"Zarówno wypowiedzi Jarosława Kaczyńskiego, jak i Jarosława Rymkiewicza

sugerujące, że +Gazeta Wyborcza+ to spadkobiercy KPP, którzy propagują

ideologię luksemburgizmu, świadczą o tym, że mit żydokomuny jest w

Polsce ciągle żywy. Obaj w gruncie rzeczy przywołują ten termin, choć

nie wprost. To dowód na to, że mit żydokomuny nadal pojawia się w

różnych przebraniach, jest obecny w dyskursie publicznym, w grze

politycznej" - mówił Paweł Śpiewak, dyrektor Żydowskiego Instytutu

Historycznego, podczas środowej promocji swojej najnowszej książki

"Żydokomuna. Interpretacje historyczne".

Śpiewak podkreśla w swojej książce, że żydokomuna to nie realne

zjawisko, lecz ideologiczny mit, w którym zbiegły się wszystkie

antysemickie stereotypy z wielowiekowej tradycji oskarżania Żydów o

wszelkie dziejące się zło. Zdaniem Śpiewaka termin "żydokomuna" daje

możliwość głoszenia twierdzeń, że wszyscy Żydzi są nosicielami wrogiej

ideologii, czyli bolszewizmu.

"Zdaję sobie sprawę, że moja praca jest książką wysokiego ryzyka. Temat

żydokomuny jest wciąż gorący, wzbudza wielkie emocje. Wiem, że narażam

się antysemitom, ale do tego, że oni istnieją, już się przyzwyczaiłem" -

mówił Śpiewak dodając, że jego książka może też nie wzbudzić entuzjazmu

środowisk, które "psychologicznie, ideowo mają poczucie jakiegoś

związku z tamtym pokoleniem, żydowskich komunistów".

Śpiewak powiedział, że pracując nad "Żydokomuną" wzorował się na

sposobie pisania książek historycznych przez innego socjologa - Jana

Tomasza Grossa. "Nie ze wszystkimi stawianymi przez niego tezami się

zgadzam, ale odpowiada mi jego sposób prowadzenia narracji. To historia,

ale historia intelektualnie przetworzona, nie tylko suche fakty, ale

próba ich interpretacji, odczytania. Sposób pisania Grossa jest dla mnie

wzorcem" - powiedział Śpiewak.

W książce Śpiewak wielokrotnie podkreśla, że atrakcyjność ideologii

komunistycznej dla Żydów wynikała z ograniczeń, jakim podlegali. To

rewolucja po raz pierwszy w historii dała rosyjskim Żydom pełnię swobód

obywatelskich oraz możliwość pracy w administracji. Także w II

Rzeczpospolitej obowiązywało niepisane prawo ograniczające dostęp

ludności żydowskiej do stanowisk w administracji, wojsku, szkolnictwie,

na niektórych uczelniach obowiązywało getto ławkowe i numerus clausus.

Śpiewak zauważa, że w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym młodzi, aspirujący

do wyjścia z religijnego getta Żydzi nie mieli atrakcyjniejszej

propozycji niż proklamujące równość społeczną ruchy lewicowe.

Jak podaje Śpiewak, do Komunistycznej Partii Polski w 1933 roku

należało 8 tys. osób z czego 80 proc. stanowili Polacy, a około 20 proc.

Żydzi. Przedwojenny Związek Młodzieży Komunistycznej Polski, liczący w

połowie lat 30. niemal 12 tys. członków, w 42 proc. składał się z osób

pochodzenia żydowskiego. Sami komuniści zauważali, że Żydzi są w KPP

nadreprezentowani. W materiałach z 1929 roku znalazły się dane, że

"towarzysze żydowscy w miastach stanowią przeważnie ponad 50 proc.

składu organizacji, a są miasteczka, w których organizacja jest czysto

żydowska". Proporcje narodowościowe przechylały się na korzyść Żydów w

zarządzie partii. W styczniu 1936 roku na 30 członków Komitetu

Centralnego KPP było 15 Polaków, 12 Żydów, 2 Ukraińców i 1 Białorusin.

Wobec faktu, że Żydzi stanowili ok. 10 proc. przedwojennej ludności

Polski, można z tych liczb wyciągnąć wniosek o nadreprezantacji Żydów w

strukturach komunistycznych. Śpiewak jednak zwraca uwagę, że ogromna

większość polskich Żydów nie chciała mieć z komunizmem nic wspólnego. Na

KPP głosowało w 1928 roku 7 proc. społeczności żydowskiej, a 50 proc.

polskich Żydów oddało głosy na Bezpartyjny Blok Współpracy z Rządem,

czyli partię Piłsudskiego. Bardzo wielu Żydów głosowało też na partie

syjonistyczne.

W powojennej Polsce bardzo powszechne było przekonanie, że komunizm

wprowadzany jest przez Żydów, choć polska społeczność żydowska w

zasadzie przestała istnieć. Na czele państwa od 1945 roku stał

"triumwirat", jak to określa Śpiewak: Bolesław Bierut i dwie osoby

pochodzenia żydowskiego - Jakub Berman i Hilary Minc. W Komitecie

Centralnym PZPR w tym czasie udział Żydów wynosił 6 proc.

Śpiewak podaje, że w latach 1944-1945 na 450 osób pełniących najwyższe

funkcje w Ministerstwie Bezpieczeństwa Publicznego (od naczelnika

wydziału wzwyż) 167 (37 proc.) było pochodzenia żydowskiego. Im niżej w

strukturach UB, tym procent osób narodowości żydowskiej był niższy.

Śpiewak cytuje Ryszarda Terleckiego, który podaje, że w 1945 roku 95

proc. funkcjonariuszy UB było narodowości polskiej, a Żydów było ok. 2,5

proc. Jednak to Żydzi zasiadali na najbardziej widocznych stanowiskach.

"Po 20 latach niepodległości poza nielicznymi przypadkami nie

doczekaliśmy się żadnych poważnych opracowań na temat ruchu

komunistycznego w Polsce w jego różnych wymiarach. (...) Traktuję to, co

napisałem, jako pewien etap badań. Na pewno jest potrzeba ich

kontynuowania i mam nadzieję, że tak się stanie" - podsumował Śpiewak.

Książka "Żydokomuna. Interpretacje historyczne" ukazała się nakładem wydawnictwa Czerwone i Czarne. (PAP)

Antysemickie rysunki z polskiej prasy

okresu II RP, przedstawiające Żydów m.in. jako istoty demoniczne,

zaprezentuje wystawa „Obcy i niemili”, której wernisaż odbędzie się we

wtorek wieczorem w Żydowskim Instytucie Historycznym w Warszawie.

Otwarcie ekspozycji poprzedziła wtorkowa konferencja prasowa w ŻIH, z

udziałem twórców i organizatorów wystawy. Jak zgodnie podkreślili,

karykatury towarzyszące antysemickim artykułom z okresu międzywojennego

stanowiły istotny czynnik kształtowania odrażającego wizerunku Żyda,

wpływały na poglądy na temat mniejszości żydowskiej w II RP.

Dyrektor ŻIH prof. Paweł Śpiewak przypomniał, że w międzywojennej

Polsce nastąpił okres rozwoju żydowskiej kultury, szkolnictwa, tworzenia

przez Żydów partii politycznych; z drugiej jednak strony był to dla

wyznawców religii mojżeszowej czas dramatyczny. „Bojkot Żydów, getta

ławkowe i rysunki antysemickie w polskiej prasie tworzyły wokół Żydów

atmosferę nienawiści” – wyjaśnił Śpiewak.

Dyrektor ŻIH prof. Paweł Śpiewak przypomniał, że w międzywojennej

Polsce nastąpił okres rozwoju żydowskiej kultury, szkolnictwa, tworzenia

przez Żydów partii politycznych; z drugiej jednak strony był to dla

wyznawców religii mojżeszowej czas dramatyczny. „Bojkot Żydów, getta

ławkowe i rysunki antysemickie w polskiej prasie tworzyły wokół Żydów

atmosferę nienawiści” – wyjaśnił Śpiewak.

Jak dodał, przedstawianie w polskiej prasie Żydów jako zdeformowane

istoty przypominające zwierzęta, a nawet robactwo, sprzyjało powstawaniu

dystansu między Polakami i Żydami, który wywoływał obojętność w czasie

Holokaustu.

Wystawa składa się z trzech części. Pierwsza, zatytułowana „Oto Żyd”,

prezentuje rysunki ukazujące Żydów we wszystkich jego wcieleniach. „Od

przedstawień żydowskiego ciała, odbiegającego wyraźnie od normy

człowieczeństwa (...), poprzez ilustracje wyobrażenia o tzw. żydowskiej

mentalności, specyficznym żydowskim pomyślunku, aż po pokazanie Żydów

jako osoby z natury swej zmaterializowane” – wyjaśnił kurator ekspozycji

Dariusz Konstantynow.

Stereotypizacja Żydów w polskiej prasie lat 20. i 30. XX w. –

tłumaczył Konstantynow – zmierzała do przypisania im cech demonicznych.

„Żyd występuje tu jako diabeł wcielony” – zwrócił uwagę kurator.

Druga część wystawy, nazwana „Tam, gdzie mniejszość jest

większością”, poświęcona jest wyobrażeniom o roli mniejszości żydowskiej

w II RP. „Najogólniej mówiąc, Żyd we wszystkich tych rysunkach

występuje jako wróg (...). Jest wrogiem, kiedy jest komunistą i

bolszewikiem; jest wrogiem, gdy jest wyzyskiwaczem i kapitalistą” –

wyjaśnił Konstantynow. Zaznaczył, że żydowska mniejszość została ukazana

jako społeczność agresywna, dążąca do rozciągnięcia swych zgubnych

wpływów na całą Polskę.

Trzecia część ekspozycji – „Co zrobić z Żydami?” – przybliża obecne

na łamach antysemickiej prasy sposoby rozwiązania tzw. kwestii

żydowskiej. Na rysunkach przedstawiono rozmaite kierunki emigracji Żydów

z Polski; doceniono także nazistów, którzy podjęli „trud” rozprawienia

się z Żydami w swym kraju.

Zaprezentowane na wystawie prace były publikowane w okresie

międzywojennym na łamach m.in.: „Kuriera Poznańskiego”, „Dziennika

Bydgoskiego”, „ABC-Nowin Codziennych”, „Wieczoru Warszawskiego”,

„Podbipięty”, „Prosto z mostu”, „Szczutka”, „Szopki”, „Muchy”, „Żółtej

Muchy”, „Szarży”, „Pokrzyw” i „Szabes-Kuriera”.

Autorzy rysunków to zarówno znani artyści profesjonalni (m.in. Jerzy

Zaruba, Kamil Mackiewicz, Włodzimierz Bartoszewicz, Włodzimierz Łukasik,

Jerzy Srokowski, Kazimierz Grus i Maja Berezowska), jak i anonimowi,

podpisujący się monogramami i pseudonimami.

Oprócz obejrzenia antysemickich rysunków, zwiedzający wystawę będą

mogli zobaczyć film o mowie nienawiści, w którym głos zabrali m.in.

profesorowie: Jerzy Bralczyk i Michał Głowiński.

Organizatorem ekspozycji „+Obcy i niemili+. Antysemickie rysunki z

prasy polskiej 1919–1939” jest Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im.

Emanuela Ringelbluma w Warszawie.

Patronat medialny nad wystawą, która potrwa do końca stycznia 2014

r., sprawuje m.in. portal historyczny dzieje.pl, prowadzony przez Polską

Agencję Prasową i Muzeum Historii Polski. (PAP)

wmk/ abe/

http://dzieje.pl/wystawy/antysemickie-rysunki-w-polskiej-prasie-w-okresie-ii-rp-wystawa-w-zih

Żydokomuna

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Żydokomuna (

[ʐɨdɔkɔˈmuna], "

Judeo-Communism")

[1][2] is a

pejorative term for an

antisemitic canard[3] that refers to alleged

Jewish–

Soviet collaboration in importing

communism into

Poland,

[4] where communism was sometimes identified as part of a wider Jewish-led conspiracy to seize power.

[5] Historians dispute the claims of Żydokomuna.

The idea of Żydokomuna continued to endure to a certain extent in postwar Poland (1944–1956),

[6] because

Polish anti-communists

saw the Soviet-controlled Communist regime as the fruition of prewar

anti-Polish agitation; with it came the implication of Jewish

responsibility. The Soviet appointments of Jews to positions responsible

for oppressing the populace further fueled this perception.

[7][8] Some 37.1% of post-war management of

UB

employees and members of the communist authorities in Poland were of

Jewish origin. They were described in intelligence reports as very loyal

to the Soviets (Szwagrzyk).

[6]

Some Polish historians have impugned the loyalty of Jews returning to

Poland from the USSR after the Soviet takeover, which has raised the

specter of Żydokomuna in the minds of other scholars.

[9]

Prelude

According to some sources, the concept of a Jewish conspiracy threatening Polish social order dates in print to the pamphlet

Rok 3333 czyli sen niesłychany (The Year 3333, or the Incredible Dream) by

Polish Enlightenment author and political activist

Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz,

written in 1817 and published posthumously in 1858. Called "the first

Polish work to develop on a large scale the concept of an organized

Jewish conspiracy directly threatening the existing social structure,"

[10][11][12] it describes a

Warsaw of the future renamed Moszkopolis after its Jewish ruler.

[12] (See "

Judeopolonia" article for more.)

At the end of the 19th century,

Roman Dmowski's

National Democratic

party characterized Poland's Jews and other opponents of Dmowski's

party as internal enemies who were behind international conspiracies

inimical to Poland and who were agents of disorder, disruption and

socialism.

[13][14] Historian

Antony Polonsky

writes that before World War I "The National Democrats brought to

Poland a new and dangerous ideological fanaticism, dividing society into

'friends' and 'enemies' and resorting constantly to conspiratorial

theories ("Jewish-Masonic plot"; "

Żydokomuna"—"Jew-communism") to explain Poland's difficulties."

[15]

Meanwhile, Jews played into National Democratic rhetoric by affirming

themselves as alien through their participation in exclusively Jewish

organizations such as the

Bund and the

Zionist movement.

[13]

Origin

The term

Żydokomuna originated in connection with the Russian

Bolshevik Revolution and targeted Jewish communists during the

Polish-Soviet War. The emergence of the

Soviet state was seen by many Poles as Russian

imperialism in a new guise.

[12] The visibility of Jews in both the Soviet leadership and in the

Polish Communist Party further heightened such fears.

[12] In some circles,

Żydokomuna came to be seen as a prominent antisemitic stereotype

[16] expressing political paranoia.

[12]

Accusations of

Żydokomuna accompanied the incidents of anti-Jewish violence in Poland during

Polish–Soviet War

of 1920, legitimized as self-defense against a people who were

oppressors of the Polish nation. Some soldiers and officers in the

Polish eastern territories shared the conviction that Jews were enemies

of the Polish nation-state and were collaborators with Poland's enemies.

Some of these troops treated all Jews as Bolsheviks. According to some

sources, anticommunist sentiment was implicated in anti-Jewish violence

and killings in a number of towns, including the

Pinsk massacre, in which 35 Jews, taken as hostages, were murdered, and the

Lwów pogrom during the

Polish-Ukrainian War, in which 72 Jews were killed. Occasional instances of Jewish support for Bolshevism during the

Polish-Soviet War served to heighten anti-Jewish sentiment.

[17][18]

The concept of

Żydokomuna was widely illustrated in

Polish interwar politics, including publications by the

National Democrats[19] and the

Catholic Church that expressed anti-Jewish views.

[20][21][22] During

World War II, the term

Żydokomuna was made to resemble the

Jewish-Bolshevism rhetoric of

Nazi Germany, wartime

Romania[23] and other war-torn countries of

Central and

Eastern Europe.

[24]

Interbellum

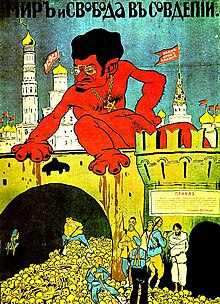

Polish anti-Bolshevik propaganda piece, 1920.

The National Democrats (

Endeks) emerged from the

1930 Polish elections to

Sejm as the main opposition party to the

Piłsudski government. Piłsudski had a liberal attitude towards minorities, and was respected by much of the Polish Jewish minority.

[25] In the midst of the

Great Depression and in a climate of widespread nationalist and antisemitic sentiment, the

Endeks expressed anti-Jewish sentiment to show their dissatisfaction with the government. The

Endeks

called for reducing the numbers of Jews in the country and for an

economic boycott (launched in 1931); subsequently, outbreaks of violence

occurred against Jews, particularly at universities. Following the

death of Piłsudski in 1935, the

Endeks moved towards seizing power in Poland, and began to focus more fully on the Jews. While there was a limited audience for

Endek

rhetoric, it was supplemented by the much larger circulation enjoyed by

Catholic Church publications, which increasingly referred to the

communist threat and the alleged "Godlessness" of the Jews. One such

Church publication, the newspaper

Samoobrona Narodu ("Self-Defense of the Nation," which meant defense against Jews), had a circulation of over one million.

[26]

In the period between the two world wars,

Żydokomuna sentiment grew concurrently in Poland with the notion of the "criminal Jew."

[27]

Statistics from the 1920s had indicated a Jewish crime rate that was

well below the percentage of Jews in the population. However, a

subsequent reclassification of how crime was recorded—which now included

minor offenses—succeeded in reversing the trend, and Jewish criminal

statistics showed an increase relative to the Jewish population by the

1930s. These statistics were seen by some Poles, particularly within the

right-wing press, to confirm the image of the "criminal Jew";

additionally, political crimes by Jews were more closely scrutinized,

enhancing fears of a criminal

Żydokomuna.

[27]

Another important factor was the dominance of Jews in the leadership of the

Communist Party of Poland (

KPP). According to multiple sources, Jews were well represented in the

Polish Communist Party.

[21][28] Notably, the party had strong Jewish representation at higher levels. Out of fifteen leaders of the

KPP central administration in 1936, eight were Jews. Jews constituted 53% of the "active members" of the

KPP,

75% of its "publication apparatus," 90% of the "international

department for help to revolutionaries" and 100% of the "technical

apparatus" of the Home Secretariat. In Polish court proceedings against

communists between 1927 and 1936, 90% of the accused were Jews. In terms

of membership, before its dissolution in 1938, 25% of

KPP members were Jews; most urban

KPP members were Jews—a substantial number, given an 8.7% Jewish minority in

prewar Poland.

[29] Some historians, including

Joseph Marcus,

qualify these statistics, alleging that the KPP should not be

considered a "Jewish party," as it was in fact in opposition to

traditional Jewish economic and national interests.

[30] The Jews supporting KPP saw themselves as international communists and rejected much of the Jewish culture and tradition.

[31] Nonetheless, the KPP, along with the

Polish Socialist Party, was notable for its decisive stand against antisemitism.

[32] According to Jaff Schatz's summary of Jewish participation in the prewar Polish communist movement:

Throughout the whole interwar period, Jews constituted a very

important segment of the Communist movement. According to Polish sources

and to Western estimates, the proportion of Jews in the KPP [the

Communist Party of Poland] was never lower than 22 percent. In the

larger cities, the percentage of Jews in the KPP often exceeded 50

percent and in smaller cities, frequently over 60 percent. Given this

background, a respondent's statement that "in small cities like ours,

almost all Communists were Jews," does not appear to be a gross

exaggeration.[33]

According to some bodies of research, voting patterns in Poland's

parliamentary elections in the 1920s revealed that Jewish support for

the communists was proportionally less than their representation in the

total population.

[34] In this view, most support for Poland's communist and pro-Soviet parties came not from Jews, but rather from Ukrainian and

Orthodox Belarusian voters,

[34]

though some of these may have been of Jewish ancestry. Schatz notes

that even if post-war claims by Jewish communists that 40% of the

266,528 communist votes on several lists of front organizations at the

1928 Sejm election came from the Jewish community were true (a claim that one source describes as "almost certainly an exaggeration"),

[35]

this would amount to no more than 5% of Jewish votes for the

communists, indicating the Jewish population at large was "far from

sympathetic to communism."

[29][36]

"Even if Jews were prominent in the Communist Party leadership, this

prominence did not translate into support at the mass level" wrote

Jeffrey Kopstein and Jason Wittenberg, who analyzed the communist vote

in interwar Poland. Only 7% of Jewish voters supported communists at the

polls in 1928, while 93% of them supported non-communists (with 49%

voting for Piłsudski). The pro-Soviet communist party received most of

its support from Belarusians whose separatism was backed by the Soviet

Union. In Łwów, the CPP received 4% of the vote (of which 35% was

Jewish), in Warsaw 14% (33% Jewish), and in

Wilno

0.02% (36% Jewish). However, in terms of overall numbers, CPP was "the

Jews' least favorite political grouping" during the 1928 elections.

[5] It was the disproportionately large representation of Jews in the communist leadership that led to

Żydokomuna sentiment being widely expressed in contemporary Polish politics.

[37]

Invasion of Poland and the Soviet occupation zone

Following the 1939

Soviet invasion of Poland, resulting in the

partition of Polish territory between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (USSR), Jewish communities in

eastern Poland welcomed with some relief the Soviet occupation, which they saw as a "lesser of two evils" than openly antisemitic

Nazi Germany.

[38][39][40] The image of Jews among the Belorussian and Ukrainian minorities waving red flags to welcome

Soviet troops had great symbolic meaning in Polish memory of the period.

[41] Young Jews joined or organized communist militias, others organized a new, communist, temporary self-government.

[40]

Such militias often disarmed and arrested Polish soldiers, policemen

and other authority figures; often, Poles and the Polish states were

mocked.

[40] In the days and weeks following the events of September 1939, the Soviets engaged in a harsh policy of

Sovietization.

Polish schools and other institutions were closed, Poles were dismissed

from jobs of authority, often arrested and deported, and replaced with

non-Polish personnel.

[42][43][44][45]

According to some sources, the Poles resented their change of

fortunes because, before the war, Poles had a privileged position. Then,

in the space of a few days, Jews and other minorities from within

Poland occupied positions in the Soviet occupation government—such as

teachers, civil servants and engineers—that they allegedly had trouble

achieving under the Polish government.

[46][47]

What to the majority of Poles was occupation and betrayal was, to some

Jews—especially Polish communists of Jewish descent who emerged from the

underground—an opportunity for revolution and retribution. There were

even some extreme cases of Jewish participation in massacres of ethnic

Poles such as

Massacre of Brzostowica Mała.

[47][48] Such behavior affronted non-Jewish Poles.

Such events implanted in the Polish collective memory the image of Jewish crowds greeting the invading

Red Army as liberators, and willing collaborators,

[40] further strengthening

Żydokomuna sentiment that held Jews responsible for collaboration with the Soviet authorities in importing communism into divided Poland.

[47][49][50] After the

German invasion of the Soviet Union

in 1941, widespread notion of Judeo-Communism, combined with the German

Nazi encouragement for expression of antisemitic attitudes, may have

been a principal cause of massacres of Jews by gentile Poles in Poland's

northeastern

Łomża province in the summer of 1941, including the massacre at

Jedwabne according to

Joanna B. Michlic.

[51]

However, the responsibility of the gentile Poles for the Jedwabne

pogrom has been highly disputed, with some sources stating that the

Germans were the principal authors of the massacre.

Though some Jews had initially benefited from the effects of the

Soviet invasion, this occupation soon began to strike at the Jewish

population as well; independent Jewish organizations were abolished and

Jewish activists were arrested. Hundreds of thousands of Jews who had

fled to the Soviet sector were given a choice of Soviet citizenship or

returning to the German occupied zone. The majority chose the latter,

and instead found themselves deported to the Soviet Union, where,

ironically, 300,000 would escape the

Holocaust.

[47][52] While there was Polish Jewish representation in the London-based

Polish government in exile, relations between the Jews in Poland and Polish resistance in

occupied Poland were strained, and Jewish armed groups had difficulty joining the official Polish resistance umbrella organization, the

Home Army (in

Polish, Armia Krajowa or AK).

[53][54] Some Jewish groups (such as the

Bielski partisans) robbed local Polish peasants for food, also performing massacres and crimes like

Naliboki massacre in 1943 ; in turn, the Polish underground often labeled those armed Jewish groups as "bandits" and "robbers."

[55] Jewish partisans instead more often joined the

Armia Ludowa of the communist

Polish Workers' Party[55][56] and

Soviet guerrilla groups, which

increasingly clashed with Polish guerillas, contributing to yet another perception of Jews working with the Soviets against the Poles.

[47]

Communist takeover of Poland in the aftermath of World War II

The

Soviet-backed communist government was as harsh towards non-communist

Jewish cultural, political and social institutions as they were towards

Polish, banning all alternative parties.

[57][58] Thousands of Jews returned from exile in the Soviet Union, but as their number decreased with legalized

aliyah

to Israel, the PZPR members formed a much larger percentage of the

remaining Jewish population. Among them were a number of Jewish

communists who played a highly visible role in the unpopular communist

government and its security apparatus.

[59]

Hilary Minc, the third in command in

Bolesław Bierut's political triumvirate of Stalinist leaders,

[60]

became the Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Industry, Industry and

Commerce, and the Economic Affairs. He was personally assigned by Stalin

first to Industry and than to Transportation ministries of Poland.

[61] His wife, Julia, became the Editor-in-Chief of the monopolized Polish Press Agency. Minister

Jakub Berman

– Stalin's right hand in Poland until 1953 – held the Political

propaganda and Ideology portfolios. He was responsible for the largest

and most notorious secret police in the history of the People's Republic

of Poland, the

Ministry of Public Security (UB), employing 33,200 permanent security officers, one for every 800 Polish citizens.

[60]

The new government's hostility to the wartime

Polish Government in Exile

and its World War II underground resistance – accused by the media of

being nationalist, reactionary and antisemitic, and persecuted by Berman

– further strengthened

Żydokomuna sentiment to the point where in the popular consciousness Jewish Bolshevism was seen as having conquered Poland.

[59] It was in this context, reinforced by the immediate post-war lawlessness, that Poland experienced an unprecedented wave of

anti-Jewish violence (of which most notable was the

Kielce pogrom).

[62]

The Polish-American historian

Marek Jan Chodakiewicz stressed that after the

Soviet takeover of Poland

in 1945 violence had developed amid postwar retribution and

counter-retribution, exacerbated by the breakdown of law and order and a

Polish anti-Communist insurgency.

[63]

According to Chodakiewicz, some Jewish "avengers" endeavored to extract

justice from the Poles who harmed Jews during the War and in some cases

Jews attempted to reclaim property confiscated by the Nazis. These

phenomena further reinforced

Żydokomuna sentiment. Chodakiewicz

noted that after World War II, the Jews were not only victims, but also

aggressors. He describes cases in which Jews cooperated with the Polish

secret police, denouncing Poles and members of the

Home Army.

Chodakiewicz noted that some 3,500 to 6,500 Poles died in late 1940s

because of Jewish denunciations or were killed by Jews themselves.

[64]

Encouraged by their Soviet advisors, many Jewish functionaries and

government officials adopted new Polish-sounding names hoping to find

less acrimony among their adversaries. "This practice often backfired

and led to widespread speculation about 'hidden Jews' for decades to

come."

[65]

The combination of the effects of the Holocaust and postwar

antisemitism led to a dramatic mass emigration of Polish Jewry in the

immediate postwar years. Of the estimated 240,000 Jews in Poland in 1946

(of whom 136,000 were refugees from the Soviet Union, most on their way

to the West), only 90,000 remained a year later.

[66][67]

The surviving Jews of Poland found themselves victims of the explosive

postwar political situation. The image of the Jew as a threatening

outsider took on a new form as antisemitism was now linked to the

imposition of communist rule in Poland, including rumors of massive

collaboration of Jews with the unpopular new regime and the Soviet

Union. Of the fewer than 80,000 Jews who remained in Poland, many had

political reasons for doing so. Consequently, – as noted by historian

Michael C. Steinlauf – "their group profile ever more closely resembled

the Żydokomuna."

[68][69] Regarding this period,

Andre Gerrits wrote in his study of

Żydokomuna,

that even though for the first time in history they had entered the top

echelons of power in considerable numbers, "The first post-war decade

was a mixed experience for the Jews of East Central Europe. The new

communist order offered unprecedented opportunities as well as

unforeseen dangers."

[70]

Stalinist abuses

During

Stalinism,

the preferred Soviet policy was to keep sensitive posts in the hands of

non-Poles. As a result, "all or nearly all of the directors (of the

widely despised

Ministry of Public Security of Poland) were Jewish" as noted by Polish journalist

Teresa Torańska among others.

[71][72] A recent study by the Polish

Institute of National Remembrance showed that out of 450 people in director positions in the

Ministry between 1944 and 1954, 167 (37.1%) were of Jewish ethnicity, while Jews made up only 1% of the post-war Polish population.

[31]

While Jews were overrepresented in various Polish communist

organizations, including the security apparatus, relative to their

percentage of the general population, the vast majority of Jews did not

participate in the Stalinist apparatus, and indeed most were not

supportive of communism.

[47] Krzysztof Szwagrzyk has quoted

Jan T. Gross,

who argued that many Jews who worked for the communist party cut their

ties with their culture – Jewish, Polish or Russian – and tried to

represent the interests of international communism only, or at least

that of the local communist government.

[31]

It is difficult to assess when the Polish Jews who had volunteered to

serve or remain in the postwar communist security forces began to

realize, however, what Soviet Jews had realized earlier, that under

Stalin, as Arkady Vaksberg put it: "if someone named Rabinovich was in

charge of a mass execution, he was perceived not simply as a Cheka boss

but as a Jew..." [73]

Among the notable Jewish officials of the Polish secret police and security services were Minister

Jakub Berman, Joseph Stalin's right hand in the

PRL; Vice-minister

Roman Romkowski (head of

MBP), Dir.

Julia Brystiger (5th Dept.), Dir.

Anatol Fejgin (10th Dept. or the notorious Special Bureau), deputy Dir.

Józef Światło (10th Dept.), Col.

Józef Różański among others. Światło – "a torture master" – defected to the West in 1953,

[73]

while Romkowski and Różański would find themselves among the Jewish

scapegoats for Polish Stalinism in the political upheavals following

Stalin's death, both sentenced to 15 years in prison on 11 November 1957

for gross violations of human rights law and abuse of power,but

released 1964.

[73][74][75]

In 1956, over 9,000 socialist and populist politicians were released from prison.

[76]

A few Jewish functionaries of the security forces were brought to court

in the process of de-Stalinization. According to Heather Laskey, it was

not a coincidence that the high ranking Stalinist security officers put

on trial by Gomułka were Jews.

[77] Władysław Gomułka was captured by

Światło, imprisoned by

Romkowski in 1951 and interrogated by both, him and

Fejgin. Gomułka escaped physical torture only as a close associate of

Joseph Stalin,

[78] and was released three years later.

[79]

According to some sources, the categorization of the security forces as

a Jewish institution—as disseminated in the post-war anticommunist

press at various times—was rooted in

Żydokomuna: the belief that

the secret police was predominantly Jewish became one of the factors

contributing to the post-war view of Jews as agents of the security

forces.

[80]

The

Żydokomuna sentiment reappeared at times of severe political and socioeconomic crises in Stalinist Poland. After the death of

Polish United Workers' Party leader

Bolesław Bierut in 1956, a

de-Stalinization

and a subsequent battle among rival factions looked to lay blame for

the excesses of the Stalin era. According to L.W. Gluchowski: "Poland’s

communists had grown accustomed to placing the burden of their own

failures to gain sufficient legitimacy among the Polish population

during the entire communist period on the shoulders of Jews in the

party."

[73] (See: above.) As described in one historical account, the party hardline

Natolin faction "used anti-Semitism as a political weapon and found an echo both in the party

apparatus

and in society at large, where traditional stereotypes of an insidious

Jewish cobweb of political influence and economic gain resurfaced, but

now in the context of 'Judeo-communism,' the Żydokomuna."

[81] "Natolin" leader

Zenon Nowak

entered the concept of "Judeo-Stalinization" and placed the blame for

the party's failures, errors and repression on "the Jewish

apparatchiks."

Documents from this period chronicle antisemitic attitudes within

Polish society, including beatings of Jews, loss of employment, and

persecution. These outbursts of antisemitic sentiment from both Polish

society and within the rank and file of the ruling party spurred the

exodus of some 40,000 Polish Jews between 1956 and 1958.

[82][83]

1968 expulsions

Żydokomuna sentiment was reignited by Polish state propaganda as part of the

1968 Polish political crisis. Political turmoil of the late 1960s—exemplified in the West by increasingly violent protests against the

Vietnam War—was closely associated in Poland with the events of the

Prague spring which began on 5 January 1968, raising hopes of democratic reforms among the intelligentsia. The crisis culminated in the

Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia on 20 August 1968.

[84][85] The repressive government of

Władysław Gomułka

responded to student protests and strike actions across Poland (Warsaw,

Kraków) with mass arrests, and by launching an anti-Zionist campaign

within the communist party on the initiative of Interior Minister

Mieczysław Moczar (aka Mikołaj Diomko, known for his xenophobic and antisemitic attitude).

[86] The officials of Jewish descent were blamed "for a major part, if not all, of the crimes and horrors of the Stalinist period."

[87]

The campaign, which began in 1967, was a well-guided response to the

Six-Day War and the subsequent break-off by the Soviets of all diplomatic relations with

Israel. Polish factory workers were forced to publicly denounce Zionism. As the interior minister

Mieczysław Moczar's

nationalist "Partisan" faction became increasingly influential in the

communist party, infighting within the Polish communist party led one

faction to again make scapegoats of the remaining Polish Jews,

attempting to redirect public anger at them. After Israel's victory in

the war, the Polish government, following the Soviet lead, launched an

antisemitic campaign under the guise of "anti-Zionism," with both

Moczar's and Party Secretary

Władysław Gomułka's

factions playing leading roles. However, the campaign did not resonate

with the general public, because most Poles saw similarities between

Israel's fight for survival and Poland's past struggles for

independence. Many Poles felt pride in the success of the Israeli

military, which was dominated by Polish Jews. The slogan, "Our Jews beat

the Soviet Arabs"

[88] was very popular among the Poles, but contrary to the desire of the communist government.

[89]

The government's antisemitic policy yielded more successes the next

year. In March 1968, a wave of unrest among students and intellectuals,

unrelated to the Arab-Israeli War, swept Poland (the events became known

as the

March 1968 events).

The campaign served multiple purposes, most notably the suppression of

protests, which were branded as inspired by a "fifth column" of

Zionists; it was also used as a tactic in a political struggle between

Gomułka and Moczar, both of whom played the Jewish card in a nationalist

appeal.

[87][90][91]

The campaign resulted in an actual expulsion from Poland in two years,

of thousands of Jewish professionals, party officials and state security

functionaries. Ironically, the Moczar's faction failed to topple

Gomułka with their propaganda efforts.

[92]

As historian Dariusz Stola notes, the anti-Jewish campaign combined

century-old conspiracy theories, recycled antisemitic claims and classic

communist propaganda. Regarding the tailoring of the

Żydokomuna sentiment to communist Poland, Stola suggested:

Paradoxically, probably the most powerful slogan of the communist

propaganda in March was the accusation that the Jews were zealous

communists. They were blamed for a major part, if not all, of the crimes

and horrors of the Stalinist period. The myth of Judeo-Bolshevism had

been well known in Poland since the Russian revolution and the

Polish-Bolshevik war of 1920, yet its 1968 model deserves interest as a

tool of communist propaganda. This accusation exploited and developed

the popular stereotype of Jewish communism to purify communism: the Jews

were the dark side of communism; what was wrong in communism was due to

them.[87]

The communist elites used the "Jews as Zionists" allegations to push

for a purge of Jews from scientific and cultural institutions,

publishing houses, and national television and radio stations.

[93]

Ultimately, the communist government sponsored an antisemitic campaign

that resulted in most remaining Jews being forced to leave Poland.

[94]

Moczar's "Partisan" faction promulgated an ideology that has been

described as an "eerie reincarnation" of the views of the pre-World War

II

National Democracy Party, and even at times exploiting

Żydokomuna sentiment.

[95]

Stola also notes that one of the effects of the 1968 antisemitic

campaign was to thoroughly discredit the communist government in the

eyes of the public. As a result, when the concept of the Jew as a

"threatening other" was employed in the 1970s and 1980s in Poland by the

communist government in its attacks on the political opposition,

including the

Solidarity trade-union movement and the

Workers' Defence Committee (

Komitet Obrony Robotników, or

KOR), it was completely unsuccessful.

[87]

Historiography

Historiography of Żydokomuna remains controversial.

[96] Works such as those by

Jan T. Gross

have polarized debate over anti-Jewish violence in Poland, with Gross

and his supporters characterizing Żydokomuna as an antisemitic cliché

while to some of his critics Żydokomuna was a fact of history.

[97] According to Gross's supporters, the strength of the

Żydokomuna

belief stemmed from age-old Polish fears of Russia and from

anti-communist and antisemitic attitudes. Schatz writes that "because

antisemitism was one of the main forces that drew Jews to the Communist

movement, Żydokomuna meant turning the effects of antisemitism into a

cause of its further increase."

[98][99] Żydokomuna boosted antisemitism by amplifying ideas about an alleged "

Jewish world conspiracy."

[2]

According to this thinking, Bolshevism and communism became "the modern

means to the long-attempted Jewish political conquest of Poland; the

Żydokomuna conspirators would finally succeed in establishing a '

Judeo-Polonia.'"

[100] Subscribers to this theory maintain that there was a strong tradition of antisemitism which provided a base for

Żydokomuna to feed upon.

[2][10][11][12][101]

These sources claim that many Poles likely exaggerated Jewish

participation in the Soviet occupation because a Jewish presence in the

government apparatus was a novel phenomenon in pre-war Poland.

[4] Critics of these sources, such as

Niall Ferguson,

claim that much of the anti-Jewish sentiment was justified due to the

disproportionate influence of Jewish communists in carrying out Soviet

policies. According to Ferguson, "The entire Polish population adopted a

negative attitude towards the Jews because of their blatant cooperation

with the Bolsheviks and their hostility against non-Jews."

[102]

Historian

Omer Bartov

has written that "recent writings and pronouncements seem to indicate

that the myth of the Żydokomuna (Jews as communists) has not gone away"

as evidenced by the writings of younger Polish scholars such as

Marek Chodakiewicz, contending Jewish disloyalty to Poland during the

Soviet occupation.

[9] Historians

Joanna B. Michlic and

Laurence Weinbaum charge that post-1989 Polish historiography has seen a revival of "an ethnonationalist historical approach".

[97][103]

According to Michlic, among some Polish historians, "[myth of

żydokomuna] served the purpose of rationalizing and explaining the

participation of ethnic Poles in killing their Jewish neighbors and,

thus, in minimizing the criminal nature of the murder."

[97][104]

See also

- History of the Jews in Poland

- History of the Jews in Russia: Jews in the revolutionary movement

Jewish Bolshevism

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Judeo-Communism)

For the participation of the Jews in the Russian revolutionary movement, see

Bundism.

In Poland, "Judeo-Bolshevism" was and is known as "Żydokomuna" .[2]

The expression was the title of a pamphlet, The Jewish Bolshevism, and became current after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, featuring prominently in the propaganda of the anti-communist "White" forces during the Russian Civil War.

The theory was propagated by the Nazi Party and their American sympathizers.[3][4][5][6]

Origins

The conflation of Jews and revolution emerged in the atmosphere of destruction of Russia during World War I. When the revolutions of 1917

crippled Russia's war effort, conspiracy theories grew up - even far

from Berlin and Petrograd, many Britons for example, ascribed the

Russian Revolution to an "apparent conjunction of Bolsheviks, Germans

and Jews."[8]

The worldwide spread of the concept in the 1920s is associated with the publication and circulation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,

a fraudulent document that purported to describe a secret Jewish

conspiracy aimed at world domination. The expression made an issue out

of the Jewishness of some leading Bolsheviks (most notably Leon Trotsky) during and after the October Revolution. Daniel Pipes says that "primarily through the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the Whites spread these charges to an international audience." James Webb wrote that it is rare to find an antisemitic source after 1917 that ..."does not stand in debt to the White Russian analysis of the Revolution."

Jewish involvement in Russian Communism

Antisemitism in the Russian Empire was both on cultural level and institutionalized. The Jews were restricted to live within the Pale of Settlement,[11] as well as subjected to sporadic pogroms.[12][13] In the period from 1881 to 1920, more than two million Jews left Russia.[14]

Conditions in Russia (1924) A Census - Bolsheviks by Ethnicity

As a result, Jews in relatively large numbers joined various

ideological currents favoring gradual or revolutionary changes within

the Russian Empire. Those movements ranged from the far left (anarchists,[15] Bundists, Bolsheviks, Mensheviks) to moderate left (Trudoviks) and constitutionalist (Constitutional Democrats) parties.On the eve of the February Revolution in 1917, of about 23,000 members of the Bolshevik party 364 (about 1.6%) were known to be ethnic Jews.[14]

According to the 1922 Bolshevik party census, there were 19,564 Jewish

Bolsheviks, comprising 5.21% of the total, and in the 1920s of the 417

members of the Central Executive Committee, the party Central Committee,

the Presidium of the Executive of the Soviets of the USSR and the

Russian Republic, the People's Commissars, 6% were ethnic Jews. Between 1936 and 1940, during the Great Purge, Yezhovshchina and after the rapprochement with Nazi Germany, Stalin had largely eliminated Jews from senior party, government, diplomatic, security and military positions.

An example of the exaggeration of Jewish influence in the Soviet Communist Party is the estimate by Alfred Jensen that in the 1920s "75 per cent of the leading Bolsheviks" were "of Jewish origin" quoted by journalist David Aaronovitch.[better source needed]

According to Aaronovitch, "a cursory examination of membership of the

top committees shows this figure to be an absurd exaggeration".[21]

Nazi Germany

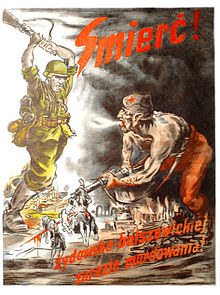

Anti-Soviet Nazi propaganda poster in the Polish language, the text reads "Death! to Jewish-Bolshevik pestilence of murdering!"

Walter Laqueur traces the Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy theory to Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, for whom Bolshevism was "the revolt of the Jewish, Slavic and Mongolian races against the German (Aryan)

element in Russia". Germans, according to Rosenberg, had been

responsible for Russia's historic achievements and had been sidelined by

the Bolsheviks, who did not represent the interests of the Russian

people, but instead those of its ethnic Jewish and Chinese population.

Michael Kellogg in his Ph.D. thesis argues that the racist ideology of Nazis was to a significant extent influenced by White emigres

in Germany, many of whom while being former subjects of the Russian

Empire, were of non-Russian descent: ethnic Germans, residents of Baltic

lands, including Baltic Germans, and Ukrainians. Of particular role was

their Aufbau organization (Aufbau: Wirtschafts-politische

Vereinigung für den Osten (Reconstruction: Economic-Political

Organization for the East). For example, its leader was instrumental in

making the Protocols of The Elders of Zion available in German

language. He argues that early Hitler was rather philosemitic, and

became rabidly anti-Semitic since 1919 under the influence of the White

emigre convictions about the conspiracy of the Jews, an unseen unity

from financial capitalists to Bolsheviks, to conquer the world.[23]

Therefore, his conclusion is that White emigrees were at the source of

the Nazist concept of Jewish Bolshevism. Annemarie Sammartino argues

that this view is contestable. While there is no doubt that White

emigres were instrumental in reinforcing the idea of 'Jewish Boslhevism'

among Nazis, the concept is also found in many German early

post-World-War-I documents. Also, Germany had its own share of Jewish

Communists "to provide fodder for the paranoid fantasies of German

antisemites" without Russian Bolsheviks.[24]

During the 1920s, Hitler declared that the mission of the Nazi movement was to destroy "Jewish Bolshevism". Hitler asserted that the "three vices" of "Jewish Marxism" were democracy, pacifism and internationalism, and that the Jews were behind Bolshevism, communism and Marxism.

In Nazi Germany,

this concept of Jewish Bolshevism reflected a common perception that

Communism was a Jewish-inspired and Jewish-led movement seeking world

domination from its origin. The term was popularized in print in German

journalist Dietrich Eckhart's 1924 pamphlet "Der Bolschewismus von Moses bis Lenin" ("Bolshevism from Moses to Lenin") which depicted Moses and Lenin as both being Communists and Jews. This was followed by Alfred Rosenberg's 1923 edition of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Hitler's Mein Kampf in 1925, which saw Bolshevism as "Jewry's twentieth century effort to take world dominion unto itself."

According to French spymaster and writer Henri Rollin,

"Hitlerism" was based on "anti-Soviet counter-revolution" promoting the

"myth of a mysterious Jewish-Masonic-Bolshevik plot", entailing that

the First World War

had been instigated by a vast Jewish-Masonic conspiracy to topple the

Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian Empires and implement Bolshevism

by fomenting liberal ideas.[page needed]

A major source for propaganda about Jewish Bolshevism in the 1930s and early 1940s was the pro-Nazi and antisemitic international Welt-Dienst news agency founded in 1933 by Ulrich Fleischhauer.

Within the German Army, a tendency to see Soviet Communism as a

Jewish conspiracy had grown since the First World War, something that

became officialised under the Nazis. A 1932 pamphlet by Ewald Banse

of the Government-financed German National Association for the Military

Sciences described the Soviet leadership as mostly Jewish, dominating

an apathetic and mindless Russian population.

Propaganda produced in 1935 by the psychological war laboratory of

the German War Ministry described Soviet officials as "mostly filthy

Jews" and called on Red Army

soldiers to rise up and kill their "Jewish commissars". This material

was not used at the time, but served as a basis for propaganda in the

1940s.

Members of the SS were encouraged to fight against the "Jewish Bolshevik sub-humans". In the pamphlet The SS as an Anti-Bolshevist Fighting Organization, published in 1936, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler wrote:

We shall take care that never again in Germany, the heart of Europe,

will the Jewish-Bolshevistic revolution of subhumans be able to be

kindled either from within or through emissaries from without.

In his speech to the Reichstag justifying Operation Barbarossa in 1941, Hitler said:

For more than two decades the Jewish Bolshevik regime in Moscow had

tried to set fire not merely to Germany but to all of Europe…The Jewish

Bolshevik rulers in Moscow have unswervingly undertaken to force their

domination upon us and the other European nations and that is not merely

spiritually, but also in terms of military power…Now the time has come

to confront the plot of the Anglo-Saxon Jewish war-mongers and the

equally Jewish rulers of the Bolshevik centre in Moscow!

Field-Marshal Wilhelm Keitel

gave an order on 12 September 1941 which declared: "the struggle

against Bolshevism demands ruthless and energetic, rigorous action above

all against the Jews, the main carriers of Bolshevism.

Historian Richard J. Evans

wrote that Wehrmacht officers regarded the Russians as "sub-human", and

were from the time of the invasion of Poland in 1939 telling their

troops the war was caused by "Jewish vermin", explaining to the troops

that the war against the Soviet Union was a war to wipe out what were

variously described as "Jewish Bolshevik subhumans", the "Mongol

hordes", the "Asiatic flood" and the "red beast", language clearly

intended to produce war crimes by reducing the enemy to something less

than human.

Joseph Goebbels published an article in 1942 called "the so-called Russian soul" in which he claimed that Bolshevism was exploiting the Slavs and that the battle of the Soviet Union determined whether Europe would become under complete control by international Jewry.[35]

Nazi propaganda presented Barbarossa as an ideological-racial war

between German National Socialism and "Judeo-Bolshevism", dehumanising

the Soviet enemy as a force of Slavic Untermensch

(sub-humans) and "Asiatic" savages engaging in "barbaric Asiatic

fighting methods" commanded by evil Jewish commissars whom German troops

were to grant no mercy.

The vast majority of the Wehrmacht officers and soldiers tended to

regard the war in Nazi terms, seeing their Soviet opponents as

sub-human.

While National Socialism

brought about a new version and formulation of European culture,

Bolshevism is the declaration of war by Jewish-led international

subhumans against culture itself. It is not only anti-bourgeois, it is

anti-cultural. It means, in the final consequence, the absolute

destruction of all economic, social, state, cultural, and civilizing

advances made by western civilization for the benefit of a rootless and

nomadic international clique of conspirators, who have found their

representation in Jewry.

— Joseph Goebbels, Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg, September 1935[38]

Outside Nazi Germany

Great Britain, 1920s

In the early 1920s, a leading British antisemite, Henry Hamilton Beamish, stated that Bolshevism was the same thing as Judaism. In the same decade, future wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill penned an editorial entitled "Zionism versus Bolshevism," which was published in the Illustrated Sunday Herald. In the article, which asserted that Zionism

and Bolshevism were engaged in a "struggle for the soul of the Jewish

people", he called on Jews to repudiate "the Bolshevik conspiracy" and

make clear that "the Bolshevik movement is not a Jewish movement" but

stated that:

[Bolshevism] among the Jews is nothing new. From the days of Spartacus-Weishaupt to those of Karl Marx, and down to Trotsky (Russia), Bela Kun (Hungary), Rosa Luxemburg (Germany), and Emma Goldman

(United States), this world-wide conspiracy for the overthrow of

civilisation and for the reconstitution of society on the basis of

arrested development, of envious malevolence, and impossible equality,

has been steadily growing.

Author Gisela C. Lebzelter

noted that Churchill's analysis failed to analyze the role that Russian

oppression of Jews had played in their joining various revolutionary

movements, but instead "to inherent inclinations rooted in Jewish

character and religion."

Works propagating the Jewish Bolshevism canard

The Jewish Bolshevism

The Jewish Bolshevism is a 31- or 32-page antisemitic pamphlet published in London in 1922 and 1923 by the Britons Publishing Society. It included a foreword by the German Nazi leader Alfred Rosenberg who promulgated the concept of "Jewish Bolshevism".

This relatively obscure publication embodies the Nazi doctrine that "Jewishness" and Bolshevism

are the same; or that Bolshevism is Jewish, whether everything Jewish

is included within Bolshevism. The methodology used consists of

identifying Bolsheviks as Jews; by birth, or by name or by demographics.

According to Singerman, The Jewish Bolshevism, which he dubs as item "0121" in his Bibliography, is "Identical in content to item "0120", the pamphlet The Grave Diggers of Russia, which was published in 1921 in Germany, by Dr. E. Boepple. In 1922, historian Gisela C. Lebzelter

wrote: "The Britons published a brochure entitled Jewish Bolshevism,

which featured drawings of Russian leaders supplemented by brief

comments on their Jewish descent and affiliation. This booklet, which

was prefaced by Alfred Rosenberg, had previously been published in English by völkisch Deutscher Volksverlag."[42]

The Octopus

The Octopus is a 256-page book self-published in 1940 by Elizabeth Dilling under the pseudonym "Rev. Frank Woodruff Johnson".[43]

Behind Communism

Frank L. Britton, editor of The American Nationalist published a book, Behind Communism, in 1952 which disseminated the myth that Communism was a Jewish conspiracy originating in Palestine.

Dismissal of the concept

Researchers in the topic, such as Polish philosopher Stanisław Krajewski "[45] or André Gerrits, denounce the concept of "Jewish Bolshevism" as a prejudice. Law professor Ilya Somin

agrees, and compares Jewish involvement in other communist countries.

"Overrepresentation of a group in a political movement does not prove

either that the movement was "dominated" by that group or that it

primarily serves that group’s interests. The idea that communist

oppression was somehow Jewish in nature is belied by the record of

communist regimes in countries like China, North Korea, and Cambodia, where the Jewish presence was and is minuscule."[47]

See also

- Cultural Bolshevism

- Cultural Marxism

-