... ALIAS THE ECOLOGICAL FOOTPRINT

The ecological footprint measures human demand on nature, i.e., the quantity of nature it takes to support people or an economy. It tracks this demand through an ecological accounting system. The accounts contrast the biologically productive area people use for their consumption to the biologically productive area available within a region or the world (biocapacity, the productive area that can regenerate what people demand from nature). In short, it is a measure of human impact on Earth's ecosystem and reveals the dependence of the human economy on natural capital.

Footprint and biocapacity can be compared at the individual, regional, national or global scale. Both footprint and biocapacity change every year with number of people, per person consumption, efficiency of production, and productivity of ecosystems. At a global scale, footprint assessments show how big humanity's demand is compared to what planet Earth can renew. Since 2003, Global Footprint Network has calculated the ecological footprint from UN data sources for the world as a whole and for over 200 nations (known as the National Footprint Accounts). Every year the calculations are updated with the newest data. The time series are recalculated with every update since UN statistics also change historical data sets. As shown in Lin et al (2018)[2] the time trends for countries and the world have stayed consistent despite data updates. Also, a recent study by the Swiss Ministry of Environment independently recalculated the Swiss trends and reproduced them within 1-4% for the time period that they studied (1996-2015)[3]. Global Footprint Network estimates that, as of 2014, humanity has been using natural capital 1.7 times as fast as Earth can renew it.[4][2][5] This means humanity's ecological footprint corresponds to 1.7 planet Earths.

Ecological footprint analysis is widely used around the Earth in support of sustainability assessments.[6] It enables people to measure and manage the use of resources throughout the economy and explore the sustainability of individual lifestyles, goods and services, organizations, industry sectors, neighborhoods, cities, regions and nations.[7] Since 2006, a first set of ecological footprint standards exist that detail both communication and calculation procedures. The latest version are the updated standards from 2009.[8]

Footprint measurements and methodology[edit]

For 2014, Global Footprint Network estimated humanity's ecological footprint as 1.7 planet Earths. This means that, according to their calculations, humanity's demands were 1.7 times faster than what the planet's ecosystems renewed.[2][9]

Ecological footprints can be calculated at any scale: for an activity, a person, a community, a city, a town, a region, a nation, or humanity as a whole. Cities, due to their population concentration, have large ecological footprints and have become ground zero for footprint reduction.[10]

The ecological footprint accounting method at the national level is described on the web page of Global Footprint Network [11]or in greater detail in academic papers, including Borucke et al.[12]

The National Accounts Review Committee has also published a research agenda on how to improve the accounts.[13]

Overview[edit]

The first academic publication about ecological footprints was by William Rees in 1992.[14] The ecological footprint concept and calculation method was developed as the PhD dissertation of Mathis Wackernagel, under Rees' supervision at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, from 1990–1994.[15] Originally, Wackernagel and Rees called the concept "appropriated carrying capacity".[16] To make the idea more accessible, Rees came up with the term "ecological footprint", inspired by a computer technician who praised his new computer's "small footprint on the desk".[17] In early 1996, Wackernagel and Rees published the book Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth with illustrations by Phil Testemale.[18]

Footprint values at the end of a survey are categorized for Carbon, Food, Housing, and Goods and Services as well as the total footprint number of Earths needed to sustain the world's population at that level of consumption. This approach can also be applied to an activity such as the manufacturing of a product or driving of a car. This resource accounting is similar to life-cycle analysis wherein the consumption of energy, biomass (food, fiber), building material, water and other resources are converted into a normalized measure of land area called global hectares (gha).

The focus of Ecological Footprint accounting is biological resources. Rather than non-renewable resources like oil or minerals, it is the biological resources that are the materially most limiting resources for the human enterprise. For instance, while the amount of fossil fuel still underground is limited, even more limiting is the biosphere’s ability to cope with the CO2 emitted when burning it. This ability is one of the competing uses of the planet’s biocapacity. Similarly, minerals are limited by the energy available to extract them from the lithosphere and concentrate them. The limits of ecosystems' ability to renew biomass is given by factors such as water availability, climate, soil fertility, solar energy, technology and management practices. This capacity to renew, driven by photosynthesis, is called biocapacity.

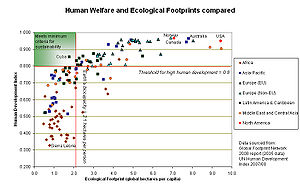

Per capita ecological footprint (EF), or ecological footprint analysis (EFA), is a means of comparing consumption and lifestyles, and checking this against biocapacity - nature's ability to provide for this consumption. The tool can inform policy by examining to what extent a nation uses more (or less) than is available within its territory, or to what extent the nation's lifestyle would be replicable worldwide. The footprint can also be a useful tool to educate people about carrying capacity and overconsumption, with the aim of altering personal behavior. Ecological footprints may be used to argue that many current lifestyles are not sustainable. Such a global comparison also clearly shows the inequalities of resource use on this planet at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

In 2007, the average biologically productive area per person worldwide was approximately 1.8 global hectares (gha) per capita. The U.S. footprint per capita was 9.0 gha, and that of Switzerland was 5.6 gha, while China's was 1.8 gha.[19][20] The WWF claims that the human footprint has exceeded the biocapacity (the available supply of natural resources) of the planet by 20%.[21] Wackernagel and Rees originally estimated that the available biological capacity for the 6 billion people on Earth at that time was about 1.3 hectares per person, which is smaller than the 1.8 global hectares published for 2006, because the initial studies neither used global hectares nor included bioproductive marine areas.[18]

A number of NGOs offer ecological footprint calculators (see Footprint Calculator, below).

Global trends in humanity's ecological footprint[edit]

According to the 2018 edition of the National Footprint Accounts, humanity’s total ecological footprint has exhibited an increasing trend since 1961, growing an average of 2.1% per year (SD= 1.9)[2]. Humanity’s ecological footprint was 7.0 billion gha in 1961 and increased to 20.6 billion gha in 2014[2]. The world-average ecological footprint in 2014 was 2.8 global hectares per person[2]. The carbon footprint is the fastest growing part of the ecological footprint and accounts currently for about 60% of humanity’s total ecological footprint[2].

The Earth’s biocapacity has not increased at the same rate as the ecological footprint. The increase of biocapacity averaged at only 0.5% per year (SD = 0.7)[2]. Because of agricultural intensification, biocapacity was at 9.6 billion gha in 1961 and grew to 12.2 billion gha in 2014[2].

Therefore, the Earth has been in ecological overshoot (where humanity is using more resources and generating waste at a pace that the ecosystem can’t renew) since the 1970’s[2]. In 2018, Earth Overshoot Day, the date where humanity has used more from nature than the planet can renew in the entire year, was estimated to be August 1[22]. Now more than 85% of humanity lives in countries that run an ecological deficit[23]. This means their ecological footprint for consumption exceeds the biocapacity of that country.

Studies in the United Kingdom[edit]

The UK's average ecological footprint is 5.45 global hectares per capita (gha) with variations between regions ranging from 4.80 gha (Wales) to 5.56 gha (East England).[20]

Two recent studies[citation needed] have examined relatively low-impact small communities. BedZED, a 96-home mixed-income housing development in South London, was designed by Bill Dunster Architects and sustainability consultants BioRegional for the Peabody Trust. Despite being populated by relatively "mainstream" home-buyers, BedZED was found to have a footprint of 3.20 gha due to on-site renewable energy production, energy-efficient architecture, and an extensive green lifestyles program that included on-site London's first carsharing club. The report did not measure the added footprint of the 15,000 visitors who have toured BedZED since its completion in 2002. Findhorn Ecovillage, a rural intentional community in Moray, Scotland, had a total footprint of 2.56 gha, including both the many guests and visitors who travel to the community to undertake residential courses there and the nearby campus of Cluny Hill College. However, the residents alone have a footprint of 2.71 gha, a little over half the UK national average and one of the lowest ecological footprints of any community measured so far in the industrialized world.[24][25] Keveral Farm, an organic farming community in Cornwall, was found to have a footprint of 2.4 gha, though with substantial differences in footprints among community members.[26]

Ecological footprint at the individual level[edit]

In a 2012 study of consumers acting "green" vs. "brown" (where green people are «expected to have significantly lower ecological impact than “brown” consumers»), the conclusion was "the research found no significant difference between the carbon footprints of green and brown consumers".[27][28] A 2013 study concluded the same.[29][30]

A 2017 study published in Environmental Research Letters posited that the most significant way individuals could reduce their own carbon footprint is to have fewer children, followed by living without a vehicle, forgoing air travel and adopting a plant-based diet.[31] The 2017 World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice, co-signed by over 15,000 scientists around the globe, urges human beings to "re-examine and change our individual behaviors, including limiting our own reproduction (ideally to replacement level at most) and drastically diminishing our per capita consumption of fossil fuels, meat, and other resources."[32] According to a 2018 study published in Science, avoiding animal products altogether, including meat and dairy, is the most significant way individuals can reduce their overall ecological impact on earth, meaning "not just greenhouse gases, but global acidification, eutrophication, land use and water use".[33]

Reviews and critiques[edit]

Early criticism was published by van den Bergh and Verbruggen in 1999,[34] which was updated in 2014.[35] Another criticism was published in 2008.[36] A more complete review commissioned by the Directorate-General for the Environment (European Commission) was published in June 2008. The review found Ecological Footprint "a useful indicator for assessing progress on the EU’s Resource Strategy" the authors noted that Ecological Footprint analysis was unique "in its ability to relate resource use to the concept of carrying capacity." The review noted that further improvements in data quality, methodologies and assumptions were needed.[37]

A recent critique of the concept is due to Blomqvist et al., 2013a,[38] with a reply from Rees and Wackernagel, 2013,[39] and a rejoinder by Blomqvist et al., 2013b.[40]

An additional strand of critique is due to Giampietro and Saltelli (2014a),[41] with a reply from Goldfinger et al., 2014,[42] a rejoinder by Giampietro and Saltelli (2014a),[43] and additional comments from van den Bergh and Grazi (2015).[44]

A number of countries have engaged in research collaborations to test the validity of the method. This includes Switzerland, Germany, United Arab Emirates, and Belgium.[45]

Grazi et al. (2007) have performed a systematic comparison of the ecological footprint method with spatial welfare analysis that includes environmental externalities, agglomeration effects and trade advantages.[46] They find that the two methods can lead to very distinct, and even opposite, rankings of different spatial patterns of economic activity. However this should not be surprising, since the two methods address different research questions.

Newman (2006) has argued that the ecological footprint concept may have an anti-urban bias, as it does not consider the opportunities created by urban growth.[47]Calculating the ecological footprint for densely populated areas, such as a city or small country with a comparatively large population — e.g. New York and Singapore respectively — may lead to the perception of these populations as "parasitic". This is because these communities have little intrinsic biocapacity, and instead must rely upon large hinterlands. Critics argue that this is a dubious characterization since mechanized rural farmers in developed nations may easily consume more resources than urban inhabitants, due to transportation requirements and the unavailability of economies of scale. Furthermore, such moral conclusions seem to be an argument for autarky. Some even take this train of thought a step further, claiming that the Footprint denies the benefits of trade. Therefore, the critics argue that the Footprint can only be applied globally.[48]

The method seems to reward the replacement of original ecosystems with high-productivity agricultural monocultures by assigning a higher biocapacity to such regions. For example, replacing ancient woodlands or tropical forests with monoculture forests or plantations may improve the ecological footprint. Similarly, if organic farmingyields were lower than those of conventional methods, this could result in the former being "penalized" with a larger ecological footprint.[49] Of course, this insight, while valid, stems from the idea of using the footprint as one's only metric. If the use of ecological footprints are complemented with other indicators, such as one for biodiversity, the problem might be solved. Indeed, WWF's Living Planet Report complements the biennial Footprint calculations with the Living Planet Index of biodiversity.[50] Manfred Lenzen and Shauna Murray have created a modified Ecological Footprint that takes biodiversity into account for use in Australia.[51]

Although the ecological footprint model prior to 2008 treated nuclear power in the same manner as coal power,[52] the actual real world effects of the two are radically different. A life cycle analysis centered on the Swedish Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant estimated carbon dioxide emissions at 3.10 g/kW⋅h[53] and 5.05 g/kW⋅h in 2002 for the Torness Nuclear Power Station.[54] This compares to 11 g/kW⋅h for hydroelectric power, 950 g/kW⋅h for installed coal, 900 g/kW⋅h for oil and 600 g/kW⋅h for natural gas generation in the United States in 1999.[55] Figures released by Mark Hertsgaard, however, show that because of the delays in building nuclear plants and the costs involved, investments in energy efficiency and renewable energies have seven times the return on investment of investments in nuclear energy.[56]

The Swedish utility Vattenfall did a study of full life-cycle greenhouse-gas emissions of energy sources the utility uses to produce electricity, namely: Nuclear, Hydro, Coal, Gas, Solar Cell, Peat and Wind. The net result of the study was that nuclear power produced 3.3 grams of carbon dioxide per kW⋅h of produced power. This compares to 400 for natural gas and 700 for coal (according to this study). The study also concluded that nuclear power produced the smallest amount of CO2 of any of their electricity sources.[57]

Claims exist that the problems of nuclear waste do not come anywhere close to approaching the problems of fossil fuel waste.[58][59] A 2004 article from the BBC states: "The World Health Organization (WHO) says 3 million people are killed worldwide by outdoor air pollution annually from vehicles and industrial emissions, and 1.6 million indoors through using solid fuel."[60] In the U.S. alone, fossil fuel waste kills 20,000 people each year.[61] A coal power plant releases 100 times as much radiation as a nuclear power plant of the same wattage.[62] It is estimated that during 1982, US coal burning released 155 times as much radioactivity into the atmosphere as the Three Mile Island incident.[63] In addition, fossil fuel waste causes global warming, which leads to increased deaths from hurricanes, flooding, and other weather events. The World Nuclear Association provides a comparison of deaths due to accidents among different forms of energy production. In their comparison, deaths per TW-yr of electricity produced (in UK and USA) from 1970 to 1992 are quoted as 885 for hydropower, 342 for coal, 85 for natural gas, and 8 for nuclear.[64]

The Western Australian government State of the Environment Report included an Ecological Footprint measure for the average Western Australian seven times the average footprint per person on the planet in 2007, a total of about 15 hectares.[65]

Footprint by country[edit]

The world-average ecological footprint in 2013 was 2.8 global hectares per person.[2] The average per country ranges from over 10 to under 1 global hectares per person. There is also a high variation within countries, based on individual lifestyle and economic possibilities.[66]

The GHG footprint or the more narrow carbon footprint are a component of the ecological footprint. Often, when only the carbon footprint is reported, it is expressed in weight of CO2 (or CO2e representing GHG warming potential (GGWP)), but it can also be expressed in land areas like ecological footprints. Both can be applied to products, people or whole societies.[67]

Implications[edit]

###########

Ślad ekologiczny – wskaźnik umożliwiający oszacowanie zużycia zasobów naturalnych w stosunku do możliwości ich odtworzenia przez Ziemię. Stanowi podstawę analizy zapotrzebowania człowieka na zasoby naturalne biosfery[1]. Porównywana jest ludzka konsumpcja zasobów naturalnych ze zdolnością planety Ziemi do ich regeneracji. Ślad ekologiczny to szacowana liczba hektarów powierzchni lądu i morza potrzebna do rekompensacji zasobów zużytych na konsumpcję i absorpcję odpadów. Ślad mierzony jest w globalnych hektarach (gha) na osobę.

Przyczyny

Europejska Agencja Środowiska wymienia eksploatację ziemi, wzorce konsumpcyjne i modele handlowe jako największe zagrożenia przyrodnicze w Europie. Obecnie największym wyzwaniem są zanieczyszczenia ze źródeł rozproszonych[2].

Ślad ekologiczny Polski

Według raportu WWF Europa 2007, mimo że wszystkie kraje Unii Europejskiej pogłębiają ekologiczny deficyt Ziemi, Polska zajmuje 20. pozycję z 24 analizowanych państw UE. Mniejszy ślad ekologiczny zostawiają tylko Bułgaria, Słowacja, Łotwa i Rumunia[3].

Mimo że Polacy nadal eksploatują prawie 2 razy więcej niż wynoszą zasoby naturalne kraju, od 1990 r. udało się zmniejszyć deficyt ekologiczny z 3,83 globalnych ha na mieszkańca do 3,3 gha na mieszkańca[1].

#######

Unter dem ökologischen Fußabdruck (auch englisch Ecological Footprint)[1][2] wird die biologisch produktive Fläche auf der Erde verstanden, die notwendig ist, um den Lebensstil und Lebensstandard eines Menschen (unter den heutigen Produktionsbedingungen) dauerhaft zu ermöglichen. Er wird als Nachhaltigkeitsindikator bezeichnet. Das schließt Flächen ein, die zur Produktion von Kleidung und Nahrung oder zur Bereitstellung von Energie benötigt werden, aber z. B. auch zur Entsorgung von Müll oder zum Binden des durch menschliche Aktivitäten freigesetzten Kohlenstoffdioxids. Der Fußabdruck kann dann mit der Biokapazität der Welt oder der Region verglichen werden, also der biologisch produktiven Fläche, die vorhanden ist.

Das Konzept wurde 1994 von Mathis Wackernagel und William Rees entwickelt. 2003 wurde von Wackernagel das Global Footprint Network gegründet, das u. a. von der Nobelpreisträgerin Wangari Maathai, dem Gründer des Worldwatch Institute Lester R. Brown und Ernst Ulrich von Weizsäcker unterstützt wird.

Der ökologische Fußabdruck wird häufig verwendet, um im Zusammenhang mit dem Konzept der Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung auf gesellschaftliche und individuelle Nachhaltigkeitsdefizite hinzuweisen – abhängig davon, ob ein Mensch seine ökologische Reserve in ein Ökodefizit verwandelt.

Maßeinheit[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Die Fruchtbarkeit von Böden auf der Erde ist nicht gleichverteilt. Berge und Wüsten sind naturgemäß weniger fruchtbar als Wiesen oder bewirtschaftete Äcker. Daher würde der normale Hektar eine falsche Wahrnehmung vermitteln. Um den ökologischen Fußabdruck von unterschiedlichen Ländern oder diversen anderen Gebieten miteinander vergleichen zu können, werden die Werte in „Globalen Hektar“ pro Person und Jahr angegeben. Die Einheit trägt meistens die Abkürzung „gha“. Der Globale Hektar entspricht einem Hektar mit weltweit durchschnittlicher biologischer Produktivität.[2]

Methodik[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Das Global Footprint Network legt großen Wert auf die Transparenz seiner Methodik, die in einer Vielzahl von Veröffentlichungen dargelegt und wissenschaftlich abgesichert wird.[3]

Dem Instrument des ökologischen Fußabdrucks liegt eine Frage zugrunde: „Wie viel biologische Kapazität des Planeten wird von einer gegebenen menschlichen Aktivität oder Bevölkerungsgruppe in Anspruch genommen?“[4] Die Methodik setzt zwei Flächen zueinander in Beziehung: Den für einen Menschen durchschnittlich verfügbaren Land- und Wasserflächen (Biokapazität) werden diejenigen Land- und Wasserflächen gegenübergestellt, die in Anspruch genommen werden, um den Bedarf dieses Menschen zu produzieren und den dabei erzeugten Abfall aufzunehmen (der ökologische Fußabdruck). Allerdings beschränkt sich der ökologische Fußabdruck auf biologisch produktive Land- und Wasserflächen, die in die Kategorien Ackerland, Weideland, für Fischerei genutzte Meeresflächen und Binnenwasserflächen sowie Wald eingeteilt werden. Nicht biologisch nutzbare Flächen (bebaute Flächen, aber auch Wüsten und Hochgebirge) gelten als neutral.

Der methodische Erfolg des ökologischen Fußabdrucks beruht darauf, mit Hilfe von Produktivitätsfaktoren diese Flächen umzurechnen in Globale Hektar. Damit kann man sich auf einen durchschnittlich produktiven „Standard-Hektar“ als gemeinsame Maßeinheit beziehen, um weltweit sehr unterschiedliche Flächen miteinander vergleichen zu können. Zudem konnten auf dieser Basis Zahlen bis 1960 zurückgerechnet werden, obwohl der ökologische Fußabdruck erst 1994 „erfunden“ wurde. Die Methodik wurde seitdem noch verfeinert, ohne das Grundkonzept zu verändern.

Der Schwerpunkt des ökologischen Fußabdrucks liegt auf biologischen Ressourcen. Anstelle von nicht erneuerbaren Ressourcen wie Öl oder Mineralien sind es die biologischen Ressourcen, die die materiellen Möglichkeiten der Menschheit am meisten einschränken. Zum Beispiel ist die Menge an fossilen Brennstoffen, die sich immer noch im Untergrund befindet, begrenzt; aber die Fähigkeit der Biosphäre, mit dem bei der Verbrennung emittierten CO2 Gase umzugehen, ist noch begrenzender. Diese Nachfrage nach Biokapazität konkurriert mit anderen Nutzungen der Biokapazität des Planeten. In ähnlicher Weise sind Mineralien durch die zur Verfügung stehende Energie begrenzt; also die Energie, die notwendig ist um sie aus der Lithosphäre zu extrahieren und zu konzentrieren. Diese Energie ist auch limitiert durch die verfügbare Biokapazität. Die Möglichkeiten der Ökosysteme, Biomasse zu erneuern, sind begrenzt durch Faktoren wie Wasserverfügbarkeit, Klima, Bodenfruchtbarkeit, Sonneneinstrahlung, Technologie und Managementpraktiken. Diese durch Photosynthese getriebene Erneuerungsfähigkeit wird als Biokapazität bezeichnet.)[5]

Der ökologische Fußabdruck macht von vornherein eine Reihe von methodischen Einschränkungen, die Einfluss auf seine Aussagekraft haben:

- Kohlendioxid als wichtigstes Treibhausgas: Anthropogenes CO2 entsteht hauptsächlich bei der Verbrennung fossiler Brennstoffe. Der ökologische Fußabdruck setzt für diese Emissionen einen Flächenverbrauch in Form von Wald an, der nötig wäre, um das erzeugte CO2 biologisch zu binden. Dabei wird vorhandener Wald unterstellt, der einen jährlichen Zuwachs an Biomasse hat (als lebende Pflanze oder verrottender Humus), die nicht entnommen wird. Dieser Flächenanteil ist für den hohen ökologischen Fußabdruck der meisten Industrieländer verantwortlich. Allerdings wird derjenige Anteil CO2 abgezogen, der von den Ozeanen absorbiert wird, die als natürliches Depot für CO2 angesehen werden. Hierbei wird nicht berücksichtigt, dass die Versauerung der Weltmeere durch CO2 eine der Planetarischen Grenzen darstellt.

- Abfälle werden in drei Kategorien eingeteilt: (1) Biologisch abbaubare Abfälle, die als „neutral“ nicht in die Rechnung eingehen (bzw. im Fußabdruck der entsprechenden produzierenden Fläche enthalten sind). (2) Deponierbare „normale“ Abfälle, die eigentlich mit dem Flächenraum eingehen müssten, der für die langfristige Deponierung notwendig ist. Derzeit wird allerdings nur anthropogenes CO2 einbezogen.[6] (3) Materialien, die nicht durch biologische Prozesse hergestellt oder nicht durch biologische Systeme absorbiert werden (insbesondere Kunststoffe, aber auch toxische und radioaktive Stoffe). Sie haben keinen definierten ökologischen Fußabdruck, für solche Abfälle benötigt man andere Indikatoren. Damit werden letztlich keinerlei Abfälle im umgangssprachlichen Sinne durch den ökologischen Fußabdruck erfasst. Recycling wird nicht explizit erfasst, da es den Fußabdruck „automatisch“ reduziert.

- Nichterneuerbare Ressourcen wie Kupfer, Zinn, Kohle, Erdöl kommen von außerhalb der Biosphäre und haben keinen ökologischen Fußabdruck im Sinne der Methodik. Die „Nebenverbräuche“ der Produktion wie Energieaufwand und anderer Materialverbrauch können berücksichtigt werden. Fossile Energieträger sind ein Sonderfall nichterneuerbarer Ressourcen, da sie zumindest innerhalb des biologischen Kreislaufs stehen, auch wenn sie aus einem anderen Zeitalter stammen. Für sie wird die Fläche angesetzt, die nötig ist, um das freigewordene CO2 biologisch zu binden. Wollte man eine Fläche definieren, die nötig wäre, um fossile Energieträger zu regenerieren, käme man auf Fußabdrücke, die viele hundertmal größer wären als die heute berechneten.[7]

- Frischwasserverbrauch wird nicht betrachtet, da Wasser nur eine biologisch neutrale „Umlaufgröße“ ist und per Saldo weder verbraucht noch erzeugt wird. Ebenso wenig gehen Verluste an Biodiversität ein. Beide Größen gehören jedoch zu den Planetarischen Grenzen.

Bewertung[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Das Konzept des ökologischen Fußabdrucks hat eine Reihe von Stärken und Schwächen, die von den Autoren mit der gleichen Offenheit wie die Methodik erörtert werden.[8][9][10][11]

Zu den Stärken gehören: Das Konzept ist leicht zu visualisieren und zu kommunizieren, ein Globaler Hektar ist sehr anschaulich. Sein starker Reduktionismus ist hilfreich, insbesondere im Bereich der Umweltbildung. Basis ist der Status quo, weder gibt es Spekulationen über zukünftige Technologien, noch Annahmen über „sinnvollen“ Konsum oder „notwendigen“ Lebensstandard. Der Begriff der Tragfähigkeit wird bewusst vermieden. Die Methodik ist 1994 entwickelt worden und seitdem grundsätzlich unverändert geblieben. Alte Zahlen sind mit neuen vergleichbar, Zahlen für vergangene Zeiträume errechenbar.

Dem stehen folgende Schwächen gegenüber: Die Reduktion auf eine Kenngröße ist auch eine elementare Schwäche. Die Autoren geben zu, dass dieses unvollständige Bild durch komplementäre Indikatoren ergänzt werden muss, die „andere wichtige Aspekte von Nachhaltigkeit“ berücksichtigen. Daneben ist der Hektar-Ansatz nicht für alle biologischen Faktoren anwendbar (Wasserverbrauch, Biodiversität). Nichtbiologische Faktoren wie Abfälle, nichterneuerbare Ressourcen oder toxische und andere gefährliche Substanzen finden gar keinen Platz in der Methodik. Die Produktion von CO2 trägt in den meisten Industrieländern mehr als die Hälfte des Fußabdrucks bei. Diese Dominanz eines einzigen Faktors, der ein Stück weit aus der Methodik der biologisch produktiven Flächen herausfällt, ist methodisch problematisch. Der Produktivitätsfaktor ist ebenfalls nicht unproblematisch – intensive und monokulturelle Landwirtschaft hat danach einen kleineren Flächenverbrauch als ökologischer Landbau und schneidet im Fußabdruck besser ab.

Der ökologische Fußabdruck liefert einen Überblick über die Lage sowie Einsichten für einzelne Regionen. Ein ausgewogener ökologischer Fußabdruck ist jedoch nur eine notwendige Mindestbedingung für Nachhaltigkeit und nicht hinreichend. Es besteht die Gefahr der Instrumentalisierung durch Länder oder Organisationen, die nach diesem Kriterium relativ gut abschneiden.

Als Alternative zum ökologischen Fußabdruck nach dem globalen Hektar dient der komplexe und umfangreiche Sustainable Process Index (SPI), mit welchem neben allen Stoff- und Energieflüssen auch sämtliche Emissionen erfasst werden können.

Daten von Kontinenten und Staaten[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

| Region | Bevölkerung* | Ökologischer Fußabdruck** | Biokapazität** | Ökologisches Defizit (<0) oder Reserve (>0) | Bevölkerung* Biokapazität entspricht Ökologischen Fußabdruck*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welt | 7181,7 | 2,87 | 1,71 | 0,6 | 4279 |

| Afrika | 1176,7 | 1,4 | 1,23 | 0,9 | 1133,8 |

| Asien | 4291,3 | 2,32 | 0,77 | 0,3 | 1424,3 |

| Nordamerika | 352,4 | 8,61 | 5,02 | 0,6 | 205,5 |

| Südamerika | 410,0 | 3,01 | 7,48 | 2,5 | 1018,9 |

| Australien und Neuseeland | 27,7 | 8,21 | 14,76 | 1,8 | 49,8 |

| Europa | 736,8 | 4,87 | 3,24 | 0,7 | 490,2 |

| Land | Bevölkerung* | Ökologischer Fußabdruck** | Biokapazität** | Ökologisches Defizit oder Reserve** | Bevölkerung* Biokapazität entspricht Ökologischen Fußabdruck*** |

| Amerika | |||||

| Brasilien | 204,3 | 3,02 | 8,85 | 5,83 | 598,7 |

| Kanada | 35,2 | 8,76 | 16,18 | 7,42 | 65 |

| USA | 317,1 | 8,59 | 3,78 | -4,81 | 142,7 |

| Asien | |||||

| VR China | 1393,6 | 3,59 | 0,93 | -2,66 | 361 |

| Indien | 1279,5 | 1,06 | 0,44 | -0,62 | 531,1 |

| Israel | 7,8 | 5,96 | 0,32 | -5,64 | 0,42 |

| Japan | 126,9 | 4,99 | 0,71 | -4,28 | 18,1 |

| Katar | 2,1 | 12,6 | 1,21 | -11,39 | 0,2 |

| Europa | |||||

| Belgien | 11,15 | 6,89 | 1,13 | - 5,76 | 1,83 |

| Dänemark | 5,6 | 6,11 | 4,57 | - 1,54 | 4,19 |

| Deutschland | 80,57 | 5,46 | 2,25 | - 3,21 | 33,2 |

| Finnland | 5,45 | 6,73 | 13,34 | 6,61 | 10,8 |

| Frankreich | 63,88 | 5,06 | 2,91 | - 2,15 | 36,7 |

| Norwegen | 5,1 | 5,76 | 7,9 | 2,14 | 6,9 |

| Schweden | 9,62 | 6,53 | 10,41 | 3,88 | 15,1 |

| Schweiz | 8,1 | 5,28 | 1,23 | - 4,04 | 1,9 |

| UK | 63,96 | 5,05 | 1,27 | - 3,78 | 16,1 |

* in Millionen

** in globalen Hektaren pro Person (oder gha/Person)

** in globalen Hektaren pro Person (oder gha/Person)

*** Bevölkerung in Millionen, bei der die Biokapazität dem ökologischen Fußabdruck entspricht (Biokapazität / ökologischer Fußabdruck) * Bevölkerung bei gleichbleibender Biokapazität. Bei dieser Bevölkerung könnte der ökologische Fußabdruck von der Biokapazität egalisiert werden. Hier ist nicht berücksichtigt, dass die Biokapazität steigt / fällt, wenn die Bevölkerung abnimmt / zunimmt.

Den größten ökologischen Fußabdruck hatten im Jahr 2013 im Durchschnitt die Einwohner Luxemburgs mit 13,09 gha/Person, die Bewohner Katars mit 12,57 gha/Person und die Bevölkerung von Australien mit 8,8 gha/Person. Den geringsten hatten die Menschen in Burundi mit 0,63 gha/Person, Haiti mit 0,61 gha/Person und Eritrea mit 0,51 gha/Pers.[13]

Die weltweite Inanspruchnahme zur Erfüllung menschlicher Bedürfnisse überschreitet nach Daten des Global Footprint Network und der European Environment Agency derzeit die Kapazität der verfügbaren Flächen um insgesamt 68 %. Danach werden gegenwärtig pro Person 2,87 gha verbraucht, es stehen allerdings lediglich 1,71 gha zur Verfügung. Dabei verteilt sich die Inanspruchnahme der Fläche sehr unterschiedlich auf die verschiedenen Regionen: Europa beispielsweise benötigt 4,87 gha pro Person, kann aber selbst nur 3,24 gha zur Verfügung stellen. Dies bedeutet eine Überbeanspruchung der europäischen Biokapazität um über 50 %. Frankreich beansprucht dabei annähernd das Doppelte, Deutschland knapp das Zweieinhalbfache und Großbritannien fast das Vierfache seiner jeweils vorhandenen Biokapazität. Ähnliche Ungleichgewichte finden sich auch zwischen Stadt und Land.

Ecological Debt Day[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Anhand des ökologischen Fußabdrucks lässt sich das ökologische Defizit berechnen. Der „Ecological Debt Day“ bzw. „Earth Overshoot Day“, der im Deutschen auch als „Ökoschuldentag“ oder „Welterschöpfungstag“ bezeichnet wird, ist eine jährliche Kampagne der Organisation Global Footprint Network. Dieser gibt den Kalendertag jeden Jahres an, ab welchem die von der Menschheit konsumierten Ressourcen die Kapazität der Erde übersteigen, diese zu generieren. Berechnet wird der Ecological Debt Day durch Division der weltweiten Biokapazität, also der während eines Jahres von der Erde produzierten natürlichen Ressourcen, durch den ökologischen Fußabdruck der Menschheit multipliziert mit der Zahl 365, der Anzahl von Tagen im Gregorianischen Kalender. Im Jahr 2017 lag er am 2. August. Der jährliche Trend zeigt eine Vorverlegung zu einem früheren Datum, wobei es jedoch aufgrund der Methodik sowie neuer Erkenntnisse zu einer gewissen Schwankungsbreite kommt.[14][15]