Emergency apps don't provide 'what people really want' in a disaster, U of C researchers say

Team hopes software that analyzes social media posts will help tailor official apps to actual needs

By Robson Fletcher, CBC News

Posted: Jun 19, 2017 3:39 PM MT

Last Updated: Jun 19, 2017 3:39 PM MT

Maleknaz Nayebi, a PhD candidate at the University of

Calgary's Schulich School of Engineering, was the lead researcher in a

project that used specialized software to analyze nearly 70,000 tweets

sent by affected residents during the Fort McMurray wildfire of 2016.

(Left: Mark Blinch/Reuters, Right: Justin Pennell/CBC)

The team used specialized software to analyze nearly 70,000 tweets sent by affected residents during the catastrophe to gauge "what people really want," said lead researcher Maleknaz Nayebi, a PhD candidate at the Schulich School of Engineering.

"The results were pretty surprising — and not really good," she said.

The team counted 144 different features people wanted to get out of their smartphones in the emergency situation and ranked them in terms of priority.

They then compared the list to what's currently available from the Alberta government's wildfire app and 25 other, similar apps available throughout North America and Australia.

"We found that among the top 10 essential (desired) features, none of them are provided right in any of these 26 apps," Nayebi said.

Overall, she said about 80 per cent of the features people are looking for aren't actually available at the moment.

Challenges in software design

The conclusions are not an indictment of the current app providers, she said, noting it's actually quite tricky to design software, from the get-go, in a way targeted users will actually use."But when we bring software into society that we want to help people in crisis or emergency events, we need to be more careful and really consider what they want," Nayebi said.

"We cannot speculate on what people want. We really need to rely on evidence."

Guenther Ruhe is a professor of computer

engineering at the Schulich School of Engineering at the University of

Calgary. (Justin Pennell/CBC)

"This is a lightweight method with good results and we would be very happy to help … organizations to use it," Nayebi said.

Her PhD supervisor, Guenther Ruhe, said that's part of the mandate for researchers at the Schulich School.

"I think … we have a huge responsibility as researchers, not only writing papers and getting citations, but having impact," he said.

"We want to do things we can demonstrate are useful in real life."

According to the team's research, the 10 most desired features in an emergency app are:

- Fire alarm notification.

- Food and water requests and resource.

- Emergency maintenance service.

- Send emergency text messages.

- Safety guidelines.

- Fire and safeness warning.

- Request ambulance at a tap.

- Find nearest gas station.

- Emergency zones maps.

- Find a medical centre.

In Case of Emergency

„ICE“ (kurz für „In Case of Emergency“, engl. ‚im Notfall‘) bezeichnet ein umstrittenes Verfahren zur Kennzeichnung von Adressbucheinträgen in Mobiltelefonen. Die Rufnummern von Angehörigen, die in einem Notfall benachrichtigt werden sollen, werden unter dem Kürzel „ICE“ abgespeichert. Im deutschsprachigen Raum wird alternativ auch das Kürzel „IN“ („Im Notfall“) verwendet.Logo von Im Notfall

Anfang 2005 hat der britische Rettungssanitäter Bob Brotchie eine Initiative zur Verbreitung dieses Verfahrens begonnen. Das Verfahren soll Rettungsdiensten erleichtern, die Angehörigen von Unfallopfern zu ermitteln.[1] Später hat Bob Brotchie in Großbritannien die Bezeichnung „ICE“ als Marke schützen lassen und einen kostenpflichtigen Dienst zur telefonischen Benachrichtigung Angehöriger unter dieser Bezeichnung gegründet.

Durch Medienberichte[2] und Kettenbriefe[3] hat das Verfahren in einigen Ländern Bekanntheit erlangt. Im Juli 2005 tauchte erstmals in einem Blog die Idee auf, im deutschsprachigen Raum statt „ICE“ das leichter verständliche „IN“ zu verwenden.[4] Seit 2008 empfiehlt die internationale Norm E.123 ein sprachunabhängiges Verfahren, das Ziffern und aussagekräftige Namen zur Kennzeichnung wichtiger Nummern verwendet.

Anleitung

Anleitung für das Kennzeichnen von Kontaktpersonen für Notfälle im Adressbuch von Mobiltelefonen nach dem „IN“-Verfahren:

- Im Handy einen Kontakt namens „IN“ anlegen, gefolgt vom Namen der Kontaktperson, z. B. „IN Mutter“ oder „IN David“.

- Die Telefonnummer der Kontaktperson speichern.

- Die IN-Kontaktperson(in) davon in Kenntnis setzen, dass man sie als solche im Handy führt.

Kettenbriefe

Im Zusammenhang mit dem ICE-Verfahren sind mindestens zwei E-Mail-Kettenbriefe im Umlauf. Der eine wirbt für die Verwendung des ICE-Verfahrens unter Berufung auf vermeintliche Empfehlungen angesehener Organisationen.[3] Der andere ist eine Falschmeldung, die vor einem vermeintlichen Handy-Virus warnt.[5] Beide E-Mails enthalten mutwillig gefälschte und irreführende Angaben und sollten nicht weiterverteilt, sondern sofort gelöscht werden.Kritik und Positionen von Rettungsdiensten

Deutschland

- Der Arbeiter-Samariter-Bund Deutschland (ASB) hielt in einer Pressemeldung im Jahr 2009 ausdrücklich fest, dass Empfehlungen für ICE-Nummern nicht von offizieller Seite verschickt werden und bat darum, diese nicht zu beachten und nicht weiterzuleiten. Weiters riet der ASB von dem ICE-Verfahren ab, da nicht ausgeschlossen werden könnte, dass die ICE-Nummern von Dritten missbräuchlich verwendet werden könnten. Stattdessen empfahl der ASB, im Geldbeutel eine Notiz mit den Daten der im Notfall zu informierenden Personen zu hinterlegen[6].

- In einem Artikel der Norddeutschen Neuesten Nachrichten aus dem Jahr 2014 stand René Glaeser, der Werkleiter Rettungsdienst beim Landkreis Prignitz, dem ICE-System skeptisch gegenüber. Einerseits, weil in erster Linie die Behandlung der Notfallpatienten und nicht die Benachrichtigung von Angehörigen im Vordergrund stehe und andererseits aus Sicht des Datenschutzes, da der Zugriff auf Daten von Angehörigen durch Dritte nicht ausreichend geschützt sei.[7]

- Lutz Dieckmann vom Notärzteverein Prignitz und zugleich ärztlicher Leiter des Rettungsdienstes beim Landkreis Prignitz betrachtete die Kennzeichnung wichtiger Telefonkontakte grundsätzlich als sinnvoll. Dieckmann merkte jedoch ebenfalls an, dass der Datenschutz zu klären sei und empfahl, Informationen zur Benachrichtigung von Angehörigen schriftlich zusammen mit dem Personalausweis zu verwahren.[7]

Österreich

Das Österreichische Rote Kreuz (ÖRK) unterstützt ICE-Nummern grundsätzlich, empfiehlt jedoch anstatt „ICE“ die Verwendung des Kürzels „IN“. Einerseits wegen der möglichen Verwechslung mit Bob Brotchies kostenpflichtigem Telefondienst, da nach Ansicht des ÖRK die Initiative „frei von finanziellen Interessen bleiben“ sollte. Außerdem wird die Verwendung der Bezeichnung „IN“ empfohlen, um Mißverständnisse zu vermeiden, da das Kürzel ICE im deutschsprachigen Raum bereits mit dem Hochgeschwindigkeitszug Intercity-Express assoziiert werde.[8]Schweiz

Der schweizerische Interverband für Rettungswesen (IVR) distanziert sich ebenfalls von den Kettenbriefen und dem ICE/IN-Verfahren und stellt fest, dass damit aus verschiedenen Gründen „kaum ein verwertbarer Nutzen“ erzielt werden könne. Laut IVR sei es eine „schlichtweg falsche Behauptung“, dass es sich bei der Verbreitung des ICE-Verfahrens um ein „Anliegen der Rettungsdienste“ handle, wie in der Betreffzeile des Kettenbriefes behauptet werde, weiters bezeichnet der IVR die Verbreitung in Form eines Kettenbriefes als „nicht nur fragwürdig, sondern geradezu verwerflich“. Unter anderem kritisiert der IVR, dass Helfer dazu verleitet werden könnten, im Mobiltelefon nach einem solchen Eintrag zu suchen, anstatt Lebensrettende Sofortmassnahmen durchzuführen und Erste Hilfe zu leisten.[9]In Case of Emergency

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In case of emergency (ICE) is a program that enables first responders, such as paramedics, firefighters, and police officers, as well as hospital personnel, to contact the next of kin of the owner of a mobile phone

to obtain important medical or support information (the phone must be

unlocked and working). The phone entry (or entries) should supplement or

complement written (such as wallet, bracelet, or necklace) information or indicators. The programme was conceived in the mid-2000s and promoted by British paramedic Bob Brotchie in May 2005.[1] It encourages people to enter emergency contacts in their mobile phone address book

under the name "ICE". Alternatively, a person can list multiple

emergency contacts as "ICE1", "ICE2", etc. The popularity of the program

has spread across Europe and Australia, and it has started to grow into North America.[2]

Overview

Following research carried out by Vodafone that showed that fewer than 25% of people carry any details of who they would like telephoned following a serious accident, a campaign encouraging people to do this was started in May 2005 by Bob Brotchie of the East Anglia Ambulance Service in the UK. The idea has taken off since 7 July 2005 London bombings.[3]When interviewed on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme on 12 July 2005, Brotchie said:

"I was reflecting on some difficult calls I've attended, where people were unable to speak to me through injury or illness and we were unable to find out who they were. I discovered that many people, obviously, carry mobile phones and we were using them to discover who they were. It occurred to me that if we had a uniform approach to searching inside a mobile phone for an emergency contact then that would make it easier for everyone."Brotchie also urged mobile phone manufacturers to support the campaign by adding an ICE heading to phone number lists of all new mobile phones.

With this additional information and medical information, first responders can access this information from the victim's phone in the event of an emergency. In the event of a major trauma, it is critical to have this information within the golden hour, which can increase the chances of survival.

In Germany, the In Case of Emergency concept has been criticised for some reasons:[4]

- Medical service personnel on site normally do not have the time to contact relatives. Information stored in a phone is thus useless for medical care prior to hospital.

- Contacting relatives of a seriously injured person is a sensitive task that is not carried out by telephone in the first place.

Many smartphone models have dedicated ICE contact information functionality either built into the OS or available as apps. Saving duplicate phone numbers on a phone without dedicated ICE functionality may cause the ICE and regular contacts to be combined, or cause the caller ID to fail for incoming calls from a close friend or relative. (To avoid this, some use the "tel:" URI scheme to put the phone number in the ICE contact's "home page" field.)

Locked phones

For security purposes, many mobile phone owners now lock their mobiles, requiring a passcode to be entered in order to access the device. This hinders the ability of first responders to access the ICE phone list entry. In response to this problem, many device manufacturers have provided a mechanism to specify some text to be displayed while the mobile is in the locked state. The owner of the phone can specify their "In Case of Emergency" contact and also a "Lost and Found" contact. For example, BlackBerry mobiles permit the "Owner" information to be set in the Settings → Options → Owner menu item.Alternatively, some handsets provide access to a list of ICE contacts directly from the "locked" screen. There are also smartphone "apps" (applications) that allow custom ICE and emergency information to be displayed as the "locked" screen. For instance, the Medical ID android app enables quick access to medical information and emergency contacts.

In case of emergency

Karta ICE

- w książce adresowej telefonu komórkowego – jako kontakt „ICE” wpisuje się numer telefonu wybranej osoby. Jeśli takich osób jest kilka, to oznacza się je hasłami „ICE1”, „ICE2” itd.

- na karcie „ICE” wielkości wizytówki wpisuje się imię, nazwisko i numer kontaktowy najbliższych osób. Kartę powinno się nosić cały czas przy sobie.

Zobacz też

112 (numer alarmowy)7 essential personal safety apps for emergency situations

Just hours after coordinated attacks in Paris left at least 127 people dead and injured more than 350, Facebook activated its Safety Check tool. The tool, which automatically sends users in the affected area a prompt asking if they’re safe, notifies Facebook friends when a user clicks “Yes, let my friends know.”

Since its official launch in October 2014, Safety Check has been activated only a handful of times, including after the recent earthquakes in Afghanistan, Chile and Nepal. More than 4 million people used the tool to mark themselves safe following the Paris attacks. This was the first time the program was used outside of a natural disaster.

Alex Schultz, Facebook’s vice president of growth, notes that “communication is critical in moments of crisis.” As social media grows in popularity as a go-to resource for help, what other tools are there for emergency response?

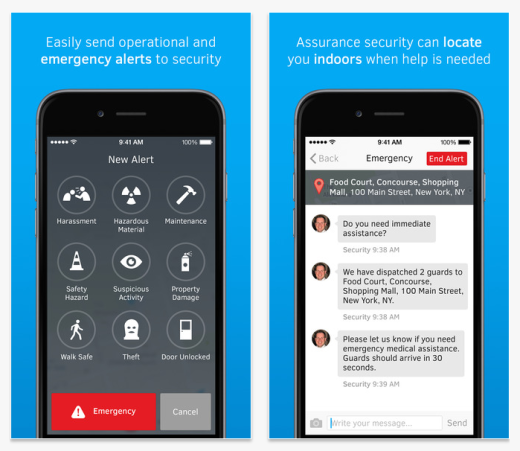

Guardly

Whether you’re traveling overseas on business, in a parking garage with poor cellular coverage or sitting at your desk, Guardly alerts and connects you with your organization’s security operations instantly. Launching Guardly activates its location detection capabilities, transmitting real-time GPS location and indoor positioning within buildings (for select enterprise customers), while providing two-way communication with private security, 911 authorities and safety groups.

Administrators within your organization may also send mobile alerts based on location or user-group, ensuring relevant and reliable messages in case of an emergency.

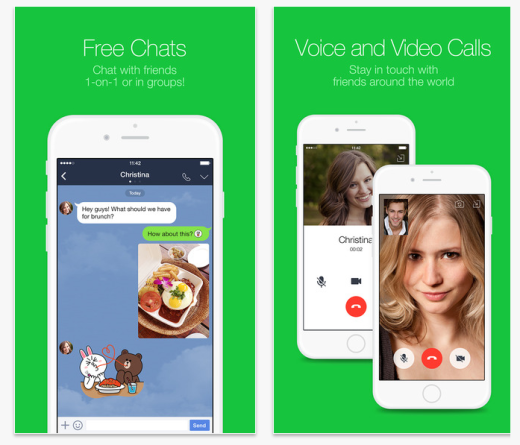

LINE Messenger

Providing free IM and calling through various devices, LINE soon became the world’s fastest-growing social network in the area – exceeding Twitter use within a year. Though widely accepted as a messaging app, LINE has helped thousands of users stay in contact in emergency situations.

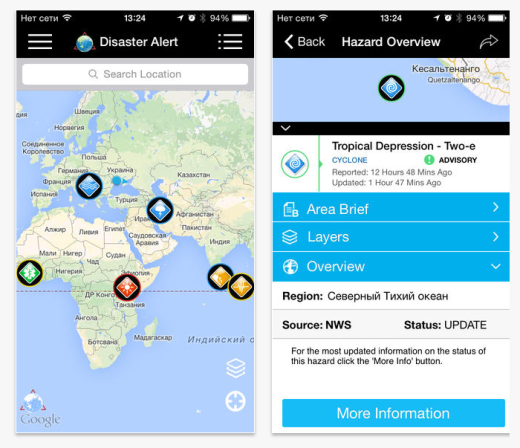

Disaster Alert

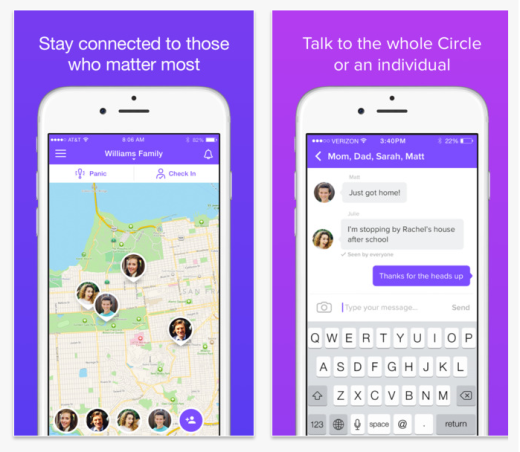

Life360

Available on iPhone, Android and Windows Phones, user can download the app for free. The app notifies your contacts of your location and safety status.

The app also has a panic alert feature you can activate to immediately contact family members via text, email and a voice call to give your location at the moment you need help. There are also options for regular feature phones. For family members without a phone, there is an additional GPS device that can be provided for a fee.

SirenGPS

Red Panic Button

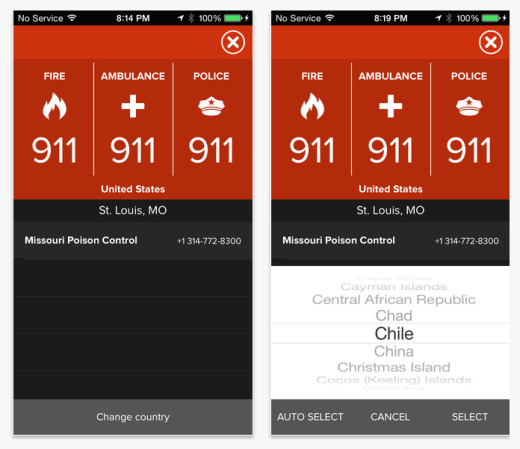

ICE: In Case of Emergency

The app is currently available in 13 languages allowing users to switch between them in case an emergency arises while you are traveling.

While no tool is perfect for all disaster situations, and we hope no one ever has to use them, we also hope that you can find some solace in knowing there are multiple apps out there just in case.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen