen wilden Tieren immer näher", sagt Yan Xiang, Professor

für Virologie am Health Science Center der Universität von Texas,

"und das bringt uns mit diesen Viren in Kontakt."

"Mit

der Zunahme der menschlichen Bevölkerungsdichte und dem immer

größeren Eingriff in natürliche Lebensräume, nicht nur durch den

Menschen, sondern auch durch unsere Nutztiere, erhöhen wir das

Infektionsrisiko", sagt David Hayman, der an der Massey

Universität in Neuseeland zu Infektionskrankheiten und deren

Übertragungswegen forscht. Die Zerstörung des Ökosystems erhöht

aber nicht nur die Wahrscheinlichkeit einer Übertragung. Sie hat

auch Auswirkungen darauf, wie viele Viren es in der freien Natur gibt

und wie sie sich verhalten.

Im

vergangenen Jahrhundert wurde etwa die Hälfte der tropischen

Regenwälder, in denen etwa zwei Drittel aller Lebewesen auf der Welt

beheimatet sind, zerstört. Dieser schwerwiegende Verlust von

Lebensraum hat Auswirkungen auf das gesamte Ökosystem, auch auf die

"Teile, die wir gerne vergessen - Infektionen", sagt

Hayman.

So haben

Wissenschaftler beobachtet: Wenn Tiere am oberen Ende der

Nahrungskette verschwinden, neigen Tiere am unteren Ende der Kette,

wie Ratten und Mäuse, die mehr Krankheitserreger in sich tragen, in

einigen Fällen dazu, diesen Raum einzunehmen. "Es geht nicht

nur darum, wie viele Arten es in einem Ökosystem gibt", sagt

Alice Latinne von der Naturschutzorganisation Wildlife Conservation

Society. "Es geht auch darum, welche Arten es sind."

"Jede

Art spielt eine andere Rolle in einem Ökosystem, und manchmal, wenn

man nur eine Art durch eine andere ersetzt, kann dies enorme

Auswirkungen auf das Krankheitsrisiko haben. Und manchmal können wir

es nicht vorhersehen", sagt sie der DW.

Die

Veränderung des Lebensraums kann wilde Tiere und ihre

Krankheitserreger auch dazu zwingen, woanders hin auszuweichen –

auch in von Menschen bewohnte Gebiete. Latinne beruft sich

beispielsweise auf das Nipah-Virus, das in den späten 1990er Jahren

in Malaysia aufgetreten ist. Damals hat die Abholzung dazu geführt,

dass Flughunde ihren Lebensraum, den Wald, verlassen und sich in den

Mangobäumen von Schweinezuchtbetrieben niedergelassen haben.

Fledermäuse tragen oft Krankheitserreger in sich, die ihnen selber

nicht schaden. Doch in diesem Fall steckten sie mit ihrem Kot und

Speichel die Schweine an – und die infizierten dann die Bauern.

Es gibt also

Belege dafür, dass die Störung von Ökosystemen im Zusammenhang

steht mit dem erhöhten Risiko für neue Übertragungswege von

Krankheiten. Das ist der Grund, so Spangenberg, weshalb Experten über

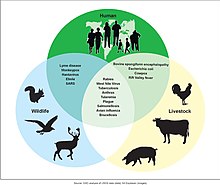

die Wichtigkeit des Konzeptes "One Health" sprechen: der

Idee, dass alles miteinander verbunden ist - die Gesundheit von

Tieren, das Ökosystem und der Mensch. Wenn eines davon aus dem

Gleichgewicht gerät, dann folgen die anderen nach.

Der Handel mit

Wildtieren

Sogenannte

"Wet markets", wo noch lebendige oder kurz vorher

geschlachtete Tiere verkauft werden, sind ein weiterer Brutkasten für

Infektionskrankheiten. Wissenschaftler glauben, dass SARS-CoV-2 mit

großer Wahrscheinlichkeit auf einem solchen Markt im chinesischen

Wuhan aufgetaucht ist.

Das

Zusammenpferchen kranker Tiere in Käfige sei in vielerlei Hinsicht

die "perfekte Umgebung", um neue Krankheitserreger

auszubrüten, sagt Spangenberg, und "ein exzellenter Weg,

Krankheiten von einer Spezies auf eine andere zu übertragen".

Deshalb sagen viele Wissenschaftler, darunter Spangenberg, dass die

Welt zumindest strenge Vorschriften braucht, die die Märkte für

lebende Tiere regulieren.

Das ist auch

die Botschaft von Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, die ein weltweites Verbot

von Wildtiermärkten fordert. Sie leitet bei den Vereinten Nationen

das Sekretariat für die Biodiversitätskonvention und betont auch,

dass Millionen von Menschen, insbesondere in einkommensschwachen

Gegenden, auf die Nahrungsmittel und das Einkommen angewiesen sind,

die ihnen diese Märkte verschaffen.

Das macht

laut Hayman die Lösungen, die den Ausbruch von Krankheiten

verhindern sollen, so schwierig. Die Ausbeutung von Tieren ist ein

Teil davon, sagt er, aber: "Armut, der Zugang zu Arbeit, wie

Menschen in entlegenen Gebieten behandelt werden, die Art und Weise,

wie Menschen mit Lebensmitteln umgehen", tragen ebenfalls zu den

Umständen bei, die zu Übertragungs-Effekten führen.

Selbst auf

wirtschaftlicher Ebene, glaubt Latinne, "werden wir gezwungen

sein, etwas zu ändern - denn die Kosten für das Auftreten von

Krankheiten und die Übertragung durch Wildtiere werden viel höher

sein, als der wirtschaftliche Nutzen durch unsere Ausbeutung der

Umwelt."

"Wir

sind Teil der Natur - wir sind Teil des Ökosystems, in dem unsere

Gesundheit mit der Gesundheit der Wildtiere, der Gesundheit des Viehs

und der Gesundheit der Umwelt verbunden ist", sagt Latinne. "Wir

müssen einen besseren Weg finden, um sicher miteinander zu leben."

Choroby odzwierzęce, zoonozy – zakaźne lub pasożytnicze choroby zwierząt, bądź przez zwierzęta tylko roznoszone, przenoszące się na człowieka poprzez kontakt bezpośredni lub surowce pochodzenia zwierzęcego, rzadziej drogą powietrzną (np. toksoplazmoza, bruceloza, wścieklizna, ptasia grypa i inne).

Nad zapobieganiem szerzeniu się chorób zakaźnych zwierząt czuwają lekarze weterynarii, natomiast leczeniem chorób odzwierzęcych u człowieka trudnią się lekarze specjaliści chorób zakaźnych.

Choroby odzwierzęce

Strony w kategorii „Choroby odzwierzęce”

Poniżej wyświetlono 49 spośród wszystkich 49 stron tej kategorii.

B

C

D

G

S

Zoonosis

Zoonosis Other names Zoönosis

A dog with rabies. Pronunciation

Specialty Infectious disease

A zoonosis (plural zoonoses, or zoonotic diseases) is an infectious disease caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, including bacteria, viruses, parasites, prions, etc) that has jumped from non-human animals (usually vertebrates) to humans.[1][2][3]

Major modern diseases such as Ebola virus disease and salmonellosis are zoonoses. HIV was a zoonotic disease transmitted to humans in the early part of the 20th century, though it has now mutated to a separate human-only disease. Most strains of influenza that infect humans are human diseases, although many strains of bird flu and swine flu are zoonoses; these viruses occasionally recombine with human strains of the flu and can cause pandemics such as the 1918 Spanish flu or the 2009 swine flu.[citation needed] Taenia solium infection is one of the neglected tropical diseases with public health and veterinary concern in endemic regions.[4] Zoonoses can be caused by a range of disease pathogens such as viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites; of 1,415 pathogens known to infect humans, 61% were zoonotic.[5] Most human diseases originated in other animals; however, only diseases that routinely involve non-human to human transmission, such as rabies, are considered direct zoonosis.[6]

Zoonoses have different modes of transmission. In direct zoonosis the disease is directly transmitted from other animals to humans through media such as air (influenza) or through bites and saliva (rabies).[7] In contrast, transmission can also occur via an intermediate species (referred to as a vector), which carry the disease pathogen without getting sick. When humans infect other animals, it is called reverse zoonosis or anthroponosis.[8] The term is from Greek: ζῷον zoon "animal" and νόσος nosos "sickness".

| Zoonosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Zoönosis |

| |

| A dog with rabies. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

A zoonosis (plural zoonoses, or zoonotic diseases) is an infectious disease caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, including bacteria, viruses, parasites, prions, etc) that has jumped from non-human animals (usually vertebrates) to humans.[1][2][3]

Major modern diseases such as Ebola virus disease and salmonellosis are zoonoses. HIV was a zoonotic disease transmitted to humans in the early part of the 20th century, though it has now mutated to a separate human-only disease. Most strains of influenza that infect humans are human diseases, although many strains of bird flu and swine flu are zoonoses; these viruses occasionally recombine with human strains of the flu and can cause pandemics such as the 1918 Spanish flu or the 2009 swine flu.[citation needed] Taenia solium infection is one of the neglected tropical diseases with public health and veterinary concern in endemic regions.[4] Zoonoses can be caused by a range of disease pathogens such as viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites; of 1,415 pathogens known to infect humans, 61% were zoonotic.[5] Most human diseases originated in other animals; however, only diseases that routinely involve non-human to human transmission, such as rabies, are considered direct zoonosis.[6]

Zoonoses have different modes of transmission. In direct zoonosis the disease is directly transmitted from other animals to humans through media such as air (influenza) or through bites and saliva (rabies).[7] In contrast, transmission can also occur via an intermediate species (referred to as a vector), which carry the disease pathogen without getting sick. When humans infect other animals, it is called reverse zoonosis or anthroponosis.[8] The term is from Greek: ζῷον zoon "animal" and νόσος nosos "sickness".

Causes[edit]

Zoonotic transmission can occur in any context in which there is companionistic (pets), economic (farming, etc.), predatory (hunting, butchering or consuming wild game) or research contact with or consumption of non-human animals, animal products, or animal derivatives.

Zoonotic transmission can occur in any context in which there is companionistic (pets), economic (farming, etc.), predatory (hunting, butchering or consuming wild game) or research contact with or consumption of non-human animals, animal products, or animal derivatives.

Contamination of food or water supply[edit]

The most significant zoonotic pathogens causing foodborne diseases are Escherichia coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, Caliciviridae, and Salmonella.[9][10][11]

In 2006, a conference held in Berlin was focusing on the issue of zoonotic pathogen effects on food safety, urging governments to intervene, and the public to be vigilant towards the risks of catching food-borne diseases from farm-to-table dining.[12]

Many food outbreaks can be linked to zoonotic pathogens. Many different types of food can be contaminated that have a non-human animal origin. Some common foods linked to zoonotic contaminations include eggs, seafood, meat, dairy, and even some vegetables.[13] Food outbreaks should be handled in preparedness plans to prevent widespread outbreaks and to efficiently and effectively contain outbreaks.

The most significant zoonotic pathogens causing foodborne diseases are Escherichia coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, Caliciviridae, and Salmonella.[9][10][11]

In 2006, a conference held in Berlin was focusing on the issue of zoonotic pathogen effects on food safety, urging governments to intervene, and the public to be vigilant towards the risks of catching food-borne diseases from farm-to-table dining.[12]

Many food outbreaks can be linked to zoonotic pathogens. Many different types of food can be contaminated that have a non-human animal origin. Some common foods linked to zoonotic contaminations include eggs, seafood, meat, dairy, and even some vegetables.[13] Food outbreaks should be handled in preparedness plans to prevent widespread outbreaks and to efficiently and effectively contain outbreaks.

Farming, ranching and animal husbandry[edit]

Contact with farm animals can lead to disease in farmers or others that come into contact with infected farm animals. Glanders primarily affects those who work closely with horses and donkeys. Close contact with cattle can lead to cutaneous anthrax infection, whereas inhalation anthrax infection is more common for workers in slaughterhouses, tanneries and wool mills.[14] Close contact with sheep who have recently given birth can lead to clamydiosis, or enzootic abortion, in pregnant women, as well as an increased risk of Q fever, toxoplasmosis, and listeriosis in pregnant or the otherwise immunocompromised. Echinococcosis is caused by a tapeworm which can be spread from infected sheep by food or water contaminated with feces or wool. Bird flu is common in chickens. While rare in humans, the main public health worry is that a strain of bird flu will recombine with a human flu virus and cause a pandemic like the 1918 Spanish flu. In 2017, free range chickens in the UK were temporarily ordered to remain inside due to the threat of bird flu.[15] Cattle are an important reservoir of cryptosporidiosis[16] and mainly affects the immunocompromised.

Practicing veterinarians are exposed to unique occupational hazards and zoonotic diseases. In the US, studies have highlighted an increased risk to injuries and a lack of veterinary awareness for these hazards. Research has proved the importance for continued clinical veterinarian education on occupational risks associated with musculoskeletal injuries, animal bites, needle-sticks, and cuts.[17]

Contact with farm animals can lead to disease in farmers or others that come into contact with infected farm animals. Glanders primarily affects those who work closely with horses and donkeys. Close contact with cattle can lead to cutaneous anthrax infection, whereas inhalation anthrax infection is more common for workers in slaughterhouses, tanneries and wool mills.[14] Close contact with sheep who have recently given birth can lead to clamydiosis, or enzootic abortion, in pregnant women, as well as an increased risk of Q fever, toxoplasmosis, and listeriosis in pregnant or the otherwise immunocompromised. Echinococcosis is caused by a tapeworm which can be spread from infected sheep by food or water contaminated with feces or wool. Bird flu is common in chickens. While rare in humans, the main public health worry is that a strain of bird flu will recombine with a human flu virus and cause a pandemic like the 1918 Spanish flu. In 2017, free range chickens in the UK were temporarily ordered to remain inside due to the threat of bird flu.[15] Cattle are an important reservoir of cryptosporidiosis[16] and mainly affects the immunocompromised.

Practicing veterinarians are exposed to unique occupational hazards and zoonotic diseases. In the US, studies have highlighted an increased risk to injuries and a lack of veterinary awareness for these hazards. Research has proved the importance for continued clinical veterinarian education on occupational risks associated with musculoskeletal injuries, animal bites, needle-sticks, and cuts.[17]

Wild animal attacks[edit]

Insect vectors[edit]

Pets[edit]

Pets can transmit a number of diseases. Dogs and cats are routinely vaccinated against rabies. Pets can also transmit ringworm and Giardia, which are endemic in both non-human animal and human populations. Toxoplasmosis is a common infection of cats; in humans it is a mild disease although it can be dangerous to pregnant women.[18] Dirofilariasis is caused by Dirofilaria immitis through mosquitoes infected by mammals like dogs and cats. Cat-scratch disease is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana from fleas which are endemic in cats. Toxocariasis is infection of humans of any of species of roundworm, including species specific to the dog (Toxocara canis) or the cat (Toxocara cati). Cryptosporidiosis can be spread to humans from pet lizards, such as the leopard gecko. Encephalitozoon cuniculi is a microsporidial parasite carried by many mammals, including rabbits, and is an important opportunistic pathogen in people immunocompromised by HIV/AIDS, organ transplantation, or CD4+ T-lymphocyte deficiency.[19]

Pets can transmit a number of diseases. Dogs and cats are routinely vaccinated against rabies. Pets can also transmit ringworm and Giardia, which are endemic in both non-human animal and human populations. Toxoplasmosis is a common infection of cats; in humans it is a mild disease although it can be dangerous to pregnant women.[18] Dirofilariasis is caused by Dirofilaria immitis through mosquitoes infected by mammals like dogs and cats. Cat-scratch disease is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana from fleas which are endemic in cats. Toxocariasis is infection of humans of any of species of roundworm, including species specific to the dog (Toxocara canis) or the cat (Toxocara cati). Cryptosporidiosis can be spread to humans from pet lizards, such as the leopard gecko. Encephalitozoon cuniculi is a microsporidial parasite carried by many mammals, including rabbits, and is an important opportunistic pathogen in people immunocompromised by HIV/AIDS, organ transplantation, or CD4+ T-lymphocyte deficiency.[19]

Exhibition[edit]

Outbreaks of zoonoses have been traced to human interaction with and exposure to other animals at fairs, petting zoos, and other settings. In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an updated list of recommendations for preventing zoonosis transmission in public settings.[20] The recommendations, developed in conjunction with the National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians, include educational responsibilities of venue operators, limiting public and non-human animal contact, and non-human animal care and management.

Outbreaks of zoonoses have been traced to human interaction with and exposure to other animals at fairs, petting zoos, and other settings. In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an updated list of recommendations for preventing zoonosis transmission in public settings.[20] The recommendations, developed in conjunction with the National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians, include educational responsibilities of venue operators, limiting public and non-human animal contact, and non-human animal care and management.

Hunting and bushmeat[edit]

Deforestation[edit]

Kate Jones, chair of ecology and biodiversity at University College London, says zoonotic diseases are Increasingly linked to environmental change and human behaviour. The disruption of pristine forests driven by logging, mining, road building through remote places, rapid urbanisation and population growth is bringing people into closer contact with animal species they may never have been near before. The resulting transmission of disease from wildlife to humans, she says, is now “a hidden cost of human economic development".[21]

Kate Jones, chair of ecology and biodiversity at University College London, says zoonotic diseases are Increasingly linked to environmental change and human behaviour. The disruption of pristine forests driven by logging, mining, road building through remote places, rapid urbanisation and population growth is bringing people into closer contact with animal species they may never have been near before. The resulting transmission of disease from wildlife to humans, she says, is now “a hidden cost of human economic development".[21]

Secondary transmission[edit]

- Ebola and Marburg

- Ebola and Marburg

Lists of diseases[edit]

Disease[22] Pathogen(s) Animals involved Mode of transmission African sleeping sickness Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense range of wild animals and domestic livestock transmitted by the bite of the tsetse fly Angiostrongyliasis Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Angiostrongylus costaricensis rats, cotton rats consuming raw or undercooked snails, slugs, other mollusks, crustaceans, contaminated water, and unwashed vegetables contaminated with larvae Anisakiasis Anisakis whales, dolphins, seals, sea lions, other marine animals eating raw or undercooked fish and squid contaminated with eggs Anthrax Bacillus anthracis commonly – grazing herbivores such as cattle, sheep, goats, camels, horses, and pigs by ingestion, inhalation or skin contact of spores Babesiosis Babesia spp. mice, other animals tick bite Baylisascariasis Baylisascaris procyonis raccoons ingestion of eggs in feces Barmah Forest fever Barmah Forest virus kangaroos, wallabies, opossums mosquito bite Bird flu Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 wild birds, domesticated birds such as chickens[citation needed] close contact Bovine spongiform encephalopathy Prions cattle eating infected meat Brucellosis Brucella spp. cattle, goats infected milk or meat Bubonic plague, Pneumonic plague, Septicemic plague, Sylvatic plague Yersinia pestis rabbits, hares, rodents, ferrets, goats, sheep, camels flea bite Capillariasis Capillaria spp. rodents, birds, foxes eating raw or undercooked fish, ingesting embryonated eggs in fecal-contaminated food, water, or soil Cat-scratch disease Bartonella henselae cats bites or scratches from infected cats Chagas disease Trypanosoma cruzi armadillos, Triatominae (kissing bug) bite Clamydiosis / Enzootic abortion Chlamydophila abortus domestic livestock, particularly sheep close contact with postpartum ewes COVID-19 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) bats, pangolins respiratory transmission Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease PrPvCJD cattle eating meat from animals with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever orthonairovirus cattle, goats, sheep, birds, multimammate rats, hares tick bite, contact with bodily fluids Cryptococcosis Cryptococcus neoformans commonly – birds like pigeons inhaling fungi Cryptosporidiosis Cryptosporidium spp. cattle, dogs, cats, mice, pigs, horses, deer, sheep, goats, rabbits, leopard geckos, birds ingesting cysts from water contaminated with feces Cysticercosis and taeniasis Taenia solium, Taenia asiatica, Taenia saginata commonly – pigs and cattle consuming water, soil or food contaminated with the tapeworm eggs (cysticercosis) or raw or undercooked pork contaminated with the cysticerci (taeniasis) Dirofilariasis Dirofilaria spp. dogs, wolves, coyotes, foxes, jackals, cats, monkeys, raccoons, bears, muskrats, rabbits, leopards, seals, sea lions, beavers, ferrets, reptiles mosquito bite Eastern equine encephalitis, Venezuelan equine encephalitis, Western equine encephalitis Eastern equine encephalitis virus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, Western equine encephalitis virus horses, donkeys, zebras, birds mosquito bite Ebola virus disease (a haemorrhagic fever) Ebolavirus spp. chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, fruit bats, monkeys, shrews, forest antelope and porcupines through body fluids and organs Other haemorrhagic fevers (Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, Dengue fever, Lassa fever, Marburg viral haemorrhagic fever, Rift Valley fever[23]) Varies – commonly viruses varies (sometimes unknown) – commonly camels, rabbits, hares, hedgehogs, cattle, sheep, goats, horses and swine infection usually occurs through direct contact with infected animals Echinococcosis Echinococcus spp. commonly – dogs, foxes, jackals, wolves, coyotes, sheep, pigs, rodents ingestion of infective eggs from contaminated food or water with feces of an infected, definitive host or fur Fasciolosis Fasciola hepatica, Fasciola gigantica sheep, cattle, buffaloes ingesting contaminated plants Foodborne illnesses (commonly diarrheal diseases) Campylobacter spp., Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Listeria spp., Shigella spp. and Trichinella spp. animals domesticated for food production (cattle, poultry) raw or undercooked food made from animals and unwashed vegetables contaminated with feces Giardiasis Giardia lamblia beavers, other rodents, raccoons, deer, cattle, goats, sheep, dogs, cats ingesting spores and cysts in food and water contaminated with feces Glanders Burkholderia mallei. horses, donkeys direct contact Gnathostomiasis Gnathostoma spp. dogs, minks, opossums, cats, lions, tigers, leopards, raccoons, poultry, other birds, frogs raw or undercooked fish or meat Hantavirus Hantavirus spp. deer mice, cotton rats and other rodents exposure to feces, urine, saliva or bodily fluids Henipavirus Henipavirus spp. horses, bats exposure to feces, urine, saliva or contact with sick horses Histoplasmosis Histoplasma capsulatum birds, bats inhaling fungi in guano Influenza Influenza A virus horses, pigs, domestic and wild birds, wild aquatic mammals such as seals and whales, minks and farmed carnivores droplets transmitted through air[24][25] Japanese encephalitis Japanese encephalitis virus pigs, water birds mosquito bite Kyasanur Forest disease Kyasanur Forest disease virus rodents, shrews, bats, monkeys tick bite La Crosse encephalitis La Crosse virus chipmunks, tree squirrels mosquito bite Leishmaniasis Leishmania spp. dogs, rodents, other animals[26][27] sandfly bite Leprosy Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium lepromatosis armadillos, monkeys, rabbits, mice[28] direct contact, including meat consumption. However, scientists believe most infections are spread human to human.[28][29] Leptospirosis Leptospira interrogans rats, mice, pigs, horses, goats, sheep, cattle, buffaloes, opossums, raccoons, mongooses, foxes, dogs direct or indirect contact with urine of infected animals Lassa fever Lassa fever virus rodents exposure to rodents Lyme disease Borrelia burgdorferi deer, wolves, dogs, birds, rodents, rabbits, hares, reptiles tick bite Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus rodents exposure to urine, feces, or saliva Melioidosis Burkholderia pseudomallei various animals direct contact with contaminated soil and surface water Microsporidiosis Encephalitozoon cuniculi Rabbits, dogs, mice, and other mammals ingestion of spores Middle East respiratory syndrome MERS coronavirus bats, camels close contact Monkeypox Monkeypox virus rodents, primates contact with infected rodents, primates, or contaminated materials Nipah virus infection Nipah virus (NiV) bats, pigs direct contact with infected bats, infected pigs Orf Orf virus goats, sheep close contact Psittacosis Chlamydophila psittaci macaws, cockatiels, budgerigars, pigeons, sparrows, ducks, hens, gulls and many other bird species contact with bird droplets Q fever Coxiella burnetii livestock and other domestic animals such as dogs and cats inhalation of spores, contact with bodily fluid or faeces Rabies Rabies virus commonly – dogs, bats, monkeys, raccoons, foxes, skunks, cattle, goats, sheep, wolves, coyotes, groundhogs, horses, mongooses and cats through saliva by biting, or through scratches from an infected animal Rat-bite fever Streptobacillus moniliformis, Spirillum minus rats, mice bites of rats but also urine and mucus secretions Rift Valley fever Phlebovirus livestock, buffaloes, camels mosquito bite, contact with bodily fluids, blood, tissues, breathing around butchered animals or raw milk Rocky Mountain spotted fever Rickettsia rickettsii dogs, rodents tick bite Ross River fever Ross River virus kangaroos, wallabies, horses, opossums, birds, flying foxes mosquito bite Saint Louis encephalitis Saint Louis encephalitis virus birds mosquito bite Severe acute respiratory syndrome SARS coronavirus bats, civets close contact, respiratory droplets Swine influenza any strain of the influenza virus endemic in pigs (excludes H1N1 swine flu, which is a human virus) pigs close contact Taenia crassiceps infection Taenia crassiceps wolves, coyotes, jackals, foxes contact with soil contaminated with feces Toxocariasis Toxocara canis, Toxocara cati dogs, foxes, cats ingestion of eggs in soil, fresh or unwashed vegetables or undercooked meat Toxoplasmosis Toxoplasma gondii cats, livestock, poultry exposure to cat feces, organ transplantation, blood transfusion, contaminated soil, water, grass, unwashed vegetables, unpasteurized dairy products and undercooked meat Trichinosis Trichinella spp. rodents, pigs, horses, bears, walruses, dogs, foxes, crocodiles, birds eating undercooked meat Tuberculosis Mycobacterium bovis infected cattle, deer, llamas, pigs, domestic cats, wild carnivores (foxes, coyotes) and omnivores (possums, mustelids and rodents) milk, exhaled air, sputum, urine, faeces and pus from infected animals Tularemia Francisella tularensis lagomorphs (type A), rodents (type B), birds ticks, deer flies, and other insects including mosquitoes West Nile fever Flavivirus birds, horses mosquito bite Zika fever Zika virus chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, monkeys, baboons mosquito bite, sexual intercourse, blood transfusion and sometimes bites of monkeys

| Disease[22] | Pathogen(s) | Animals involved | Mode of transmission |

|---|---|---|---|

| African sleeping sickness | Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense | range of wild animals and domestic livestock | transmitted by the bite of the tsetse fly |

| Angiostrongyliasis | Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Angiostrongylus costaricensis | rats, cotton rats | consuming raw or undercooked snails, slugs, other mollusks, crustaceans, contaminated water, and unwashed vegetables contaminated with larvae |

| Anisakiasis | Anisakis | whales, dolphins, seals, sea lions, other marine animals | eating raw or undercooked fish and squid contaminated with eggs |

| Anthrax | Bacillus anthracis | commonly – grazing herbivores such as cattle, sheep, goats, camels, horses, and pigs | by ingestion, inhalation or skin contact of spores |

| Babesiosis | Babesia spp. | mice, other animals | tick bite |

| Baylisascariasis | Baylisascaris procyonis | raccoons | ingestion of eggs in feces |

| Barmah Forest fever | Barmah Forest virus | kangaroos, wallabies, opossums | mosquito bite |

| Bird flu | Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 | wild birds, domesticated birds such as chickens[citation needed] | close contact |

| Bovine spongiform encephalopathy | Prions | cattle | eating infected meat |

| Brucellosis | Brucella spp. | cattle, goats | infected milk or meat |

| Bubonic plague, Pneumonic plague, Septicemic plague, Sylvatic plague | Yersinia pestis | rabbits, hares, rodents, ferrets, goats, sheep, camels | flea bite |

| Capillariasis | Capillaria spp. | rodents, birds, foxes | eating raw or undercooked fish, ingesting embryonated eggs in fecal-contaminated food, water, or soil |

| Cat-scratch disease | Bartonella henselae | cats | bites or scratches from infected cats |

| Chagas disease | Trypanosoma cruzi | armadillos, Triatominae (kissing bug) | bite |

| Clamydiosis / Enzootic abortion | Chlamydophila abortus | domestic livestock, particularly sheep | close contact with postpartum ewes |

| COVID-19 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) | bats, pangolins | respiratory transmission |

| Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease | PrPvCJD | cattle | eating meat from animals with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) |

| Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever | Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever orthonairovirus | cattle, goats, sheep, birds, multimammate rats, hares | tick bite, contact with bodily fluids |

| Cryptococcosis | Cryptococcus neoformans | commonly – birds like pigeons | inhaling fungi |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Cryptosporidium spp. | cattle, dogs, cats, mice, pigs, horses, deer, sheep, goats, rabbits, leopard geckos, birds | ingesting cysts from water contaminated with feces |

| Cysticercosis and taeniasis | Taenia solium, Taenia asiatica, Taenia saginata | commonly – pigs and cattle | consuming water, soil or food contaminated with the tapeworm eggs (cysticercosis) or raw or undercooked pork contaminated with the cysticerci (taeniasis) |

| Dirofilariasis | Dirofilaria spp. | dogs, wolves, coyotes, foxes, jackals, cats, monkeys, raccoons, bears, muskrats, rabbits, leopards, seals, sea lions, beavers, ferrets, reptiles | mosquito bite |

| Eastern equine encephalitis, Venezuelan equine encephalitis, Western equine encephalitis | Eastern equine encephalitis virus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, Western equine encephalitis virus | horses, donkeys, zebras, birds | mosquito bite |

| Ebola virus disease (a haemorrhagic fever) | Ebolavirus spp. | chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, fruit bats, monkeys, shrews, forest antelope and porcupines | through body fluids and organs |

| Other haemorrhagic fevers (Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, Dengue fever, Lassa fever, Marburg viral haemorrhagic fever, Rift Valley fever[23]) | Varies – commonly viruses | varies (sometimes unknown) – commonly camels, rabbits, hares, hedgehogs, cattle, sheep, goats, horses and swine | infection usually occurs through direct contact with infected animals |

| Echinococcosis | Echinococcus spp. | commonly – dogs, foxes, jackals, wolves, coyotes, sheep, pigs, rodents | ingestion of infective eggs from contaminated food or water with feces of an infected, definitive host or fur |

| Fasciolosis | Fasciola hepatica, Fasciola gigantica | sheep, cattle, buffaloes | ingesting contaminated plants |

| Foodborne illnesses (commonly diarrheal diseases) | Campylobacter spp., Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Listeria spp., Shigella spp. and Trichinella spp. | animals domesticated for food production (cattle, poultry) | raw or undercooked food made from animals and unwashed vegetables contaminated with feces |

| Giardiasis | Giardia lamblia | beavers, other rodents, raccoons, deer, cattle, goats, sheep, dogs, cats | ingesting spores and cysts in food and water contaminated with feces |

| Glanders | Burkholderia mallei. | horses, donkeys | direct contact |

| Gnathostomiasis | Gnathostoma spp. | dogs, minks, opossums, cats, lions, tigers, leopards, raccoons, poultry, other birds, frogs | raw or undercooked fish or meat |

| Hantavirus | Hantavirus spp. | deer mice, cotton rats and other rodents | exposure to feces, urine, saliva or bodily fluids |

| Henipavirus | Henipavirus spp. | horses, bats | exposure to feces, urine, saliva or contact with sick horses |

| Histoplasmosis | Histoplasma capsulatum | birds, bats | inhaling fungi in guano |

| Influenza | Influenza A virus | horses, pigs, domestic and wild birds, wild aquatic mammals such as seals and whales, minks and farmed carnivores | droplets transmitted through air[24][25] |

| Japanese encephalitis | Japanese encephalitis virus | pigs, water birds | mosquito bite |

| Kyasanur Forest disease | Kyasanur Forest disease virus | rodents, shrews, bats, monkeys | tick bite |

| La Crosse encephalitis | La Crosse virus | chipmunks, tree squirrels | mosquito bite |

| Leishmaniasis | Leishmania spp. | dogs, rodents, other animals[26][27] | sandfly bite |

| Leprosy | Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium lepromatosis | armadillos, monkeys, rabbits, mice[28] | direct contact, including meat consumption. However, scientists believe most infections are spread human to human.[28][29] |

| Leptospirosis | Leptospira interrogans | rats, mice, pigs, horses, goats, sheep, cattle, buffaloes, opossums, raccoons, mongooses, foxes, dogs | direct or indirect contact with urine of infected animals |

| Lassa fever | Lassa fever virus | rodents | exposure to rodents |

| Lyme disease | Borrelia burgdorferi | deer, wolves, dogs, birds, rodents, rabbits, hares, reptiles | tick bite |

| Lymphocytic choriomeningitis | Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus | rodents | exposure to urine, feces, or saliva |

| Melioidosis | Burkholderia pseudomallei | various animals | direct contact with contaminated soil and surface water |

| Microsporidiosis | Encephalitozoon cuniculi | Rabbits, dogs, mice, and other mammals | ingestion of spores |

| Middle East respiratory syndrome | MERS coronavirus | bats, camels | close contact |

| Monkeypox | Monkeypox virus | rodents, primates | contact with infected rodents, primates, or contaminated materials |

| Nipah virus infection | Nipah virus (NiV) | bats, pigs | direct contact with infected bats, infected pigs |

| Orf | Orf virus | goats, sheep | close contact |

| Psittacosis | Chlamydophila psittaci | macaws, cockatiels, budgerigars, pigeons, sparrows, ducks, hens, gulls and many other bird species | contact with bird droplets |

| Q fever | Coxiella burnetii | livestock and other domestic animals such as dogs and cats | inhalation of spores, contact with bodily fluid or faeces |

| Rabies | Rabies virus | commonly – dogs, bats, monkeys, raccoons, foxes, skunks, cattle, goats, sheep, wolves, coyotes, groundhogs, horses, mongooses and cats | through saliva by biting, or through scratches from an infected animal |

| Rat-bite fever | Streptobacillus moniliformis, Spirillum minus | rats, mice | bites of rats but also urine and mucus secretions |

| Rift Valley fever | Phlebovirus | livestock, buffaloes, camels | mosquito bite, contact with bodily fluids, blood, tissues, breathing around butchered animals or raw milk |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Rickettsia rickettsii | dogs, rodents | tick bite |

| Ross River fever | Ross River virus | kangaroos, wallabies, horses, opossums, birds, flying foxes | mosquito bite |

| Saint Louis encephalitis | Saint Louis encephalitis virus | birds | mosquito bite |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome | SARS coronavirus | bats, civets | close contact, respiratory droplets |

| Swine influenza | any strain of the influenza virus endemic in pigs (excludes H1N1 swine flu, which is a human virus) | pigs | close contact |

| Taenia crassiceps infection | Taenia crassiceps | wolves, coyotes, jackals, foxes | contact with soil contaminated with feces |

| Toxocariasis | Toxocara canis, Toxocara cati | dogs, foxes, cats | ingestion of eggs in soil, fresh or unwashed vegetables or undercooked meat |

| Toxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii | cats, livestock, poultry | exposure to cat feces, organ transplantation, blood transfusion, contaminated soil, water, grass, unwashed vegetables, unpasteurized dairy products and undercooked meat |

| Trichinosis | Trichinella spp. | rodents, pigs, horses, bears, walruses, dogs, foxes, crocodiles, birds | eating undercooked meat |

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium bovis | infected cattle, deer, llamas, pigs, domestic cats, wild carnivores (foxes, coyotes) and omnivores (possums, mustelids and rodents) | milk, exhaled air, sputum, urine, faeces and pus from infected animals |

| Tularemia | Francisella tularensis | lagomorphs (type A), rodents (type B), birds | ticks, deer flies, and other insects including mosquitoes |

| West Nile fever | Flavivirus | birds, horses | mosquito bite |

| Zika fever | Zika virus | chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, monkeys, baboons | mosquito bite, sexual intercourse, blood transfusion and sometimes bites of monkeys |

History[edit]

During most of human prehistory groups of hunter-gatherers were probably very small. Such groups probably made contact with other such bands only rarely. Such isolation would have caused epidemic diseases to be restricted to any given local population, because propagation and expansion of epidemics depend on frequent contact with other individuals who have not yet developed an adequate immune response. To persist in such a population, a pathogen either had to be a chronic infection, staying present and potentially infectious in the infected host for long periods, or it had to have other additional species as reservoir where it can maintain itself until further susceptible hosts are contacted and infected. In fact, for many 'human' diseases, the human is actually better viewed as an accidental or incidental victim and a dead-end host. Examples include rabies, anthrax, tularemia and West Nile virus. Thus, much of human exposure to infectious disease has been zoonotic.

Many modern diseases, even epidemic diseases, started out as zoonotic diseases. It is hard to establish with certainty which diseases jumped from other animals to humans, but there is increasing evidence from DNA and RNA sequencing, that measles, smallpox, influenza, HIV, and diphtheria came to humans this way. Various forms of the common cold and tuberculosis also are adaptations of strains originating in other species.

Zoonoses are of interest because they are often previously unrecognized diseases or have increased virulence in populations lacking immunity. The West Nile virus appeared in the United States in 1999 in the New York City area, and moved through the country in the summer of 2002, causing much distress. Bubonic plague is a zoonotic disease,[30] as are salmonellosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Lyme disease.

A major factor contributing to the appearance of new zoonotic pathogens in human populations is increased contact between humans and wildlife.[31] This can be caused either by encroachment of human activity into wilderness areas or by movement of wild animals into areas of human activity. An example of this is the outbreak of Nipah virus in peninsular Malaysia in 1999, when intensive pig farming began on the habitat of infected fruit bats. Unidentified infection of the pigs amplified the force of infection, eventually transmitting the virus to farmers and causing 105 human deaths.[32]

Similarly, in recent times avian influenza and West Nile virus have spilled over into human populations probably due to interactions between the carrier host and domestic animals. Highly mobile animals such as bats and birds may present a greater risk of zoonotic transmission than other animals due to the ease with which they can move into areas of human habitation.

Because they depend on the human host for part of their life-cycle, diseases such as African schistosomiasis, river blindness, and elephantiasis are not defined as zoonotic, even though they may depend on transmission by insects or other vectors.

During most of human prehistory groups of hunter-gatherers were probably very small. Such groups probably made contact with other such bands only rarely. Such isolation would have caused epidemic diseases to be restricted to any given local population, because propagation and expansion of epidemics depend on frequent contact with other individuals who have not yet developed an adequate immune response. To persist in such a population, a pathogen either had to be a chronic infection, staying present and potentially infectious in the infected host for long periods, or it had to have other additional species as reservoir where it can maintain itself until further susceptible hosts are contacted and infected. In fact, for many 'human' diseases, the human is actually better viewed as an accidental or incidental victim and a dead-end host. Examples include rabies, anthrax, tularemia and West Nile virus. Thus, much of human exposure to infectious disease has been zoonotic.

Many modern diseases, even epidemic diseases, started out as zoonotic diseases. It is hard to establish with certainty which diseases jumped from other animals to humans, but there is increasing evidence from DNA and RNA sequencing, that measles, smallpox, influenza, HIV, and diphtheria came to humans this way. Various forms of the common cold and tuberculosis also are adaptations of strains originating in other species.

Zoonoses are of interest because they are often previously unrecognized diseases or have increased virulence in populations lacking immunity. The West Nile virus appeared in the United States in 1999 in the New York City area, and moved through the country in the summer of 2002, causing much distress. Bubonic plague is a zoonotic disease,[30] as are salmonellosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Lyme disease.

A major factor contributing to the appearance of new zoonotic pathogens in human populations is increased contact between humans and wildlife.[31] This can be caused either by encroachment of human activity into wilderness areas or by movement of wild animals into areas of human activity. An example of this is the outbreak of Nipah virus in peninsular Malaysia in 1999, when intensive pig farming began on the habitat of infected fruit bats. Unidentified infection of the pigs amplified the force of infection, eventually transmitting the virus to farmers and causing 105 human deaths.[32]

Similarly, in recent times avian influenza and West Nile virus have spilled over into human populations probably due to interactions between the carrier host and domestic animals. Highly mobile animals such as bats and birds may present a greater risk of zoonotic transmission than other animals due to the ease with which they can move into areas of human habitation.

Because they depend on the human host for part of their life-cycle, diseases such as African schistosomiasis, river blindness, and elephantiasis are not defined as zoonotic, even though they may depend on transmission by insects or other vectors.

Use in vaccines[edit]

The first vaccine against smallpox by Edward Jenner in 1800 was by infection of a zoonotic bovine virus which caused a disease called cowpox. Jenner had noticed that milkmaids were resistant to smallpox. Milkmaids contracted a milder version of the disease from infected cows that conferred cross immunity to the human disease. Jenner abstracted an infectious preparation of 'cowpox' and subsequently used it to inoculate persons against smallpox. As a result, smallpox has been eradicated globally, and mass vaccination against this disease ceased in 1981.

The first vaccine against smallpox by Edward Jenner in 1800 was by infection of a zoonotic bovine virus which caused a disease called cowpox. Jenner had noticed that milkmaids were resistant to smallpox. Milkmaids contracted a milder version of the disease from infected cows that conferred cross immunity to the human disease. Jenner abstracted an infectious preparation of 'cowpox' and subsequently used it to inoculate persons against smallpox. As a result, smallpox has been eradicated globally, and mass vaccination against this disease ceased in 1981.

Zoonose

Zoonosen (von altgriechisch ζῶον zōon „Tier“ und νόσος nósos „Krankheit“) sind von Tier zu Mensch und von Mensch zu Tier übertragbare Infektionskrankheiten, die bei Wirbeltieren natürlicherweise vorkommen. Die Definition der Weltgesundheitsorganisation (WHO) von 1959 besagt einschränkend, dass Zoonosen Infektionskrankheiten sind, die auf natürliche Weise zwischen Mensch und anderen Wirbeltieren übertragen werden können.

Ursprünglich verstand man unter Zoonosen lediglich Tierkrankheiten. Während des vorletzten Jahrhunderts fand ein Wandel in der Bedeutung der Bezeichnung statt. Neben den eigentlichen Tiererkrankungen verstand man Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts unter Zoonosen nun auch Erkrankungen, die vom Tier auf den Menschen übertragen werden konnten. Beim heutigen Gebrauch der Bezeichnung Zoonose wird keine Unterscheidung hinsichtlich des Übertragungsweges gemacht. Zoonosen können also vom Menschen auf ein Tier (Anthropozoonose) oder vom Tier auf den Menschen (Zooanthroponose) übertragen werden.

Es sind gegenwärtig etwa 200 Krankheiten bekannt, die sowohl bei einem Tier wie auch beim Menschen vorkommen und in beide Richtungen übertragen werden können. Die eigentlichen Erreger können dabei Prionen, Viren, Bakterien, Pilze, Protozoen, Helminthen oder Arthropoden sein.

Begriffsgeschichte

Das Wort Zoonose wurde zum ersten Mal 1876 von Ernst Wagner in seinem Handbuch der allgemeinen Pathologie verwendet.[1]

Einteilung der Zoonosen

Nach Infektionsrichtung

Man kann die verschiedenen Zoonosen aufgrund des Reservoirs in verschiedene Gruppen einteilen.

- Zooanthroponosen: Die Infektion wird ausschließlich vom Tier auf den Menschen übertragen. Ein Beispiel ist die Infektion mit Toxocara canis.

- Anthropozoonosen: Die Infektion wird beinahe ausschließlich vom Menschen auf Tiere übertragen. Ein Beispiel ist die Infektion mit Entamoeba histolytica.

- Amphixenosen: Die Infektion kommt sowohl beim Menschen als auch beim Tier vor und wird in beide Richtungen übertragen. Ein Beispiel ist die Infektion mit Taenia saginata.

Lebenszyklus

Eine Einteilung aufgrund des Lebenszyklus ist ebenfalls möglich.

- Direkte (ortho) Zoonose: Die Zoonose wird durch direkten Kontakt oder einen mechanischen Vektor von einem Wirbeltier auf ein anderes übertragen. Ein Beispiel ist die Krätze.

- Zyklozoonose: Bei der Zyklozoonose muss der Erreger zwischen verschiedenen Wirten wechseln. Sowohl Zwischen- als auch Endwirt sind Wirbeltiere. Diese Form der Zoonose wird ausschließlich bei parasitären Erregern beobachtet, die einen heteroxenen Zyklus haben.

- Metazoonose: Bei einer Metazoonose muss der Erreger zwischen verschiedenen Wirten wechseln. Der Zwischenwirt ist ein Wirbelloser.

- Saprozoonose: Saprozoonosen haben ein Reservoir außerhalb des Tierreichs. Als Beispiele für Reservoirs zählen Pflanzen, Erde und Wasser. Beispiele für Erreger die unter diese Klasse fallen sind Giardia intestinalis, Ancylostoma und Toxocara canis.

- Latente Zoonose: Übertragung der Zoonose durch zum Beispiel Fleisch. Der Erreger verursacht beim Zwischenwirt keine Symptome.

Zoonosen und Erreger von Zoonosen

Virale Zoonosen bzw. deren Erreger

- Affenpocken

- Alkhurmavirus

- Barmah-Forest-Virus

- Büffelpocken

- California-Encephalitis-Virus

- Chikungunyafieber

- Colorado-Zeckenfieber

- Östliche Pferdeenzephalomyelitis

- Ebolafieber

- Encephalomyocarditis-Virus

- European Brown Hare Syndrom

- Gelbfiebervirus

- Hanta-Virose

- Herpes B

- Hendravirus

- Hepatitis-E-Virus

- Humane Rotaviren

- Japanische-Encephalitis-Virus

- Krim-Kongo-Hämorrhagisches-Fieber-Virus

- Kuhpocken

- Kyasanur-Forest virus

- La-Crosse-Virus

- Lassa-Virus

- Louping-Ill-Virus

- Lymphozytäre Choriomeningitis

- Marburgvirus

- Maul-und-Klauenseuche-Virus

- Menangle-Virus

- Murray-Valley-Encephalitis

- Newcastle-Disease-Virus

- Noroviren

- Orf-Virus

- Pseudokuhpocken

- Rifttalfieber-Virus

- Ross-River-Virus

- SARS

- Schweinegrippe

- Sindbisvirus

- St.-Louis-Enzephalitis-Virus

- Tahyna-Virus

- Tanapox-Virus

- Tick-borne encephalitis-Virus

- Tollwut

- Venezuelan-Equine-Encephalitis-Virus

- Vesicular stomatitis virus

- Vogelgrippe

- Wesselsbron-Virus

- West-Nil-Virus

- Western-Equine-Encephalomyelitis-Virus

Unter den Hantavirosen sind Viren mit pulmonaler Symptomatik wie das Sin-Nombre-Virus, das Black-Creek-Canal-Virus, das Muleshoe-Virus, das Bayouvirus, das Andesvirus, das Bermejovirus, das Choclovirus, das Araraquaravirus, das Juquitibavirus, das Macielvirus und das Castelo-dos-Sonhos-Virus sowie Hantaviren mit renaler Symptomatik wie das Hantaan-Virus, das Dobrava-Virus, das Puumala-Virus und das Seoul-Virus.

Prion-induzierte Zoonosen

- Transmissible spongiforme Enzephalopathie (TSE) einschließlich BSE der Rinder und Scrapie der Schafe

Bakterielle Zoonosen

- Campylobacter-Enteritis

- Bartonellosen

- Borreliose

- Brucellose

- Leptospirose

- Listeriose

- Milzbrand

- Ornithose

- Pest

- Psittakose (Ornithose)

- Rotlauf

- Salmonellose

- Tuberkulose

- Tularämie

- Q-Fieber (Balkan-Grippe)

Zoonotische Mykosen

Parasitäre Zoonosen

Einzeller

- Babesiose

- Chagas-Krankheit

- Kryptosporidiose

- Encephalitozoonose

- Giardiasis

- Leishmaniose

- Malaria

- Sarcocystiose

- Toxoplasmose

Würmer

- Anisakiasis

- Ancylostomiasis

- Askariasis

- Bethriozephalose

- Dirofilariose

- Dipylidiasis

- Echinokokkose

- Fasziolose

- Schistosomiasis

- Taeniasis

- Toxocariasis

- Trichinellose

- Zystizerkose

Arthropoden

- Milben (Acari)

Vorkommen

Die Inzidenz und Prävalenz der meisten Zoonosen ist schwer einzuschätzen. Einerseits bleiben viele Zoonosen undiagnostiziert, andererseits besteht für die meisten Zoonosen keine Anzeigepflicht.

Allgemein ist jedoch die Gefahr, sich mit einer Zoonose zu infizieren, umso größer, je häufiger und je direkter ein Kontakt mit Tieren besteht.

Essgewohnheiten können einen Einfluss auf die Verbreitung von Zoonosen haben. So ist die Prävalenz von Toxoplasmose in England niedriger als in Frankreich, weil Engländer weniger rohes oder angebratenes Fleisch essen. Zystizerkose, ein Befall des Menschen mit Larven des Schweinebandwurms, kommt in jüdischen oder islamischen Bevölkerungsgruppen nicht vor, da diese kein Schweinefleisch essen.

Die Zerstörung unberührter Wälder durch Abholzung, Bergbau, Straßenbau durch abgelegene Orte, rasche Verstädterung und Bevölkerungswachstum bringt die Menschen in Kontakt mit wilden Tierarten, von denen Krankheitserreger auf menschliche Gemeinschaften überspringen können.[2]

Gefahren

Die Salmonellose wird vor allem über Lebensmittel (Eier, Milchprodukte, Geflügelfleisch) übertragen. Sie ist die am häufigsten gemeldete Zoonose. Hohe Temperaturen erhöhen die Gefahr, dass sich Salmonellen in Lebensmitteln vermehren.

In Deutschland kam es 2005 zu mehreren Todesfällen durch Tollwut. Eine Patientin infizierte sich in Indien mit der Tollwut. Die Symptome der Krankheit wurden damals dem Drogenkonsum der Patientin zugeschrieben und so kam es nach dem Tod der Patientin zu Infektionen bei mehreren Organtransplantierten, die Organe von der Patientin erhielten.

Immuninkompetente Menschen (Menschen mit einem durch eine andere Erkrankung schon stark geschwächten oder gar vollständig funktionsunfähigen Immunsystem), wie zum Beispiel Aids-Patienten im fortgeschrittenen Stadium oder Menschen die sich einer Chemotherapie unterziehen, immunschwache Menschen, wie zum Beispiel alte Menschen oder Kinder, sind zusätzlich der Gefahr ausgesetzt, sich mit Erregern zu infizieren, die normalerweise bei Menschen nicht zu patenten Infektionen führen (die Phase einer Parasiteninfektion eines Organismus ab dem Zeitpunkt der abgeschlossenen Entwicklung der Eindringlinge zu erwachsenen, eierlegenden Parasiten und dem ersten Auftreten ihrer Fortpflanzungsprodukte in den Körperausscheidungen des Wirtes).

Eine spezielle Gefahr besteht für Schwangere. Manche Zoonosen können eine Schädigung des Fötus verursachen. Auch Neugeborene haben noch ein relativ schwaches Immunsystem und können durch sonst harmlose Infektionen stark gefährdet werden. Noch stärker gefährdet sind besonders Kinder, die nicht gestillt werden, da gerade durch die Muttermilch auch die mütterlichen Abwehrkräfte auf den Säugling mit übertragen werden.

Bestimmte Berufsgruppen, wie zum Beispiel Tierärzte oder Landwirte, haben ein erhöhtes Infektionsrisiko, da sie oft mit Vektoren zusammentreffen.

Prävention

Jeder Mensch, der mit Tieren oder ihren Produkten in Berührung kommt, kann einer Infektion ausgesetzt werden. Dabei ist es unerheblich, ob der Mensch Tiere bejagt oder als Nutz- oder Haustiere domestiziert. Infektionen von Tieren auf Menschen werden durch die gleichen Maßnahmen vermieden wie zwischenmenschliche Infektionen. Bei der Tierhaltung gilt Hygiene[3] (saubere Ställe und Gehege, Reinigen der Hände, Desinfektion, etwa durch Kochen und Bügeln von Textilien) als wichtigste Vorbeugungsmaßnahme. Auch zu inniger Kontakt zwischen Tier und Mensch kann eine Infektionsübertragung provozieren.

Die Ausrottung gefährlicher Zoonosen, wie zum Beispiel der Tuberkulose, beziehungsweise die Bekämpfung von Erregern durch regelmäßige Behandlungen, wie zum Beispiel Impfungen oder Entwurmung, trägt dazu bei, das allgemeine Infektionsrisiko zu verringern.

Auch gesund erscheinende Tiere können eine Quelle für Infektionen sein, die tödlich enden können. Ein Beispiel hierfür ist die Übertragung von Herpesviren durch Affen auf Menschen.

Seuchengefahr

Die Gefahr von seuchenartigem Auftreten ist auch bei einigen Zoonosen gegeben. Ein Beispiel für eine solche Seuche ist die Pest. Viele andere Zoonosen sind in ihrem Seuchenpotential eher begrenzt, da sie den Kontakt zwischen Wirt oder Vektor und Mensch voraussetzen.

Eine besondere Gefahr, die allerdings nicht mehr zu den Zoonosen zu zählen ist, ist ein Wirtswechsel. Findet ein Wirtswechsel statt, zum Beispiel vom Vogel oder der Katze auf den Menschen, können dadurch Pandemien ausgelöst werden. In jüngster Vergangenheit fand ein solcher Wechsel zwischen Katzen und Menschen in Asien statt. Ein für die Lungenkrankheit SARS verantwortliches Coronavirus, das SARS-assoziierte Coronavirus, mutierte und konnte von seinem natürlichen Wirt (einer Katzenart) plötzlich auf den Menschen übertragen werden und schlimmer noch, sich dort vermehren und durch den Menschen weiter übertragen werden.

Ein Fall zu Beginn der Influenza-Pandemie 2009 in Kanada zeigte, dass sich Influenzaviren des Subtyps H1N1 potentiell auf natürliche Weise von Mensch zu Tier übertragen können.[4][5] Die Canadian Food Inspection Agency stufte im Mai 2009 die Übertragung der Viren vom Mensch zum Schwein als höchstwahrscheinlich ein. In solchen Fällen einer Zoonose besteht die Gefahr, dass sich Viren im Erregerreservoir neu kombinieren und beispielsweise für Menschen gefährlichere Erreger bilden.[5]

Überwachung und Forschungsanstrengungen

AIDS, SARS und die dadurch hervorgerufenen Erinnerungen an die Spanische Grippe haben das Interesse an der Erforschung von Zoonosen verstärkt. So regte die Europäische Union ein europaweites Netzwerk namens Med-Vet-Net von 300 Forschern an, das sich der Prävention und Kontrolle von Zoonosen widmet. Ein Schwerpunkt des Netzwerkes sind die Campylobacteriosen, Infektionen des Verdauungstraktes z. B. von Campylobacter jejuni, von denen bisher 100 Bakterienstämme identifiziert sind. Der Europäische Rat und das Europäische Parlament haben 2003 eine Liste A von acht Zoonosen definiert, die kontinuierlich überwacht werden. Dazu gehören Krankheiten, die durch Bakterienstämme der Familien Campylobacter, Listeria, Salmonella, bestimmte Arten Escherichia coli oder das Mycobacterium bovis ausgelöst werden, sowie die von Parasiten hervorgerufenen Trichinellose und Echinokokkose. In einer Liste B wurden Zoonosen definiert, bei denen die Überwachung beginnt, sobald ein Fall identifiziert ist. Dazu gehören Tollwut, West-Nil-Fieber und Vogelgrippe.[1]

Literatur

- Pedro N. Acha, Boris Szyfres: Zoonoses and Communicable Diseases Common to Man and Animals. Volume 1: Bacterioses and Mycoses. 3rd ed., 2nd print. PAHO Pan American Health Organization, Washington DC 2003, ISBN 92-75-11580-X

- Pedro N. Acha, Boris Szyfres: Zoonoses and Communicable Diseases Common to Man and Animals. Volume 2: Chlamydioses, Rickettsioses, and Viroses. 3rd ed. PAHO Pan American Health Organization, Washington DC 2003, ISBN 92-75-11992-9

- Pedro N. Acha, Boris Szyfres: Zoonoses and Communicable Diseases Common to Man and Animals. Volume 3: Parasitoses. 3rd ed. PAHO Pan American Health Organization, Washington DC 2003, ISBN 92-75-11993-7

- P. Kimmig, T. Schwarz, H. G. Schiefer, W. Slenczka, H. Zahner: Zoonosen. Von Tier zu Mensch übertragbare Infektionskrankheiten. Mit CD-ROM. Hrsg.: Rolf Bauerfeind. 4. Auflage. Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag, Köln 2013, ISBN 978-3-7691-1293-1.

- Carolin Anna Maria Bumann: Nachweis lebensmittelhygienisch relevanter bakterieller Zoonoseerreger bei kleinen Wiederkäuern aus der Schweiz. LMU, München 2010, DNB 1007628111 (202 S., Volltext [PDF; 1000 kB] Dissertation, Universität München, 2010).

- Michael R. Conover & Rosanna M. Vail: Human Diseases from Wildlife. CRC Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4665-6214-1 (Print), ISBN 978-1-4665-6215-8 (eBook)

- Józef Parnas: Menschliche Infektionskrankheiten tierischer Herkunft für Ärzte und Tierärzte. 3 Bände, Kopenhagen 1975.

- Manfred Vasold: Zoonosen. In: Werner E. Gerabek, Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil, Wolfgang Wegner (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4, S. 1532–1534.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen