ŻYDOKOMUNA

CZYLI

MIECZ DAMOKLESA

WISZĄCY NAD

WOLNĄ POLSKĄ,

WOLNĄ EUROPĄ

I WOLNYM ŚWIATEM

Żydowski Instytut Historyczny

im. Emanuela Ringelbluma

ul. Tłomackie 3/5

00–090 Warszawa

tel.: (22) 827 92 21

fax: (22) 827 83 72

00–090 Warszawa

tel.: (22) 827 92 21

fax: (22) 827 83 72

DYREKCJA

prof. dr hab. Paweł Śpiewak — dyrektor

Sekretariat

tel.: (22) 827

92 21 w. 113

tel./fax: (22) 827 83 72

e-mail: secretary@jhi.pl

tel./fax: (22) 827 83 72

e-mail: secretary@jhi.pl

Książka dyrektora o której tu mowa, nie należy do gatunku literackiego, który kojarzymy z fantastyką lub innymi podobnymi formami narracji lecz

zajmuje się analizą faktów. Zbiór faktów nie jest określany mianem mitologii

lecz faktografii. Oba pojęcia są wewnętrznie

sprzeczne i wykluczają sie wzajemnie. Innymi słowy to, co jest mitem nie może

być faktem a fakt nie jest mitem. Naczelną rolę w logice i nauce odgrywa zasada

niesprzeczności, według której twierdzenia sprzeczne nie mogą być równocześnie

prawdziwe. Teza autora o rzekomym wymyśleniu mitu o żydokomunie przeczy

oczywistym faktom o jej subwersywnym i zbrodniczym działaniu. W świetle tych wyjaśnień powstaje pytanie: Kto nadał temu żydowskiemu agitatorowi tytuły naukowe i dał mu stanowisko profesora?

Krytycznie, jasno i politycznie myślący czytelnik łatwo dojdzie do wniosku,

że opierając się na klasycznej definicji pojęcia mitu nie jest możliwe prawidłowe określenie jego znaczenia jeżeli

jego konotacja odnosi się do faktów. Konotacja nazwy

"żydokomuna", warstwa skojarzeniowa tego słowa i sposób posługiwania się nim przez ludzi nie ma nic wspólnego z legendą,

baśnią, bajką, utopią lub w ogólności z formami narracyjnymi, odnoszącymi się do świata istot nadprzyrodzonych.

Autor przeczy sam sobie zbierając niezbite niepodważalne fakty dotyczące spiskowej, antynarodowej, zdradzieckiej i zbrodniczej działalności polskiej żydokomuny, która była i jest historyczną kontynuacją żydokomuny bolszewickiej, i jednocześnie fakty te umieszcza w świecie mitologii lub też traktuje ich percepcję w kategoriach masowej aberracji społecznej. Dyrektor ŻIH jest więc w tej roli nie obiektywnym historykiem, który w sposób naukowo dopuszczalny komentuje fakty lecz żydowskim propagandystą, agitatorem zamętu pojęciowego i bezczelnym łgarzem.

Autor przeczy sam sobie zbierając niezbite niepodważalne fakty dotyczące spiskowej, antynarodowej, zdradzieckiej i zbrodniczej działalności polskiej żydokomuny, która była i jest historyczną kontynuacją żydokomuny bolszewickiej, i jednocześnie fakty te umieszcza w świecie mitologii lub też traktuje ich percepcję w kategoriach masowej aberracji społecznej. Dyrektor ŻIH jest więc w tej roli nie obiektywnym historykiem, który w sposób naukowo dopuszczalny komentuje fakty lecz żydowskim propagandystą, agitatorem zamętu pojęciowego i bezczelnym łgarzem.

Krętacze żydowscy, specjaliści od łgarstw, przeinaczania znaczeń, przekręcania

faktów, gwałcenia prawdy historycznej i manipulowania opinią publiczną dla

własnych celów czynią wszystko, żeby zbagatelizować rolę Żydów w ich zbrodniach

i lewicowego żydowstwa w jej kreciej robocie skierowanej przeciwko interesom gospodarzy, tych narodów,

u których są w gościnie.

Wyciągnij palec w ich stronę, chcą, żeby im podać rękę – podasz im rękę na pomoc, pytają o ramię na wsparcie – podasz im pomocne ramię... urwą ci głowę!

Gospodarzu! Strzeż się przed takimi gośćmi, jeżeli chcesz zapobiec, żeby przytrafiło ci się nieszczęście. Polsko! Strzeż się przed takimi mieszkańcami, jeżeli nie chcesz, żeby skończyło się to katastrofą. Europo i Wolny Świecie! Miejcie się na baczności przed żydowską propagandą, agitacją i postawą implikującą lewicową kosmopolityczną dyktaturę światopoglądową (niem. linke Gesinnungsdiktatur), jeżeli nie chcecie zamętu i wojny.

Istnieje w języku hebrajskim odpowiednie słowo, które adekwatnie oddaje charakter i sposób zachowania się, z którym mamy tu do czynienia mianowicie: chucpa. Chucpa, określenie głęboko wrośnięte w żydowska kulturę, to bezczelność, zuchwałość, tupet, arogancja, buta, butność, impertynencja, nadętość, pyszałkowatość, zarozumiałość, zuchwalstwo, zuchwałość, arogancja, draństwo, granda, kpina, łajdactwo, megalomania, mitomania, niegodziwość, niegrzeczność, snobizm, zadufanie, zniewaga, grubiaństwo, nieokrzesanie, ordynarność, prostactwo, wulgarność lub chamstwo – wszystkie te cechy szczególnie często spotykane u Żydów, kiedy chodzi im o to, żeby łgać w żywe oczy, bezwstydnie kłamać jak z nut i oszukiwać jawnie społeczeństwo mając przy tym tylko i wyłącznie własne interesy na uwadze. Ale naród polski ciężko doświadczony historycznie nabrać się nie da na te bezwstydne żydowskie fałszywki.

POLAKU! NIE BĄDŹ SZABASGOJEM!

I PAMIĘTAJ O TWIOM ŚWIĘTYM PATRIOTYCZNYM OBOWIĄZKU: ODŻYDZAJ NARÓD I OJCZYZNĘ!

Wyciągnij palec w ich stronę, chcą, żeby im podać rękę – podasz im rękę na pomoc, pytają o ramię na wsparcie – podasz im pomocne ramię... urwą ci głowę!

Gospodarzu! Strzeż się przed takimi gośćmi, jeżeli chcesz zapobiec, żeby przytrafiło ci się nieszczęście. Polsko! Strzeż się przed takimi mieszkańcami, jeżeli nie chcesz, żeby skończyło się to katastrofą. Europo i Wolny Świecie! Miejcie się na baczności przed żydowską propagandą, agitacją i postawą implikującą lewicową kosmopolityczną dyktaturę światopoglądową (niem. linke Gesinnungsdiktatur), jeżeli nie chcecie zamętu i wojny.

Istnieje w języku hebrajskim odpowiednie słowo, które adekwatnie oddaje charakter i sposób zachowania się, z którym mamy tu do czynienia mianowicie: chucpa. Chucpa, określenie głęboko wrośnięte w żydowska kulturę, to bezczelność, zuchwałość, tupet, arogancja, buta, butność, impertynencja, nadętość, pyszałkowatość, zarozumiałość, zuchwalstwo, zuchwałość, arogancja, draństwo, granda, kpina, łajdactwo, megalomania, mitomania, niegodziwość, niegrzeczność, snobizm, zadufanie, zniewaga, grubiaństwo, nieokrzesanie, ordynarność, prostactwo, wulgarność lub chamstwo – wszystkie te cechy szczególnie często spotykane u Żydów, kiedy chodzi im o to, żeby łgać w żywe oczy, bezwstydnie kłamać jak z nut i oszukiwać jawnie społeczeństwo mając przy tym tylko i wyłącznie własne interesy na uwadze. Ale naród polski ciężko doświadczony historycznie nabrać się nie da na te bezwstydne żydowskie fałszywki.

POLAKU! NIE BĄDŹ SZABASGOJEM!

I PAMIĘTAJ O TWIOM ŚWIĘTYM PATRIOTYCZNYM OBOWIĄZKU: ODŻYDZAJ NARÓD I OJCZYZNĘ!

Polaku! Pamiętaj, że żydokomuna – to ani mit, ani teoria spiskowa ani antysemicki stereotyp - jak wciskają ci do głowy żydowscy łgarze i fałszerze historii - tylko fakt stworzenia przez

Żydów komunizmu, który dał im władzę przejętą na drodze terroru, zbrodni, ludobójstwa, masowego mordu i kłamliwej propagandy, władzę, która miała i ma w dalszym ciągu im otworzyć drogę do zdobycia władzy nad światem - w zgodzie z założeniami i dążeniami wszechświatowego syjonizmu.

Jerzy Chojnowski

Chairman-GTVRG e.V.

www.gtvrg.de

PS. Dla wyjaśnienia: Mit (stgr. μῦθος) – opowieść o bóstwach i istotach nadprzyrodzonych, przekazywana przez daną społeczność, zawierająca w sobie wyjaśnienie sensu świata i ludzi w ich doświadczeniach zbiorowych oraz indywidualnych (według definicji etnoreligijnej) lub wywodzące się z tradycji ustnej ponadczasowe, anonimowe opowiadanie o postaciach nadprzyrodzonych, które trwa w kulturze dzięki ciągłym transformacjom i reinterpretacjom dokonywanym przez pisarzy, przy zachowaniu jednocześnie swojego pierwotnego sensu.

PS. Dla wyjaśnienia: Mit (stgr. μῦθος) – opowieść o bóstwach i istotach nadprzyrodzonych, przekazywana przez daną społeczność, zawierająca w sobie wyjaśnienie sensu świata i ludzi w ich doświadczeniach zbiorowych oraz indywidualnych (według definicji etnoreligijnej) lub wywodzące się z tradycji ustnej ponadczasowe, anonimowe opowiadanie o postaciach nadprzyrodzonych, które trwa w kulturze dzięki ciągłym transformacjom i reinterpretacjom dokonywanym przez pisarzy, przy zachowaniu jednocześnie swojego pierwotnego sensu.

"Żydokomuna" to antysemicki mit - pisze Paweł Śpiewak w książce

"Żydokomuna. Interpretacje historyczne". Jednocześnie jednak autor

przedstawia liczby, które mogą być interpretowane jako dowód na duże

poparcie Żydów dla komunizmu.

"Żydokomuna" to antysemicki mit - pisze Paweł Śpiewak w książce

"Żydokomuna. Interpretacje historyczne". Jednocześnie jednak autor

przedstawia liczby, które mogą być interpretowane jako dowód na duże

poparcie Żydów dla komunizmu.

Mit "żydokomuny"

Paweł Śpiewak, dyrektor Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, wielokrotnie podkreśla w swej książce, że żydokomuna to nie realne zjawisko a ideologiczny mit, w którym zbiegły się wszystkie antysemickie stereotypy z wielowiekowej tradycji oskarżania Żydów o wszelkie dziejące się zło.Zdaniem Śpiewaka termin "żydokomuny" dawał możliwość głoszenia twierdzeń, że wszyscy Żydzi są nosicielami wrogiej ideologii, czyli bolszewizmu. Struktura mitu "żydokomuny", według Śpiewaka, zaczerpnięta została z „Protokołów mędrców Syjonu", znanej fałszywki carskiej policji politycznej, która głosiła, że wykorzenieni z ziemi, rozprzestrzenieni w świecie Żydzi nigdy nie wrosną w narody, wśród których mieszkają, łączy ich natomiast wspólny cel, jakim jest panowanie nad światem, do którego realizacji używają i bolszewizmu, i kapitalizmu.

"Mit żydokomuny żywił się wyolbrzymianymi faktami. Wskazywano na +niewłaściwe+ pochodzenie wielu liderów sowieckiej rewolucji, gazety w okresie międzywojennym podkreślały żydowskie nazwiska aresztowanych komunistów, po wojnie liczono Żydów w Biurze Politycznym i w urzędach bezpieczeństwa" - pisze Śpiewak."Mit żydokomuny żywił się wyolbrzymianymi faktami. Wskazywano na +niewłaściwe+ pochodzenie wielu liderów sowieckiej rewolucji, gazety w okresie międzywojennym podkreślały żydowskie nazwiska aresztowanych komunistów, po wojnie liczono Żydów w Biurze Politycznym i w urzędach bezpieczeństwa" - pisze Śpiewak.

Komunizm i Żydzi

Samo słowo "żydokomuna" pojawiło się dopiero po wojnie, wcześniej to zjawisko określano, jako judeobolszewizm lub żydobolszewizm. Jako socjolog Śpiewak próbuje wskazać przyczyny, dla których komunizm okazał się na początku XX wieku atrakcyjny dla Żydów. W przedrewolucyjnej Rosji część Żydów pozbawiona była praw obywatelskich, większość mogła się osiedlać tylko na ściśle określonym obszarze. Rewolucja po raz pierwszy w historii dała rosyjskim Żydom pełnię swobód obywatelskich oraz możliwość pracy w administracji.Także w II RP obowiązywało niepisane prawo ograniczające dostęp ludności żydowskiej do stanowisk w administracji, wojsku, szkolnictwie, na uczelniach obowiązywało getto ławkowe i numerus clausus. Śpiewak zauważa, że w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym młodzi, aspirujący do wyjścia z religijnego getta Żydzi, nie mieli atrakcyjniejszej propozycji niż proklamujące równość społeczną ruchy lewicowe.

Jako socjolog Śpiewak próbuje wskazać przyczyny, dla których komunizm okazał się na początku XX wieku atrakcyjny dla Żydów. W przedrewolucyjnej Rosji część Żydów pozbawiona była praw obywatelskich, większość mogła się osiedlać tylko na ściśle określonym obszarze. Rewolucja po raz pierwszy w historii dała rosyjskim Żydom pełnię swobód obywatelskich oraz możliwość pracy w administracji.Od rewolucji 1905 roku Śpiewak datuje powszechniejsze niż dotychczas angażowanie się Żydów w życie polityczne - wtedy powstały żydowskie partie syjonistyczne a także lewicowy Bund. Ale rewolucji bolszewickiej większość sił żydowskich w Rosji była początkowo niechętna. Do poparcia bolszewików pchały ich pogromy, których fala przetoczyła się wtedy przez Rosję. Oblicza się, że między rokiem 1918 a 1921 na terenach Ukrainy i Białorusi wymordowano między 200 a 300 tysięcy Żydów. Większość pogromów zdarzyła się na terenach kontrolowanych przez siły białych i dlatego, choć Armia Czerwona także czasami organizowała pogromy, większość Żydów uznała, że porządek rewolucyjny zapewnia im więcej bezpieczeństwa, szansę na przetrwanie - uważa Śpiewak.

Po rewolucji sytuacja Żydów w ZSRR zmieniła się na korzyść: mogli się swobodnie osiedlać w całym kraju, zlikwidowano numerus clausus w szkołach, po raz pierwszy w historii Rosji Żydzi wchodzili do aparatu władzy. Obejmując posady po wyrzucanych urzędnikach carskich, wykształcone żydostwo stało się dla nowej władzy rezerwuarem kadr. Wielu Żydów znalazło się też na samej górze sowieckiego aparatu władzy.

Żydzi wobec Komunistycznej Partii Polski i Sowietów

Także w Polsce w latach międzywojnia widać było, że ideologia komunistyczna jest dla Żydów atrakcyjna. Dyrektor ŻIH skrupulatnie wylicza dane: do Komunistycznej Partii Polski w 1933 roku należało 8 tys. osób z czego 80 proc. stanowili Polacy, a około 20 proc. Żydzi. W dużych miastach proporcje układały się inaczej - w Warszawie w 1937 roku 65 proc. członków partii stanowili Żydzi. Przedwojenny Związek Młodzieży Komunistycznej Polski, liczący w połowie lat 30. niemal 12 tys. członków, w 42 proc. składał się z osób pochodzenia żydowskiego.Sami komuniści zauważali, że Żydzi są w KPP nadreprezentowani. W materiałach z 1929 roku znalazły się dane, że "towarzysze żydowscy w miastach stanowią przeważnie ponad 50 proc. składu organizacji, a są miasteczka, w których organizacja jest czysto żydowska". Proporcje narodowościowe przechylały się na korzyść Żydów w zarządzie partii. W styczniu 1936 roku na 30 członków Komitetu Centralnego KPP było 15 Polaków, 12 Żydów, 2 Ukraińców i 1 Białorusin.

Wobec faktu, że Żydzi stanowili ok. 10 proc. przedwojennej ludności Polski można z tych liczb wyciągnąć wniosek o nadreprezantacji Żydów w strukturach komunistycznych. Śpiewak jednak zwraca uwagę, że ogromna większość polskich Żydów nie chciała mieć z komunizmem nic wspólnego. Na KPP głosowało w 1928 roku 7 proc. społeczności żydowskiej, zaś 50 proc. polskich Żydów oddało głosy na Bezpartyjny Blok Współpracy z Rządem, czyli partię Piłsudskiego. Bardzo wielu Żydów głosowało też na partie syjonistyczne. Komunistów, którzy tworzyli KPP spotkał straszny los. Partia została przez Stalina rozwiązana w końcu 1937 roku, w okresie Wielkiej Czystki w ZSRR zamordowano 70 proc. aktywu kierowniczego KPP, przeżyli w zasadzie tylko ci z jej kierownictwa, którzy siedzieli w tym czasie w polskich więzieniach m.in. w Berezie Kartuskiej.

W pierwszych latach okupacji na terenach zajętych przez Sowietów podniosła się fala agresywnego antysemityzmu, który zaowocował w 1941 roku takimi wydarzeniami jak pogrom w Jedwabnem. W dokumentach z epoki pojawiają się relacje o entuzjastycznym przyjęciu przez Żydów sowieckiej władzy, powszechnej wśród nich współpracy z komunistyczną władzą, donosicielstwie i przejmowaniu stanowisk polskich urzędników. Stereotyp żydokomuny zyskał w tym czasie wśród Polaków wielu zwolenników.

Śpiewak zwraca uwagę, że ogromna większość polskich Żydów nie chciała mieć z komunizmem nic wspólnego. Na KPP głosowało w 1928 roku 7 proc. społeczności żydowskiej, zaś 50 proc. polskich Żydów oddało głosy na Bezpartyjny Blok Współpracy z Rządem, czyli partię Piłsudskiego. Bardzo wielu Żydów głosowało też na partie syjonistyczne.

Polska Ludowa

W powojennej Polsce bardzo powszechne było przekonanie, że komunizm wprowadzany jest przez Żydów, choć polska społeczność żydowska w zasadzie przestała istnieć. Na czele państwa od 1945 roku stał "triumwirat", jak to określa Śpiewak - Bolesław Bierut i dwie osoby pochodzenia żydowskiego - Jakub Berman i Hilary Minc. W Komitecie Centralnym PZPR w tym czasie udział Żydów wynosił 6 proc.Jeżeli chodzi o zaangażowanie Żydów w służby bezpieczeństwa to Śpiewak podaje, że w latach 1944-1945 na 450 osób pełniących najwyższe funkcje w Ministerstwie Bezpieczeństwa Publicznego (od naczelnika wydziału wzwyż) 167 (37 proc.) było pochodzenia żydowskiego. Im niżej w strukturach UB, tym procent osób narodowości żydowskiej był niższy. Ryszard Terlecki podaje, że w 1945 roku 95 proc. funkcjonariuszy UB było narodowości polskiej, a Żydów było ok. 2,5 proc. Jednak to Żydzi zasiadali na najbardziej widocznych stanowiskach. Do czarnej legendy przeszły w Polsce osoby Józefa Różańskiego, Józefa Światły, Anatola Fejgina, Julii Brystiger, znaczący i widoczny był udział Żydów w aparacie propagandy, prasie i kulturze. W cenzurze stanowili oni 50 proc. pracowników.

W powojennej Polsce bardzo powszechne było przekonanie, że komunizm wprowadzany jest przez Żydów, choć polska społeczność żydowska w zasadzie przestała istnieć. Na czele państwa od 1945 roku stał "triumwirat", jak to określa Śpiewak - Bolesław Bierut i dwie osoby pochodzenia żydowskiego - Jakub Berman i Hilary Minc. W Komitecie Centralnym PZPR w tym czasie udział Żydów wynosił 6 proc.Pierwsze lata powojenne określa Śpiewak jako najlepszy okres w historii polskich Żydów - uzyskali oni równouprawnienie w dostępie do władzy. Jednak rychło w partii także zaczęły być widoczne odruchy antysemityzmu. Tuż przed śmiercią Stalina w 1953 roku, widoczne były przygotowania do antysemickiej czystki w łonie patii radzieckiej, podobne nastroje pojawiły się w Polsce, ale śmierć dyktatora położyła im kres, jak się okazało - tylko na pewien czas.

W roku 1967, kiedy wybuchła wojna sześciodniowa z wojska polskiego wyrzucono wszystkich oficerów pochodzenia żydowskiego, a w PZPR rozpoczęły się walki frakcyjne, wykorzystujące antysemityzm jako broń. Rok później antysemicka kampania szalała już w całym kraju, tysiące Żydów straciło pracę, kilkanaście tysięcy wyemigrowało z Polski. Wielu komunistycznych Żydów mogło się w tym okresie zgodzić ze starym, żydowskim przysłowiem "tańczyliśmy na nie swoim weselu" - pisze dyrektor ŻIH.

Śpiewak uważa, że pojęcie "żydokomuny" jest kluczowe dla zrozumienia losu Żydów w XX wieku - bez niego nie można zrozumieć Holokaustu, nie można zrozumieć przed i powojennego antysemityzmu w Polsce. Za zaangażowanie w komunizm niewielkiej części Żydów cały żydowski naród zapłacił straszną cenę - podsumowuje dyrektor ŻIH.

Książka "Żydokomuna. Interpretacje historyczne" ukazała się nakładem wydawnictwa Czerwone i Czarne.

Agata Szwedowicz (PAP)

aszw/ ls/

http://dzieje.pl/ksiazka/zydokomuna

Śpiewak: Mit żydokomuny jest ciągle w Polsce żywy

"Mit żydokomuny jest w Polsce ciągle żywy" - powiedział w środę na

spotkaniu z czytelnikami Paweł Śpiewak, przywołując słowa Jarosława

Kaczyńskiego i Jarosława Rymkiewicza o tym, że "Gazeta Wyborcza" jest

spadkobiercą Komunistycznej Partii Polski.

"Zarówno wypowiedzi Jarosława Kaczyńskiego, jak i Jarosława Rymkiewicza

sugerujące, że +Gazeta Wyborcza+ to spadkobiercy KPP, którzy propagują

ideologię luksemburgizmu, świadczą o tym, że mit żydokomuny jest w

Polsce ciągle żywy. Obaj w gruncie rzeczy przywołują ten termin, choć

nie wprost. To dowód na to, że mit żydokomuny nadal pojawia się w

różnych przebraniach, jest obecny w dyskursie publicznym, w grze

politycznej" - mówił Paweł Śpiewak, dyrektor Żydowskiego Instytutu

Historycznego, podczas środowej promocji swojej najnowszej książki

"Żydokomuna. Interpretacje historyczne".

Śpiewak podkreśla w swojej książce, że żydokomuna to nie realne zjawisko, lecz ideologiczny mit, w którym zbiegły się wszystkie antysemickie stereotypy z wielowiekowej tradycji oskarżania Żydów o wszelkie dziejące się zło. Zdaniem Śpiewaka termin "żydokomuna" daje możliwość głoszenia twierdzeń, że wszyscy Żydzi są nosicielami wrogiej ideologii, czyli bolszewizmu.

Śpiewak powiedział, że pracując nad "Żydokomuną" wzorował się na sposobie pisania książek historycznych przez innego socjologa - Jana Tomasza Grossa. "Nie ze wszystkimi stawianymi przez niego tezami się zgadzam, ale odpowiada mi jego sposób prowadzenia narracji. To historia, ale historia intelektualnie przetworzona, nie tylko suche fakty, ale próba ich interpretacji, odczytania. Sposób pisania Grossa jest dla mnie wzorcem" - powiedział Śpiewak.

W książce Śpiewak wielokrotnie podkreśla, że atrakcyjność ideologii komunistycznej dla Żydów wynikała z ograniczeń, jakim podlegali. To rewolucja po raz pierwszy w historii dała rosyjskim Żydom pełnię swobód obywatelskich oraz możliwość pracy w administracji. Także w II Rzeczpospolitej obowiązywało niepisane prawo ograniczające dostęp ludności żydowskiej do stanowisk w administracji, wojsku, szkolnictwie, na niektórych uczelniach obowiązywało getto ławkowe i numerus clausus. Śpiewak zauważa, że w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym młodzi, aspirujący do wyjścia z religijnego getta Żydzi nie mieli atrakcyjniejszej propozycji niż proklamujące równość społeczną ruchy lewicowe.

Jak podaje Śpiewak, do Komunistycznej Partii Polski w 1933 roku należało 8 tys. osób z czego 80 proc. stanowili Polacy, a około 20 proc. Żydzi. Przedwojenny Związek Młodzieży Komunistycznej Polski, liczący w połowie lat 30. niemal 12 tys. członków, w 42 proc. składał się z osób pochodzenia żydowskiego. Sami komuniści zauważali, że Żydzi są w KPP nadreprezentowani. W materiałach z 1929 roku znalazły się dane, że "towarzysze żydowscy w miastach stanowią przeważnie ponad 50 proc. składu organizacji, a są miasteczka, w których organizacja jest czysto żydowska". Proporcje narodowościowe przechylały się na korzyść Żydów w zarządzie partii. W styczniu 1936 roku na 30 członków Komitetu Centralnego KPP było 15 Polaków, 12 Żydów, 2 Ukraińców i 1 Białorusin.

Wobec faktu, że Żydzi stanowili ok. 10 proc. przedwojennej ludności Polski, można z tych liczb wyciągnąć wniosek o nadreprezantacji Żydów w strukturach komunistycznych. Śpiewak jednak zwraca uwagę, że ogromna większość polskich Żydów nie chciała mieć z komunizmem nic wspólnego. Na KPP głosowało w 1928 roku 7 proc. społeczności żydowskiej, a 50 proc. polskich Żydów oddało głosy na Bezpartyjny Blok Współpracy z Rządem, czyli partię Piłsudskiego. Bardzo wielu Żydów głosowało też na partie syjonistyczne.

W powojennej Polsce bardzo powszechne było przekonanie, że komunizm wprowadzany jest przez Żydów, choć polska społeczność żydowska w zasadzie przestała istnieć. Na czele państwa od 1945 roku stał "triumwirat", jak to określa Śpiewak: Bolesław Bierut i dwie osoby pochodzenia żydowskiego - Jakub Berman i Hilary Minc. W Komitecie Centralnym PZPR w tym czasie udział Żydów wynosił 6 proc.

"Po 20 latach niepodległości poza nielicznymi przypadkami nie doczekaliśmy się żadnych poważnych opracowań na temat ruchu komunistycznego w Polsce w jego różnych wymiarach. (...) Traktuję to, co napisałem, jako pewien etap badań. Na pewno jest potrzeba ich kontynuowania i mam nadzieję, że tak się stanie" - podsumował Śpiewak.

Książka "Żydokomuna. Interpretacje historyczne" ukazała się nakładem wydawnictwa Czerwone i Czarne. (PAP)

aszw/ hes/

Śpiewak podkreśla w swojej książce, że żydokomuna to nie realne zjawisko, lecz ideologiczny mit, w którym zbiegły się wszystkie antysemickie stereotypy z wielowiekowej tradycji oskarżania Żydów o wszelkie dziejące się zło. Zdaniem Śpiewaka termin "żydokomuna" daje możliwość głoszenia twierdzeń, że wszyscy Żydzi są nosicielami wrogiej ideologii, czyli bolszewizmu.

"Zarówno wypowiedzi Jarosława Kaczyńskiego, jak i Jarosława Rymkiewicza sugerujące, że +Gazeta Wyborcza+ to spadkobiercy KPP, którzy propagują ideologię luksemburgizmu, świadczą o tym, że mit żydokomuny jest w Polsce ciągle żywy. Obaj w gruncie rzeczy przywołują ten termin, choć nie wprost. To dowód na to, że mit żydokomuny nadal pojawia się w różnych przebraniach, jest obecny w dyskursie publicznym, w grze politycznej" - mówił Paweł Śpiewak."Zdaję sobie sprawę, że moja praca jest książką wysokiego ryzyka. Temat żydokomuny jest wciąż gorący, wzbudza wielkie emocje. Wiem, że narażam się antysemitom, ale do tego, że oni istnieją, już się przyzwyczaiłem" - mówił Śpiewak dodając, że jego książka może też nie wzbudzić entuzjazmu środowisk, które "psychologicznie, ideowo mają poczucie jakiegoś związku z tamtym pokoleniem, żydowskich komunistów".

Śpiewak powiedział, że pracując nad "Żydokomuną" wzorował się na sposobie pisania książek historycznych przez innego socjologa - Jana Tomasza Grossa. "Nie ze wszystkimi stawianymi przez niego tezami się zgadzam, ale odpowiada mi jego sposób prowadzenia narracji. To historia, ale historia intelektualnie przetworzona, nie tylko suche fakty, ale próba ich interpretacji, odczytania. Sposób pisania Grossa jest dla mnie wzorcem" - powiedział Śpiewak.

W książce Śpiewak wielokrotnie podkreśla, że atrakcyjność ideologii komunistycznej dla Żydów wynikała z ograniczeń, jakim podlegali. To rewolucja po raz pierwszy w historii dała rosyjskim Żydom pełnię swobód obywatelskich oraz możliwość pracy w administracji. Także w II Rzeczpospolitej obowiązywało niepisane prawo ograniczające dostęp ludności żydowskiej do stanowisk w administracji, wojsku, szkolnictwie, na niektórych uczelniach obowiązywało getto ławkowe i numerus clausus. Śpiewak zauważa, że w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym młodzi, aspirujący do wyjścia z religijnego getta Żydzi nie mieli atrakcyjniejszej propozycji niż proklamujące równość społeczną ruchy lewicowe.

Jak podaje Śpiewak, do Komunistycznej Partii Polski w 1933 roku należało 8 tys. osób z czego 80 proc. stanowili Polacy, a około 20 proc. Żydzi. Przedwojenny Związek Młodzieży Komunistycznej Polski, liczący w połowie lat 30. niemal 12 tys. członków, w 42 proc. składał się z osób pochodzenia żydowskiego. Sami komuniści zauważali, że Żydzi są w KPP nadreprezentowani. W materiałach z 1929 roku znalazły się dane, że "towarzysze żydowscy w miastach stanowią przeważnie ponad 50 proc. składu organizacji, a są miasteczka, w których organizacja jest czysto żydowska". Proporcje narodowościowe przechylały się na korzyść Żydów w zarządzie partii. W styczniu 1936 roku na 30 członków Komitetu Centralnego KPP było 15 Polaków, 12 Żydów, 2 Ukraińców i 1 Białorusin.

Wobec faktu, że Żydzi stanowili ok. 10 proc. przedwojennej ludności Polski, można z tych liczb wyciągnąć wniosek o nadreprezantacji Żydów w strukturach komunistycznych. Śpiewak jednak zwraca uwagę, że ogromna większość polskich Żydów nie chciała mieć z komunizmem nic wspólnego. Na KPP głosowało w 1928 roku 7 proc. społeczności żydowskiej, a 50 proc. polskich Żydów oddało głosy na Bezpartyjny Blok Współpracy z Rządem, czyli partię Piłsudskiego. Bardzo wielu Żydów głosowało też na partie syjonistyczne.

W powojennej Polsce bardzo powszechne było przekonanie, że komunizm wprowadzany jest przez Żydów, choć polska społeczność żydowska w zasadzie przestała istnieć. Na czele państwa od 1945 roku stał "triumwirat", jak to określa Śpiewak: Bolesław Bierut i dwie osoby pochodzenia żydowskiego - Jakub Berman i Hilary Minc. W Komitecie Centralnym PZPR w tym czasie udział Żydów wynosił 6 proc.

W powojennej Polsce bardzo powszechne było przekonanie, że komunizm wprowadzany jest przez Żydów, choć polska społeczność żydowska w zasadzie przestała istnieć. Na czele państwa od 1945 roku stał "triumwirat", jak to określa Śpiewak: Bolesław Bierut i dwie osoby pochodzenia żydowskiego - Jakub Berman i Hilary Minc. W Komitecie Centralnym PZPR w tym czasie udział Żydów wynosił 6 proc.Śpiewak podaje, że w latach 1944-1945 na 450 osób pełniących najwyższe funkcje w Ministerstwie Bezpieczeństwa Publicznego (od naczelnika wydziału wzwyż) 167 (37 proc.) było pochodzenia żydowskiego. Im niżej w strukturach UB, tym procent osób narodowości żydowskiej był niższy. Śpiewak cytuje Ryszarda Terleckiego, który podaje, że w 1945 roku 95 proc. funkcjonariuszy UB było narodowości polskiej, a Żydów było ok. 2,5 proc. Jednak to Żydzi zasiadali na najbardziej widocznych stanowiskach.

"Po 20 latach niepodległości poza nielicznymi przypadkami nie doczekaliśmy się żadnych poważnych opracowań na temat ruchu komunistycznego w Polsce w jego różnych wymiarach. (...) Traktuję to, co napisałem, jako pewien etap badań. Na pewno jest potrzeba ich kontynuowania i mam nadzieję, że tak się stanie" - podsumował Śpiewak.

Książka "Żydokomuna. Interpretacje historyczne" ukazała się nakładem wydawnictwa Czerwone i Czarne. (PAP)

aszw/ hes/

ŻYD JAKO WRÓG POLSKI

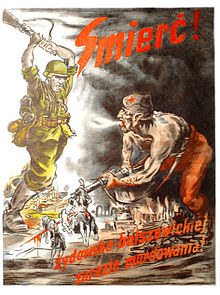

Antysemickie rysunki z polskiej prasy

okresu II RP, przedstawiające Żydów m.in. jako istoty demoniczne,

zaprezentuje wystawa „Obcy i niemili”, której wernisaż odbędzie się we

wtorek wieczorem w Żydowskim Instytucie Historycznym w Warszawie.

Otwarcie ekspozycji poprzedziła wtorkowa konferencja prasowa w ŻIH, z

udziałem twórców i organizatorów wystawy. Jak zgodnie podkreślili,

karykatury towarzyszące antysemickim artykułom z okresu międzywojennego

stanowiły istotny czynnik kształtowania odrażającego wizerunku Żyda,

wpływały na poglądy na temat mniejszości żydowskiej w II RP.

Dyrektor ŻIH prof. Paweł Śpiewak przypomniał, że w międzywojennej Polsce nastąpił okres rozwoju żydowskiej kultury, szkolnictwa, tworzenia przez Żydów partii politycznych; z drugiej jednak strony był to dla wyznawców religii mojżeszowej czas dramatyczny. „Bojkot Żydów, getta ławkowe i rysunki antysemickie w polskiej prasie tworzyły wokół Żydów atmosferę nienawiści” – wyjaśnił Śpiewak.

Wystawa składa się z trzech części. Pierwsza, zatytułowana „Oto Żyd”, prezentuje rysunki ukazujące Żydów we wszystkich jego wcieleniach. „Od przedstawień żydowskiego ciała, odbiegającego wyraźnie od normy człowieczeństwa (...), poprzez ilustracje wyobrażenia o tzw. żydowskiej mentalności, specyficznym żydowskim pomyślunku, aż po pokazanie Żydów jako osoby z natury swej zmaterializowane” – wyjaśnił kurator ekspozycji Dariusz Konstantynow.

Stereotypizacja Żydów w polskiej prasie lat 20. i 30. XX w. – tłumaczył Konstantynow – zmierzała do przypisania im cech demonicznych. „Żyd występuje tu jako diabeł wcielony” – zwrócił uwagę kurator.

Druga część wystawy, nazwana „Tam, gdzie mniejszość jest większością”, poświęcona jest wyobrażeniom o roli mniejszości żydowskiej w II RP. „Najogólniej mówiąc, Żyd we wszystkich tych rysunkach występuje jako wróg (...). Jest wrogiem, kiedy jest komunistą i bolszewikiem; jest wrogiem, gdy jest wyzyskiwaczem i kapitalistą” – wyjaśnił Konstantynow. Zaznaczył, że żydowska mniejszość została ukazana jako społeczność agresywna, dążąca do rozciągnięcia swych zgubnych wpływów na całą Polskę.

Trzecia część ekspozycji – „Co zrobić z Żydami?” – przybliża obecne na łamach antysemickiej prasy sposoby rozwiązania tzw. kwestii żydowskiej. Na rysunkach przedstawiono rozmaite kierunki emigracji Żydów z Polski; doceniono także nazistów, którzy podjęli „trud” rozprawienia się z Żydami w swym kraju.

Zaprezentowane na wystawie prace były publikowane w okresie międzywojennym na łamach m.in.: „Kuriera Poznańskiego”, „Dziennika Bydgoskiego”, „ABC-Nowin Codziennych”, „Wieczoru Warszawskiego”, „Podbipięty”, „Prosto z mostu”, „Szczutka”, „Szopki”, „Muchy”, „Żółtej Muchy”, „Szarży”, „Pokrzyw” i „Szabes-Kuriera”.

Autorzy rysunków to zarówno znani artyści profesjonalni (m.in. Jerzy Zaruba, Kamil Mackiewicz, Włodzimierz Bartoszewicz, Włodzimierz Łukasik, Jerzy Srokowski, Kazimierz Grus i Maja Berezowska), jak i anonimowi, podpisujący się monogramami i pseudonimami.

Oprócz obejrzenia antysemickich rysunków, zwiedzający wystawę będą mogli zobaczyć film o mowie nienawiści, w którym głos zabrali m.in. profesorowie: Jerzy Bralczyk i Michał Głowiński.

Organizatorem ekspozycji „+Obcy i niemili+. Antysemickie rysunki z prasy polskiej 1919–1939” jest Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuela Ringelbluma w Warszawie.

Patronat medialny nad wystawą, która potrwa do końca stycznia 2014 r., sprawuje m.in. portal historyczny dzieje.pl, prowadzony przez Polską Agencję Prasową i Muzeum Historii Polski. (PAP)

wmk/ abe/

http://dzieje.pl/wystawy/antysemickie-rysunki-w-polskiej-prasie-w-okresie-ii-rp-wystawa-w-zih

Żydokomuna ([ʐɨdɔkɔˈmuna], "Judeo-Communism")[1][2] is a pejorative term for an antisemitic canard[3] that refers to alleged Jewish–Soviet collaboration in importing communism into Poland,[4] where communism was sometimes identified as part of a wider Jewish-led conspiracy to seize power.[5] Historians dispute the claims of Żydokomuna.

The idea of Żydokomuna continued to endure to a certain extent in postwar Poland (1944–1956),[6] because Polish anti-communists saw the Soviet-controlled Communist regime as the fruition of prewar anti-Polish agitation; with it came the implication of Jewish responsibility. The Soviet appointments of Jews to positions responsible for oppressing the populace further fueled this perception.[7][8] Some 37.1% of post-war management of UB employees and members of the communist authorities in Poland were of Jewish origin. They were described in intelligence reports as very loyal to the Soviets (Szwagrzyk).[6] Some Polish historians have impugned the loyalty of Jews returning to Poland from the USSR after the Soviet takeover, which has raised the specter of Żydokomuna in the minds of other scholars.[9]

At the end of the 19th century, Roman Dmowski's National Democratic party characterized Poland's Jews and other opponents of Dmowski's party as internal enemies who were behind international conspiracies inimical to Poland and who were agents of disorder, disruption and socialism.[13][14] Historian Antony Polonsky writes that before World War I "The National Democrats brought to Poland a new and dangerous ideological fanaticism, dividing society into 'friends' and 'enemies' and resorting constantly to conspiratorial theories ("Jewish-Masonic plot"; "Żydokomuna"—"Jew-communism") to explain Poland's difficulties."[15] Meanwhile, Jews played into National Democratic rhetoric by affirming themselves as alien through their participation in exclusively Jewish organizations such as the Bund and the Zionist movement.[13]

The term Żydokomuna originated in connection with the Russian Bolshevik Revolution and targeted Jewish communists during the Polish-Soviet War. The emergence of the Soviet state was seen by many Poles as Russian imperialism in a new guise.[12] The visibility of Jews in both the Soviet leadership and in the Polish Communist Party further heightened such fears.[12] In some circles, Żydokomuna came to be seen as a prominent antisemitic stereotype[16] expressing political paranoia.[12]

Accusations of Żydokomuna accompanied the incidents of anti-Jewish violence in Poland during Polish–Soviet War of 1920, legitimized as self-defense against a people who were oppressors of the Polish nation. Some soldiers and officers in the Polish eastern territories shared the conviction that Jews were enemies of the Polish nation-state and were collaborators with Poland's enemies. Some of these troops treated all Jews as Bolsheviks. According to some sources, anticommunist sentiment was implicated in anti-Jewish violence and killings in a number of towns, including the Pinsk massacre, in which 35 Jews, taken as hostages, were murdered, and the Lwów pogrom during the Polish-Ukrainian War, in which 72 Jews were killed. Occasional instances of Jewish support for Bolshevism during the Polish-Soviet War served to heighten anti-Jewish sentiment.[17][18]

The concept of Żydokomuna was widely illustrated in Polish interwar politics, including publications by the National Democrats[19] and the Catholic Church that expressed anti-Jewish views.[20][21][22] During World War II, the term Żydokomuna was made to resemble the Jewish-Bolshevism rhetoric of Nazi Germany, wartime Romania[23] and other war-torn countries of Central and Eastern Europe.[24]

The National Democrats (Endeks) emerged from the 1930 Polish elections to Sejm as the main opposition party to the Piłsudski government. Piłsudski had a liberal attitude towards minorities, and was respected by much of the Polish Jewish minority.[25] In the midst of the Great Depression and in a climate of widespread nationalist and antisemitic sentiment, the Endeks expressed anti-Jewish sentiment to show their dissatisfaction with the government. The Endeks

called for reducing the numbers of Jews in the country and for an

economic boycott (launched in 1931); subsequently, outbreaks of violence

occurred against Jews, particularly at universities. Following the

death of Piłsudski in 1935, the Endeks moved towards seizing power in Poland, and began to focus more fully on the Jews. While there was a limited audience for Endek

rhetoric, it was supplemented by the much larger circulation enjoyed by

Catholic Church publications, which increasingly referred to the

communist threat and the alleged "Godlessness" of the Jews. One such

Church publication, the newspaper Samoobrona Narodu ("Self-Defense of the Nation," which meant defense against Jews), had a circulation of over one million.[26]

In the period between the two world wars, Żydokomuna sentiment grew concurrently in Poland with the notion of the "criminal Jew."[27] Statistics from the 1920s had indicated a Jewish crime rate that was well below the percentage of Jews in the population. However, a subsequent reclassification of how crime was recorded—which now included minor offenses—succeeded in reversing the trend, and Jewish criminal statistics showed an increase relative to the Jewish population by the 1930s. These statistics were seen by some Poles, particularly within the right-wing press, to confirm the image of the "criminal Jew"; additionally, political crimes by Jews were more closely scrutinized, enhancing fears of a criminal Żydokomuna.[27]

Another important factor was the dominance of Jews in the leadership of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP). According to multiple sources, Jews were well represented in the Polish Communist Party.[21][28] Notably, the party had strong Jewish representation at higher levels. Out of fifteen leaders of the KPP central administration in 1936, eight were Jews. Jews constituted 53% of the "active members" of the KPP, 75% of its "publication apparatus," 90% of the "international department for help to revolutionaries" and 100% of the "technical apparatus" of the Home Secretariat. In Polish court proceedings against communists between 1927 and 1936, 90% of the accused were Jews. In terms of membership, before its dissolution in 1938, 25% of KPP members were Jews; most urban KPP members were Jews—a substantial number, given an 8.7% Jewish minority in prewar Poland.[29] Some historians, including Joseph Marcus, qualify these statistics, alleging that the KPP should not be considered a "Jewish party," as it was in fact in opposition to traditional Jewish economic and national interests.[30] The Jews supporting KPP saw themselves as international communists and rejected much of the Jewish culture and tradition.[31] Nonetheless, the KPP, along with the Polish Socialist Party, was notable for its decisive stand against antisemitism.[32] According to Jaff Schatz's summary of Jewish participation in the prewar Polish communist movement:

According to some sources, the Poles resented their change of fortunes because, before the war, Poles had a privileged position. Then, in the space of a few days, Jews and other minorities from within Poland occupied positions in the Soviet occupation government—such as teachers, civil servants and engineers—that they allegedly had trouble achieving under the Polish government.[46][47] What to the majority of Poles was occupation and betrayal was, to some Jews—especially Polish communists of Jewish descent who emerged from the underground—an opportunity for revolution and retribution. There were even some extreme cases of Jewish participation in massacres of ethnic Poles such as Massacre of Brzostowica Mała.[47][48] Such behavior affronted non-Jewish Poles.

Such events implanted in the Polish collective memory the image of Jewish crowds greeting the invading Red Army as liberators, and willing collaborators,[40] further strengthening Żydokomuna sentiment that held Jews responsible for collaboration with the Soviet authorities in importing communism into divided Poland.[47][49][50] After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, widespread notion of Judeo-Communism, combined with the German Nazi encouragement for expression of antisemitic attitudes, may have been a principal cause of massacres of Jews by gentile Poles in Poland's northeastern Łomża province in the summer of 1941, including the massacre at Jedwabne according to Joanna B. Michlic.[51] However, the responsibility of the gentile Poles for the Jedwabne pogrom has been highly disputed, with some sources stating that the Germans were the principal authors of the massacre.

Though some Jews had initially benefited from the effects of the Soviet invasion, this occupation soon began to strike at the Jewish population as well; independent Jewish organizations were abolished and Jewish activists were arrested. Hundreds of thousands of Jews who had fled to the Soviet sector were given a choice of Soviet citizenship or returning to the German occupied zone. The majority chose the latter, and instead found themselves deported to the Soviet Union, where, ironically, 300,000 would escape the Holocaust.[47][52] While there was Polish Jewish representation in the London-based Polish government in exile, relations between the Jews in Poland and Polish resistance in occupied Poland were strained, and Jewish armed groups had difficulty joining the official Polish resistance umbrella organization, the Home Army (in Polish, Armia Krajowa or AK).[53][54] Some Jewish groups (such as the Bielski partisans) robbed local Polish peasants for food, also performing massacres and crimes like Naliboki massacre in 1943 ; in turn, the Polish underground often labeled those armed Jewish groups as "bandits" and "robbers."[55] Jewish partisans instead more often joined the Armia Ludowa of the communist Polish Workers' Party[55][56] and Soviet guerrilla groups, which increasingly clashed with Polish guerillas, contributing to yet another perception of Jews working with the Soviets against the Poles.[47]

Hilary Minc, the third in command in Bolesław Bierut's political triumvirate of Stalinist leaders,[60] became the Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Industry, Industry and Commerce, and the Economic Affairs. He was personally assigned by Stalin first to Industry and than to Transportation ministries of Poland.[61] His wife, Julia, became the Editor-in-Chief of the monopolized Polish Press Agency. Minister Jakub Berman – Stalin's right hand in Poland until 1953 – held the Political propaganda and Ideology portfolios. He was responsible for the largest and most notorious secret police in the history of the People's Republic of Poland, the Ministry of Public Security (UB), employing 33,200 permanent security officers, one for every 800 Polish citizens.[60]

The new government's hostility to the wartime Polish Government in Exile and its World War II underground resistance – accused by the media of being nationalist, reactionary and antisemitic, and persecuted by Berman – further strengthened Żydokomuna sentiment to the point where in the popular consciousness Jewish Bolshevism was seen as having conquered Poland.[59] It was in this context, reinforced by the immediate post-war lawlessness, that Poland experienced an unprecedented wave of anti-Jewish violence (of which most notable was the Kielce pogrom).[62]

The Polish-American historian Marek Jan Chodakiewicz stressed that after the Soviet takeover of Poland in 1945 violence had developed amid postwar retribution and counter-retribution, exacerbated by the breakdown of law and order and a Polish anti-Communist insurgency.[63] According to Chodakiewicz, some Jewish "avengers" endeavored to extract justice from the Poles who harmed Jews during the War and in some cases Jews attempted to reclaim property confiscated by the Nazis. These phenomena further reinforced Żydokomuna sentiment. Chodakiewicz noted that after World War II, the Jews were not only victims, but also aggressors. He describes cases in which Jews cooperated with the Polish secret police, denouncing Poles and members of the Home Army. Chodakiewicz noted that some 3,500 to 6,500 Poles died in late 1940s because of Jewish denunciations or were killed by Jews themselves.[64] Encouraged by their Soviet advisors, many Jewish functionaries and government officials adopted new Polish-sounding names hoping to find less acrimony among their adversaries. "This practice often backfired and led to widespread speculation about 'hidden Jews' for decades to come."[65]

The combination of the effects of the Holocaust and postwar antisemitism led to a dramatic mass emigration of Polish Jewry in the immediate postwar years. Of the estimated 240,000 Jews in Poland in 1946 (of whom 136,000 were refugees from the Soviet Union, most on their way to the West), only 90,000 remained a year later.[66][67] The surviving Jews of Poland found themselves victims of the explosive postwar political situation. The image of the Jew as a threatening outsider took on a new form as antisemitism was now linked to the imposition of communist rule in Poland, including rumors of massive collaboration of Jews with the unpopular new regime and the Soviet Union. Of the fewer than 80,000 Jews who remained in Poland, many had political reasons for doing so. Consequently, – as noted by historian Michael C. Steinlauf – "their group profile ever more closely resembled the Żydokomuna."[68][69] Regarding this period, Andre Gerrits wrote in his study of Żydokomuna, that even though for the first time in history they had entered the top echelons of power in considerable numbers, "The first post-war decade was a mixed experience for the Jews of East Central Europe. The new communist order offered unprecedented opportunities as well as unforeseen dangers."[70]

In 1956, over 9,000 socialist and populist politicians were released from prison.[76] A few Jewish functionaries of the security forces were brought to court in the process of de-Stalinization. According to Heather Laskey, it was not a coincidence that the high ranking Stalinist security officers put on trial by Gomułka were Jews.[77] Władysław Gomułka was captured by Światło, imprisoned by Romkowski in 1951 and interrogated by both, him and Fejgin. Gomułka escaped physical torture only as a close associate of Joseph Stalin,[78] and was released three years later.[79] According to some sources, the categorization of the security forces as a Jewish institution—as disseminated in the post-war anticommunist press at various times—was rooted in Żydokomuna: the belief that the secret police was predominantly Jewish became one of the factors contributing to the post-war view of Jews as agents of the security forces.[80]

The Żydokomuna sentiment reappeared at times of severe political and socioeconomic crises in Stalinist Poland. After the death of Polish United Workers' Party leader Bolesław Bierut in 1956, a de-Stalinization and a subsequent battle among rival factions looked to lay blame for the excesses of the Stalin era. According to L.W. Gluchowski: "Poland’s communists had grown accustomed to placing the burden of their own failures to gain sufficient legitimacy among the Polish population during the entire communist period on the shoulders of Jews in the party."[73] (See: above.) As described in one historical account, the party hardline Natolin faction "used anti-Semitism as a political weapon and found an echo both in the party apparatus and in society at large, where traditional stereotypes of an insidious Jewish cobweb of political influence and economic gain resurfaced, but now in the context of 'Judeo-communism,' the Żydokomuna."[81] "Natolin" leader Zenon Nowak entered the concept of "Judeo-Stalinization" and placed the blame for the party's failures, errors and repression on "the Jewish apparatchiks." Documents from this period chronicle antisemitic attitudes within Polish society, including beatings of Jews, loss of employment, and persecution. These outbursts of antisemitic sentiment from both Polish society and within the rank and file of the ruling party spurred the exodus of some 40,000 Polish Jews between 1956 and 1958.[82][83]

The campaign, which began in 1967, was a well-guided response to the Six-Day War and the subsequent break-off by the Soviets of all diplomatic relations with Israel. Polish factory workers were forced to publicly denounce Zionism. As the interior minister Mieczysław Moczar's nationalist "Partisan" faction became increasingly influential in the communist party, infighting within the Polish communist party led one faction to again make scapegoats of the remaining Polish Jews, attempting to redirect public anger at them. After Israel's victory in the war, the Polish government, following the Soviet lead, launched an antisemitic campaign under the guise of "anti-Zionism," with both Moczar's and Party Secretary Władysław Gomułka's factions playing leading roles. However, the campaign did not resonate with the general public, because most Poles saw similarities between Israel's fight for survival and Poland's past struggles for independence. Many Poles felt pride in the success of the Israeli military, which was dominated by Polish Jews. The slogan, "Our Jews beat the Soviet Arabs"[88] was very popular among the Poles, but contrary to the desire of the communist government.[89]

The government's antisemitic policy yielded more successes the next year. In March 1968, a wave of unrest among students and intellectuals, unrelated to the Arab-Israeli War, swept Poland (the events became known as the March 1968 events). The campaign served multiple purposes, most notably the suppression of protests, which were branded as inspired by a "fifth column" of Zionists; it was also used as a tactic in a political struggle between Gomułka and Moczar, both of whom played the Jewish card in a nationalist appeal.[87][90][91] The campaign resulted in an actual expulsion from Poland in two years, of thousands of Jewish professionals, party officials and state security functionaries. Ironically, the Moczar's faction failed to topple Gomułka with their propaganda efforts.[92]

As historian Dariusz Stola notes, the anti-Jewish campaign combined century-old conspiracy theories, recycled antisemitic claims and classic communist propaganda. Regarding the tailoring of the Żydokomuna sentiment to communist Poland, Stola suggested:

Stola also notes that one of the effects of the 1968 antisemitic campaign was to thoroughly discredit the communist government in the eyes of the public. As a result, when the concept of the Jew as a "threatening other" was employed in the 1970s and 1980s in Poland by the communist government in its attacks on the political opposition, including the Solidarity trade-union movement and the Workers' Defence Committee (Komitet Obrony Robotników, or KOR), it was completely unsuccessful.[87]

Historian Omer Bartov has written that "recent writings and pronouncements seem to indicate that the myth of the Żydokomuna (Jews as communists) has not gone away" as evidenced by the writings of younger Polish scholars such as Marek Chodakiewicz, contending Jewish disloyalty to Poland during the Soviet occupation.[9] Historians Joanna B. Michlic and Laurence Weinbaum charge that post-1989 Polish historiography has seen a revival of "an ethnonationalist historical approach".[97][103] According to Michlic, among some Polish historians, "[myth of żydokomuna] served the purpose of rationalizing and explaining the participation of ethnic Poles in killing their Jewish neighbors and, thus, in minimizing the criminal nature of the murder."[97][104]

Dyrektor ŻIH prof. Paweł Śpiewak przypomniał, że w międzywojennej Polsce nastąpił okres rozwoju żydowskiej kultury, szkolnictwa, tworzenia przez Żydów partii politycznych; z drugiej jednak strony był to dla wyznawców religii mojżeszowej czas dramatyczny. „Bojkot Żydów, getta ławkowe i rysunki antysemickie w polskiej prasie tworzyły wokół Żydów atmosferę nienawiści” – wyjaśnił Śpiewak.

Dyrektor ŻIH prof. Paweł Śpiewak przypomniał, że w międzywojennej Polsce nastąpił okres rozwoju żydowskiej kultury, szkolnictwa, tworzenia przez Żydów partii politycznych; z drugiej jednak strony był to dla wyznawców religii mojżeszowej czas dramatyczny. „Bojkot Żydów, getta ławkowe i rysunki antysemickie w polskiej prasie tworzyły wokół Żydów atmosferę nienawiści” – wyjaśnił Śpiewak.Jak dodał, przedstawianie w polskiej prasie Żydów jako zdeformowane istoty przypominające zwierzęta, a nawet robactwo, sprzyjało powstawaniu dystansu między Polakami i Żydami, który wywoływał obojętność w czasie Holokaustu.

Wystawa składa się z trzech części. Pierwsza, zatytułowana „Oto Żyd”, prezentuje rysunki ukazujące Żydów we wszystkich jego wcieleniach. „Od przedstawień żydowskiego ciała, odbiegającego wyraźnie od normy człowieczeństwa (...), poprzez ilustracje wyobrażenia o tzw. żydowskiej mentalności, specyficznym żydowskim pomyślunku, aż po pokazanie Żydów jako osoby z natury swej zmaterializowane” – wyjaśnił kurator ekspozycji Dariusz Konstantynow.

Stereotypizacja Żydów w polskiej prasie lat 20. i 30. XX w. – tłumaczył Konstantynow – zmierzała do przypisania im cech demonicznych. „Żyd występuje tu jako diabeł wcielony” – zwrócił uwagę kurator.

Druga część wystawy, nazwana „Tam, gdzie mniejszość jest większością”, poświęcona jest wyobrażeniom o roli mniejszości żydowskiej w II RP. „Najogólniej mówiąc, Żyd we wszystkich tych rysunkach występuje jako wróg (...). Jest wrogiem, kiedy jest komunistą i bolszewikiem; jest wrogiem, gdy jest wyzyskiwaczem i kapitalistą” – wyjaśnił Konstantynow. Zaznaczył, że żydowska mniejszość została ukazana jako społeczność agresywna, dążąca do rozciągnięcia swych zgubnych wpływów na całą Polskę.

Trzecia część ekspozycji – „Co zrobić z Żydami?” – przybliża obecne na łamach antysemickiej prasy sposoby rozwiązania tzw. kwestii żydowskiej. Na rysunkach przedstawiono rozmaite kierunki emigracji Żydów z Polski; doceniono także nazistów, którzy podjęli „trud” rozprawienia się z Żydami w swym kraju.

Zaprezentowane na wystawie prace były publikowane w okresie międzywojennym na łamach m.in.: „Kuriera Poznańskiego”, „Dziennika Bydgoskiego”, „ABC-Nowin Codziennych”, „Wieczoru Warszawskiego”, „Podbipięty”, „Prosto z mostu”, „Szczutka”, „Szopki”, „Muchy”, „Żółtej Muchy”, „Szarży”, „Pokrzyw” i „Szabes-Kuriera”.

Autorzy rysunków to zarówno znani artyści profesjonalni (m.in. Jerzy Zaruba, Kamil Mackiewicz, Włodzimierz Bartoszewicz, Włodzimierz Łukasik, Jerzy Srokowski, Kazimierz Grus i Maja Berezowska), jak i anonimowi, podpisujący się monogramami i pseudonimami.

Oprócz obejrzenia antysemickich rysunków, zwiedzający wystawę będą mogli zobaczyć film o mowie nienawiści, w którym głos zabrali m.in. profesorowie: Jerzy Bralczyk i Michał Głowiński.

Organizatorem ekspozycji „+Obcy i niemili+. Antysemickie rysunki z prasy polskiej 1919–1939” jest Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuela Ringelbluma w Warszawie.

Patronat medialny nad wystawą, która potrwa do końca stycznia 2014 r., sprawuje m.in. portal historyczny dzieje.pl, prowadzony przez Polską Agencję Prasową i Muzeum Historii Polski. (PAP)

wmk/ abe/

http://dzieje.pl/wystawy/antysemickie-rysunki-w-polskiej-prasie-w-okresie-ii-rp-wystawa-w-zih

Żydokomuna

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Part of Jewish history

|

The idea of Żydokomuna continued to endure to a certain extent in postwar Poland (1944–1956),[6] because Polish anti-communists saw the Soviet-controlled Communist regime as the fruition of prewar anti-Polish agitation; with it came the implication of Jewish responsibility. The Soviet appointments of Jews to positions responsible for oppressing the populace further fueled this perception.[7][8] Some 37.1% of post-war management of UB employees and members of the communist authorities in Poland were of Jewish origin. They were described in intelligence reports as very loyal to the Soviets (Szwagrzyk).[6] Some Polish historians have impugned the loyalty of Jews returning to Poland from the USSR after the Soviet takeover, which has raised the specter of Żydokomuna in the minds of other scholars.[9]

Prelude

According to some sources, the concept of a Jewish conspiracy threatening Polish social order dates in print to the pamphlet Rok 3333 czyli sen niesłychany (The Year 3333, or the Incredible Dream) by Polish Enlightenment author and political activist Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, written in 1817 and published posthumously in 1858. Called "the first Polish work to develop on a large scale the concept of an organized Jewish conspiracy directly threatening the existing social structure,"[10][11][12] it describes a Warsaw of the future renamed Moszkopolis after its Jewish ruler.[12] (See "Judeopolonia" article for more.)At the end of the 19th century, Roman Dmowski's National Democratic party characterized Poland's Jews and other opponents of Dmowski's party as internal enemies who were behind international conspiracies inimical to Poland and who were agents of disorder, disruption and socialism.[13][14] Historian Antony Polonsky writes that before World War I "The National Democrats brought to Poland a new and dangerous ideological fanaticism, dividing society into 'friends' and 'enemies' and resorting constantly to conspiratorial theories ("Jewish-Masonic plot"; "Żydokomuna"—"Jew-communism") to explain Poland's difficulties."[15] Meanwhile, Jews played into National Democratic rhetoric by affirming themselves as alien through their participation in exclusively Jewish organizations such as the Bund and the Zionist movement.[13]

Origin

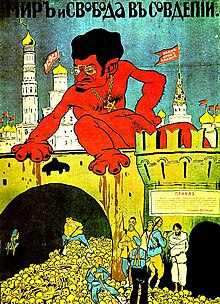

Limited-run Polish propaganda poster from the Polish-Soviet War (1920–1921), "Jewish Paws Again? Never!", targeted at Orthodox citizens of Poland in the eastern territories

Accusations of Żydokomuna accompanied the incidents of anti-Jewish violence in Poland during Polish–Soviet War of 1920, legitimized as self-defense against a people who were oppressors of the Polish nation. Some soldiers and officers in the Polish eastern territories shared the conviction that Jews were enemies of the Polish nation-state and were collaborators with Poland's enemies. Some of these troops treated all Jews as Bolsheviks. According to some sources, anticommunist sentiment was implicated in anti-Jewish violence and killings in a number of towns, including the Pinsk massacre, in which 35 Jews, taken as hostages, were murdered, and the Lwów pogrom during the Polish-Ukrainian War, in which 72 Jews were killed. Occasional instances of Jewish support for Bolshevism during the Polish-Soviet War served to heighten anti-Jewish sentiment.[17][18]

The concept of Żydokomuna was widely illustrated in Polish interwar politics, including publications by the National Democrats[19] and the Catholic Church that expressed anti-Jewish views.[20][21][22] During World War II, the term Żydokomuna was made to resemble the Jewish-Bolshevism rhetoric of Nazi Germany, wartime Romania[23] and other war-torn countries of Central and Eastern Europe.[24]

Interbellum

Polish anti-Bolshevik propaganda piece, 1920.

In the period between the two world wars, Żydokomuna sentiment grew concurrently in Poland with the notion of the "criminal Jew."[27] Statistics from the 1920s had indicated a Jewish crime rate that was well below the percentage of Jews in the population. However, a subsequent reclassification of how crime was recorded—which now included minor offenses—succeeded in reversing the trend, and Jewish criminal statistics showed an increase relative to the Jewish population by the 1930s. These statistics were seen by some Poles, particularly within the right-wing press, to confirm the image of the "criminal Jew"; additionally, political crimes by Jews were more closely scrutinized, enhancing fears of a criminal Żydokomuna.[27]

Another important factor was the dominance of Jews in the leadership of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP). According to multiple sources, Jews were well represented in the Polish Communist Party.[21][28] Notably, the party had strong Jewish representation at higher levels. Out of fifteen leaders of the KPP central administration in 1936, eight were Jews. Jews constituted 53% of the "active members" of the KPP, 75% of its "publication apparatus," 90% of the "international department for help to revolutionaries" and 100% of the "technical apparatus" of the Home Secretariat. In Polish court proceedings against communists between 1927 and 1936, 90% of the accused were Jews. In terms of membership, before its dissolution in 1938, 25% of KPP members were Jews; most urban KPP members were Jews—a substantial number, given an 8.7% Jewish minority in prewar Poland.[29] Some historians, including Joseph Marcus, qualify these statistics, alleging that the KPP should not be considered a "Jewish party," as it was in fact in opposition to traditional Jewish economic and national interests.[30] The Jews supporting KPP saw themselves as international communists and rejected much of the Jewish culture and tradition.[31] Nonetheless, the KPP, along with the Polish Socialist Party, was notable for its decisive stand against antisemitism.[32] According to Jaff Schatz's summary of Jewish participation in the prewar Polish communist movement:

Throughout the whole interwar period, Jews constituted a very important segment of the Communist movement. According to Polish sources and to Western estimates, the proportion of Jews in the KPP [the Communist Party of Poland] was never lower than 22 percent. In the larger cities, the percentage of Jews in the KPP often exceeded 50 percent and in smaller cities, frequently over 60 percent. Given this background, a respondent's statement that "in small cities like ours, almost all Communists were Jews," does not appear to be a gross exaggeration.[33]According to some bodies of research, voting patterns in Poland's parliamentary elections in the 1920s revealed that Jewish support for the communists was proportionally less than their representation in the total population.[34] In this view, most support for Poland's communist and pro-Soviet parties came not from Jews, but rather from Ukrainian and Orthodox Belarusian voters,[34] though some of these may have been of Jewish ancestry. Schatz notes that even if post-war claims by Jewish communists that 40% of the 266,528 communist votes on several lists of front organizations at the 1928 Sejm election came from the Jewish community were true (a claim that one source describes as "almost certainly an exaggeration"),[35] this would amount to no more than 5% of Jewish votes for the communists, indicating the Jewish population at large was "far from sympathetic to communism."[29][36] "Even if Jews were prominent in the Communist Party leadership, this prominence did not translate into support at the mass level" wrote Jeffrey Kopstein and Jason Wittenberg, who analyzed the communist vote in interwar Poland. Only 7% of Jewish voters supported communists at the polls in 1928, while 93% of them supported non-communists (with 49% voting for Piłsudski). The pro-Soviet communist party received most of its support from Belarusians whose separatism was backed by the Soviet Union. In Łwów, the CPP received 4% of the vote (of which 35% was Jewish), in Warsaw 14% (33% Jewish), and in Wilno 0.02% (36% Jewish). However, in terms of overall numbers, CPP was "the Jews' least favorite political grouping" during the 1928 elections.[5] It was the disproportionately large representation of Jews in the communist leadership that led to Żydokomuna sentiment being widely expressed in contemporary Polish politics.[37]

Invasion of Poland and the Soviet occupation zone

Following the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland, resulting in the partition of Polish territory between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (USSR), Jewish communities in eastern Poland welcomed with some relief the Soviet occupation, which they saw as a "lesser of two evils" than openly antisemitic Nazi Germany.[38][39][40] The image of Jews among the Belorussian and Ukrainian minorities waving red flags to welcome Soviet troops had great symbolic meaning in Polish memory of the period.[41] Young Jews joined or organized communist militias, others organized a new, communist, temporary self-government.[40] Such militias often disarmed and arrested Polish soldiers, policemen and other authority figures; often, Poles and the Polish states were mocked.[40] In the days and weeks following the events of September 1939, the Soviets engaged in a harsh policy of Sovietization. Polish schools and other institutions were closed, Poles were dismissed from jobs of authority, often arrested and deported, and replaced with non-Polish personnel.[42][43][44][45]According to some sources, the Poles resented their change of fortunes because, before the war, Poles had a privileged position. Then, in the space of a few days, Jews and other minorities from within Poland occupied positions in the Soviet occupation government—such as teachers, civil servants and engineers—that they allegedly had trouble achieving under the Polish government.[46][47] What to the majority of Poles was occupation and betrayal was, to some Jews—especially Polish communists of Jewish descent who emerged from the underground—an opportunity for revolution and retribution. There were even some extreme cases of Jewish participation in massacres of ethnic Poles such as Massacre of Brzostowica Mała.[47][48] Such behavior affronted non-Jewish Poles.

Such events implanted in the Polish collective memory the image of Jewish crowds greeting the invading Red Army as liberators, and willing collaborators,[40] further strengthening Żydokomuna sentiment that held Jews responsible for collaboration with the Soviet authorities in importing communism into divided Poland.[47][49][50] After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, widespread notion of Judeo-Communism, combined with the German Nazi encouragement for expression of antisemitic attitudes, may have been a principal cause of massacres of Jews by gentile Poles in Poland's northeastern Łomża province in the summer of 1941, including the massacre at Jedwabne according to Joanna B. Michlic.[51] However, the responsibility of the gentile Poles for the Jedwabne pogrom has been highly disputed, with some sources stating that the Germans were the principal authors of the massacre.

Though some Jews had initially benefited from the effects of the Soviet invasion, this occupation soon began to strike at the Jewish population as well; independent Jewish organizations were abolished and Jewish activists were arrested. Hundreds of thousands of Jews who had fled to the Soviet sector were given a choice of Soviet citizenship or returning to the German occupied zone. The majority chose the latter, and instead found themselves deported to the Soviet Union, where, ironically, 300,000 would escape the Holocaust.[47][52] While there was Polish Jewish representation in the London-based Polish government in exile, relations between the Jews in Poland and Polish resistance in occupied Poland were strained, and Jewish armed groups had difficulty joining the official Polish resistance umbrella organization, the Home Army (in Polish, Armia Krajowa or AK).[53][54] Some Jewish groups (such as the Bielski partisans) robbed local Polish peasants for food, also performing massacres and crimes like Naliboki massacre in 1943 ; in turn, the Polish underground often labeled those armed Jewish groups as "bandits" and "robbers."[55] Jewish partisans instead more often joined the Armia Ludowa of the communist Polish Workers' Party[55][56] and Soviet guerrilla groups, which increasingly clashed with Polish guerillas, contributing to yet another perception of Jews working with the Soviets against the Poles.[47]

Communist takeover of Poland in the aftermath of World War II

The Soviet-backed communist government was as harsh towards non-communist Jewish cultural, political and social institutions as they were towards Polish, banning all alternative parties.[57][58] Thousands of Jews returned from exile in the Soviet Union, but as their number decreased with legalized aliyah to Israel, the PZPR members formed a much larger percentage of the remaining Jewish population. Among them were a number of Jewish communists who played a highly visible role in the unpopular communist government and its security apparatus.[59]Hilary Minc, the third in command in Bolesław Bierut's political triumvirate of Stalinist leaders,[60] became the Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Industry, Industry and Commerce, and the Economic Affairs. He was personally assigned by Stalin first to Industry and than to Transportation ministries of Poland.[61] His wife, Julia, became the Editor-in-Chief of the monopolized Polish Press Agency. Minister Jakub Berman – Stalin's right hand in Poland until 1953 – held the Political propaganda and Ideology portfolios. He was responsible for the largest and most notorious secret police in the history of the People's Republic of Poland, the Ministry of Public Security (UB), employing 33,200 permanent security officers, one for every 800 Polish citizens.[60]

The new government's hostility to the wartime Polish Government in Exile and its World War II underground resistance – accused by the media of being nationalist, reactionary and antisemitic, and persecuted by Berman – further strengthened Żydokomuna sentiment to the point where in the popular consciousness Jewish Bolshevism was seen as having conquered Poland.[59] It was in this context, reinforced by the immediate post-war lawlessness, that Poland experienced an unprecedented wave of anti-Jewish violence (of which most notable was the Kielce pogrom).[62]

The Polish-American historian Marek Jan Chodakiewicz stressed that after the Soviet takeover of Poland in 1945 violence had developed amid postwar retribution and counter-retribution, exacerbated by the breakdown of law and order and a Polish anti-Communist insurgency.[63] According to Chodakiewicz, some Jewish "avengers" endeavored to extract justice from the Poles who harmed Jews during the War and in some cases Jews attempted to reclaim property confiscated by the Nazis. These phenomena further reinforced Żydokomuna sentiment. Chodakiewicz noted that after World War II, the Jews were not only victims, but also aggressors. He describes cases in which Jews cooperated with the Polish secret police, denouncing Poles and members of the Home Army. Chodakiewicz noted that some 3,500 to 6,500 Poles died in late 1940s because of Jewish denunciations or were killed by Jews themselves.[64] Encouraged by their Soviet advisors, many Jewish functionaries and government officials adopted new Polish-sounding names hoping to find less acrimony among their adversaries. "This practice often backfired and led to widespread speculation about 'hidden Jews' for decades to come."[65]

The combination of the effects of the Holocaust and postwar antisemitism led to a dramatic mass emigration of Polish Jewry in the immediate postwar years. Of the estimated 240,000 Jews in Poland in 1946 (of whom 136,000 were refugees from the Soviet Union, most on their way to the West), only 90,000 remained a year later.[66][67] The surviving Jews of Poland found themselves victims of the explosive postwar political situation. The image of the Jew as a threatening outsider took on a new form as antisemitism was now linked to the imposition of communist rule in Poland, including rumors of massive collaboration of Jews with the unpopular new regime and the Soviet Union. Of the fewer than 80,000 Jews who remained in Poland, many had political reasons for doing so. Consequently, – as noted by historian Michael C. Steinlauf – "their group profile ever more closely resembled the Żydokomuna."[68][69] Regarding this period, Andre Gerrits wrote in his study of Żydokomuna, that even though for the first time in history they had entered the top echelons of power in considerable numbers, "The first post-war decade was a mixed experience for the Jews of East Central Europe. The new communist order offered unprecedented opportunities as well as unforeseen dangers."[70]

Stalinist abuses

During Stalinism, the preferred Soviet policy was to keep sensitive posts in the hands of non-Poles. As a result, "all or nearly all of the directors (of the widely despised Ministry of Public Security of Poland) were Jewish" as noted by Polish journalist Teresa Torańska among others.[71][72] A recent study by the Polish Institute of National Remembrance showed that out of 450 people in director positions in the Ministry between 1944 and 1954, 167 (37.1%) were of Jewish ethnicity, while Jews made up only 1% of the post-war Polish population.[31] While Jews were overrepresented in various Polish communist organizations, including the security apparatus, relative to their percentage of the general population, the vast majority of Jews did not participate in the Stalinist apparatus, and indeed most were not supportive of communism.[47] Krzysztof Szwagrzyk has quoted Jan T. Gross, who argued that many Jews who worked for the communist party cut their ties with their culture – Jewish, Polish or Russian – and tried to represent the interests of international communism only, or at least that of the local communist government.[31]It is difficult to assess when the Polish Jews who had volunteered to serve or remain in the postwar communist security forces began to realize, however, what Soviet Jews had realized earlier, that under Stalin, as Arkady Vaksberg put it: "if someone named Rabinovich was in charge of a mass execution, he was perceived not simply as a Cheka boss but as a Jew..." [73]Among the notable Jewish officials of the Polish secret police and security services were Minister Jakub Berman, Joseph Stalin's right hand in the PRL; Vice-minister Roman Romkowski (head of MBP), Dir. Julia Brystiger (5th Dept.), Dir. Anatol Fejgin (10th Dept. or the notorious Special Bureau), deputy Dir. Józef Światło (10th Dept.), Col. Józef Różański among others. Światło – "a torture master" – defected to the West in 1953,[73] while Romkowski and Różański would find themselves among the Jewish scapegoats for Polish Stalinism in the political upheavals following Stalin's death, both sentenced to 15 years in prison on 11 November 1957 for gross violations of human rights law and abuse of power,but released 1964.[73][74][75]

In 1956, over 9,000 socialist and populist politicians were released from prison.[76] A few Jewish functionaries of the security forces were brought to court in the process of de-Stalinization. According to Heather Laskey, it was not a coincidence that the high ranking Stalinist security officers put on trial by Gomułka were Jews.[77] Władysław Gomułka was captured by Światło, imprisoned by Romkowski in 1951 and interrogated by both, him and Fejgin. Gomułka escaped physical torture only as a close associate of Joseph Stalin,[78] and was released three years later.[79] According to some sources, the categorization of the security forces as a Jewish institution—as disseminated in the post-war anticommunist press at various times—was rooted in Żydokomuna: the belief that the secret police was predominantly Jewish became one of the factors contributing to the post-war view of Jews as agents of the security forces.[80]

The Żydokomuna sentiment reappeared at times of severe political and socioeconomic crises in Stalinist Poland. After the death of Polish United Workers' Party leader Bolesław Bierut in 1956, a de-Stalinization and a subsequent battle among rival factions looked to lay blame for the excesses of the Stalin era. According to L.W. Gluchowski: "Poland’s communists had grown accustomed to placing the burden of their own failures to gain sufficient legitimacy among the Polish population during the entire communist period on the shoulders of Jews in the party."[73] (See: above.) As described in one historical account, the party hardline Natolin faction "used anti-Semitism as a political weapon and found an echo both in the party apparatus and in society at large, where traditional stereotypes of an insidious Jewish cobweb of political influence and economic gain resurfaced, but now in the context of 'Judeo-communism,' the Żydokomuna."[81] "Natolin" leader Zenon Nowak entered the concept of "Judeo-Stalinization" and placed the blame for the party's failures, errors and repression on "the Jewish apparatchiks." Documents from this period chronicle antisemitic attitudes within Polish society, including beatings of Jews, loss of employment, and persecution. These outbursts of antisemitic sentiment from both Polish society and within the rank and file of the ruling party spurred the exodus of some 40,000 Polish Jews between 1956 and 1958.[82][83]

1968 expulsions

Main article: 1968 Polish political crisis

Żydokomuna sentiment was reignited by Polish state propaganda as part of the 1968 Polish political crisis. Political turmoil of the late 1960s—exemplified in the West by increasingly violent protests against the Vietnam War—was closely associated in Poland with the events of the Prague spring which began on 5 January 1968, raising hopes of democratic reforms among the intelligentsia. The crisis culminated in the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia on 20 August 1968.[84][85] The repressive government of Władysław Gomułka

responded to student protests and strike actions across Poland (Warsaw,

Kraków) with mass arrests, and by launching an anti-Zionist campaign

within the communist party on the initiative of Interior Minister Mieczysław Moczar (aka Mikołaj Diomko, known for his xenophobic and antisemitic attitude).[86] The officials of Jewish descent were blamed "for a major part, if not all, of the crimes and horrors of the Stalinist period."[87]The campaign, which began in 1967, was a well-guided response to the Six-Day War and the subsequent break-off by the Soviets of all diplomatic relations with Israel. Polish factory workers were forced to publicly denounce Zionism. As the interior minister Mieczysław Moczar's nationalist "Partisan" faction became increasingly influential in the communist party, infighting within the Polish communist party led one faction to again make scapegoats of the remaining Polish Jews, attempting to redirect public anger at them. After Israel's victory in the war, the Polish government, following the Soviet lead, launched an antisemitic campaign under the guise of "anti-Zionism," with both Moczar's and Party Secretary Władysław Gomułka's factions playing leading roles. However, the campaign did not resonate with the general public, because most Poles saw similarities between Israel's fight for survival and Poland's past struggles for independence. Many Poles felt pride in the success of the Israeli military, which was dominated by Polish Jews. The slogan, "Our Jews beat the Soviet Arabs"[88] was very popular among the Poles, but contrary to the desire of the communist government.[89]